Collier Schorr – Acting Out

That identity can be understood as a kind of social performance, an acting out, is a key assumption of contemporary thought, which takes for granted its essential changeability. But the conflict between this assumption and the perceived continuity of our individual experiences can still be acute. Such complexity is perhaps nowhere more fraught than with the issue of sexual identity, or rather, of gender. While the uncoupling of gender from sex seems to offer a path through the impasse of sexual difference, where the biological signifiers that define a body as male or female (sex) needn’t correspond to its associated cultural constructs (gender), the solution is perhaps not so clear-cut. After all, where does biology end and culture begin? So if it is undoubtedly, and crucially, true that someone might experience their biologically given “sex” as not corresponding to who they are and consequently transition in order to reconcile with their sense of themselves, it is also the case that this opposition of sex and gender defers the difficult question of how those cultural constructs come to be inscribed on and performed by real, living bodies in the first place.

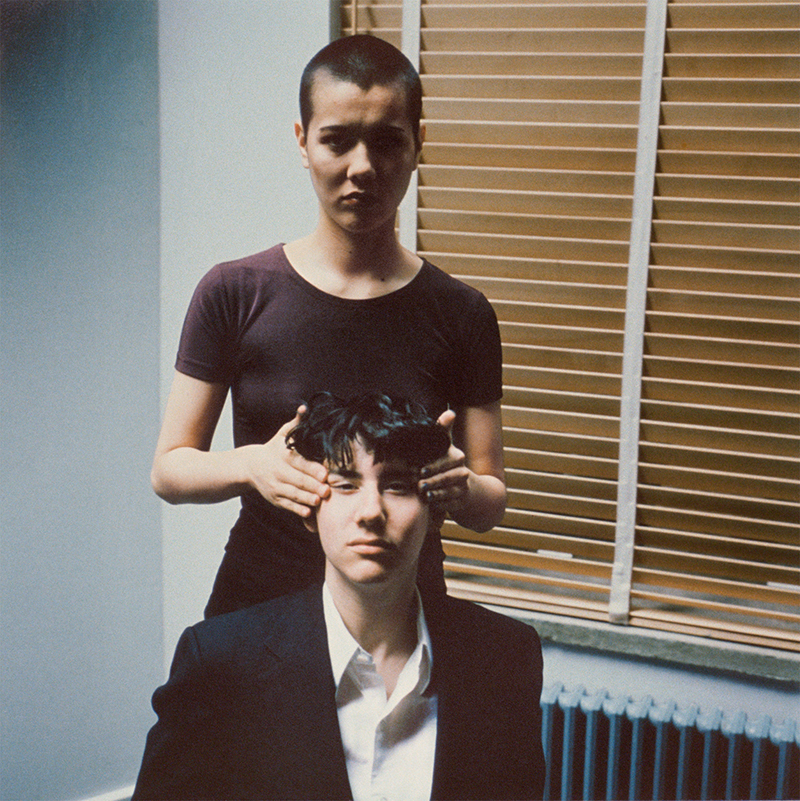

Collier Schorr is an artist who has consistently worked at making visible the protean structure of identity, so that conventional assumptions about its stability, especially with regard to gender, are often provocatively unmade by her pictures. Indeed, it is key to her work that these are pictures, that is, representations of particular individuals who perform – or conspicuously fail to perform – the roles that are expected of them on account of a particularly gendered form. Schorr is by no means limited to a specifically photographic practice; she has freely included collage and other media into her projects, for example. But exploiting the fundamental ambiguity of the photographic image, its capacity to appear at once as a complex of visual (or social) codes and as a “natural” depiction of a subject, gives her work much of its particular charge, because it is precisely such ambiguity that is at stake here, a flickering between what is coded and what is (or at least appears to be) un-coded. In that sense the act of representation is decisively linked to the “acting” self. Schorr resists confining sexual identity to these performed roles alone; the gendered body remains the ground on which such performances are made legible. She suggests instead the multiple roles contained within that frame, locating one within the other, rather than seeking to create a simple binary distinction between them.

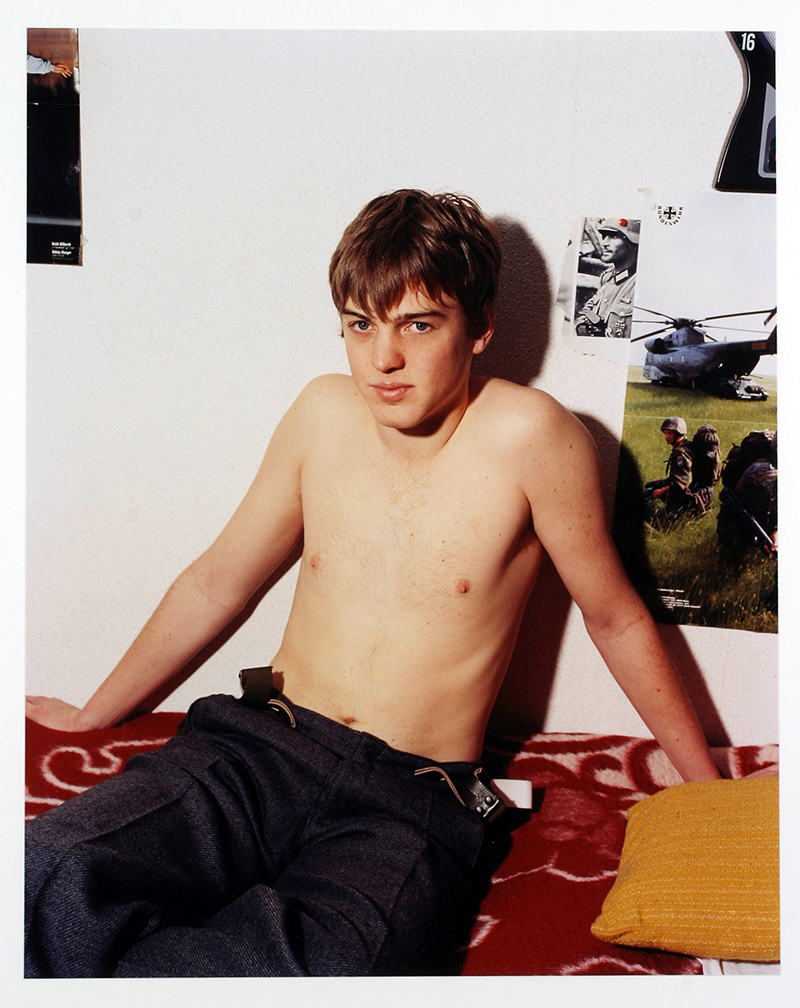

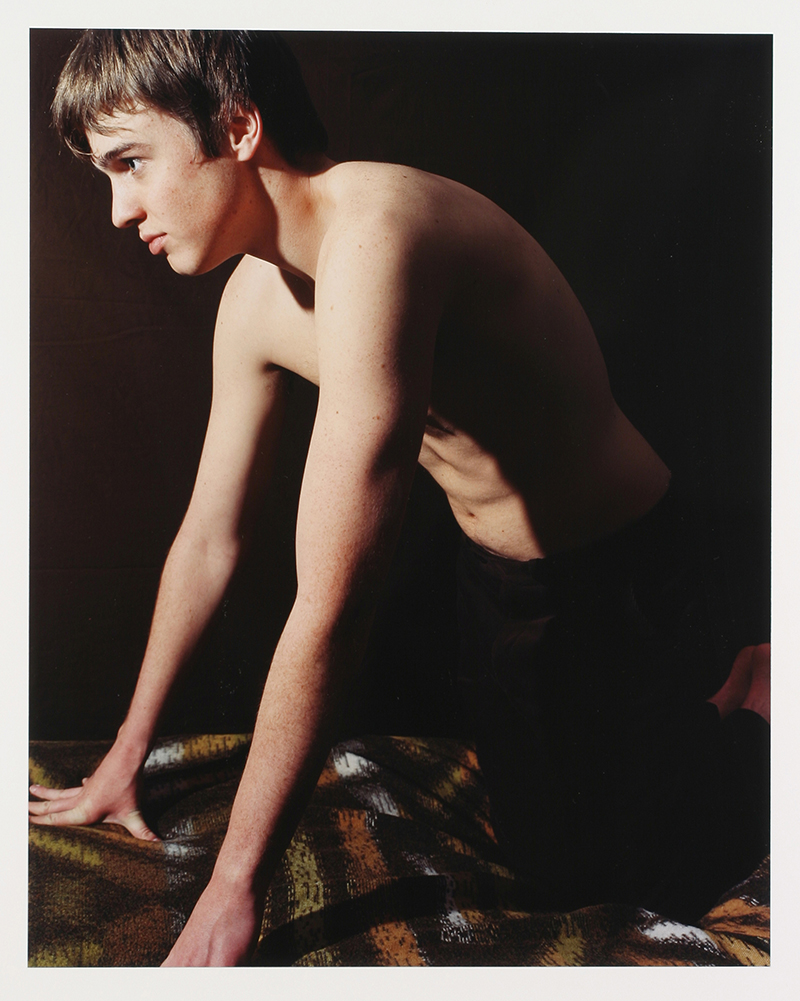

One of Schorr’s most significant works in this vein is her series Jens F., partly inspired by, and in dialogue with, a set of paintings by the American artist Andrew Wyeth that depict his model/ muse, a woman named Helga, in a variety of poses. Schorr’s main subject, however, is a German teenager, the eponymous Jens, who agreed to collaborate on the work. Of course, the Wyeth pictures are not being directly recreated, except with reference to their vocabulary of specific (and telling) poses. It is the role of Helga that is assumed by Jens here, he is – as Helga was – a subject to be looked at. Consequently, the pictures become an experiment in the nature of the gaze, in how the “other” might be seen and represented. Of course, the trope of the gaze has been a staple of recent critical thought, where the implied mastery of the (male) artist/ viewer over the docile body of the female subject is communicated by the structure of the image itself. Seeing becomes possession, dividing the observer from the observed, and it is necessarily women who are seen. This habit is all but inescapable, the dictates of the gaze internalized, even by woman themselves. But Schorr solves the “problem” of the gaze by having the role of the female subject be performed by a young man; in photographing men she is seeing women.

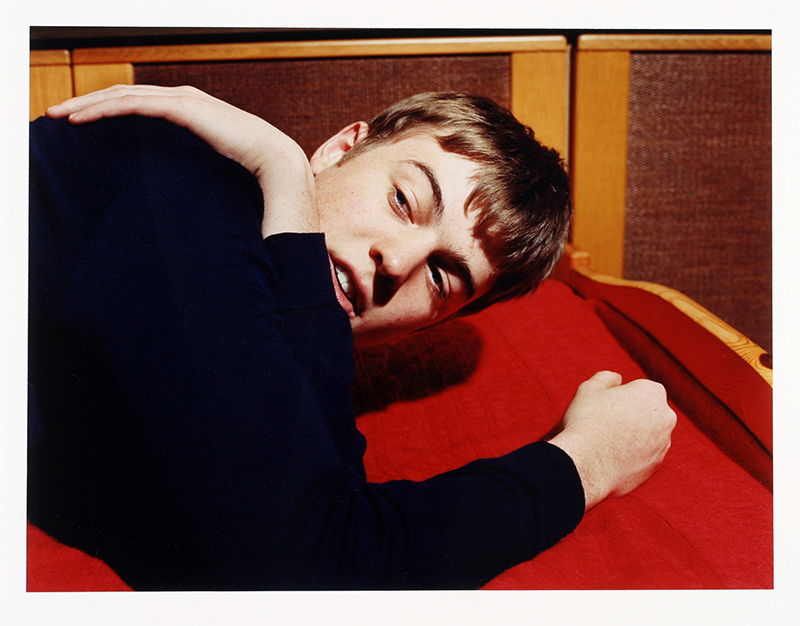

Here it is the expressly male body that performs – embodies – the archetypally “female” role as a visible subject. Schorr is not trying in this way to subvert the ostensible “masculinity” of her subject by drawing attention to or even accentuating the implicitly “feminine” characteristics of how he poses; to do so would assume the normative values of both of these identifications. Instead she suggests a sense of possibility where each state could be contained within the other, as a continuum rather than an opposition, their distinctions superimposed. The collage form of many works in the series, often directly incorporating the source material by Wyeth along with her own photographs, makes the point that the work is explicitly about the representation of bodies, gendered and performing, about how they are seen and how that seeing makes the embodied experience what it is, a social as well as a purely corporeal reality. Similar concerns drive Shorr’s pictures of wrestlers, though in this case the work has a more distinct formal consistency. Using direct flash and a saturated palette, her figures stand out against a dark ground; if nothing else it is the stylised nature of the pictures that separates them from any kind of “documentary” intent and indeed only serves to underscore the intimate charge of the wrestlers’ physical proximity.

As is characteristic, the forthright, in this case somewhat exaggerated masculinity of the wrestlers becomes a way to see into the complex patterns of sexual difference, to visualize a space that contains it without contradiction, even unconsciously, because the wrestlers themselves seem not be aware of the “femaleness” that Schorr finds in their sanctioned performance of male aggression, surely the very quality that drew her interest to begin with. It is under the guise of this aggression that the wrestlers – in Shorr’s vision of them at least – act out a kind of intimacy that would otherwise be unthinkable between men. It is precisely in the evocation of such desire, the struggling bodies, their movement from aggression to submission and back again, that Shorr touches on this putative femaleness, piercing the thin veneer of youthful, reflexive masculinity. It is no coincidence either that this same movement accounts for the intersection of hatred for women and for gay men. But to Shorr the paradox of the gaze is infinitely more tender; the location of sameness in difference must necessarily be a gesture of affirmation. At the same time, she is acutely aware that the value accorded to the roles of men and women in a culture dominated by men are bound to be fundamentally unequal. That these roles appear to be predicated on specific bodies, however constituted, does not preclude that they might still be re-imagined.

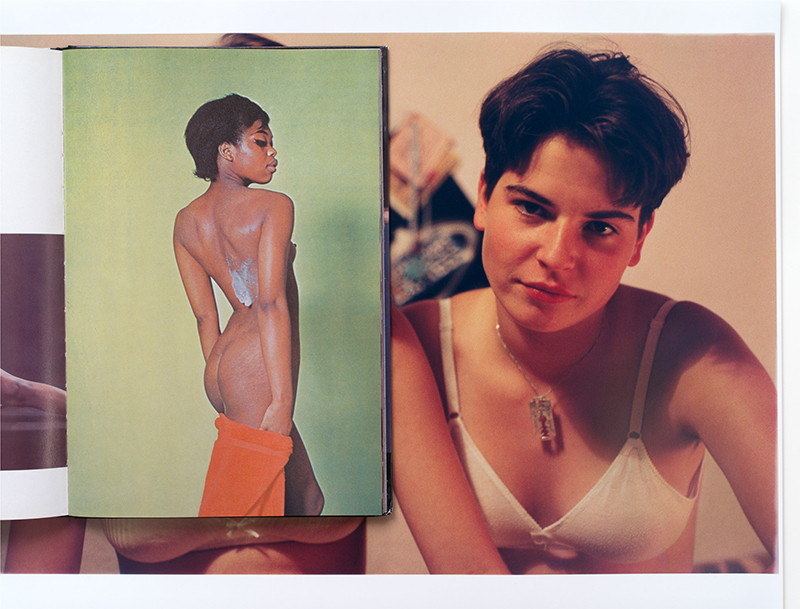

What runs through all of Schorr’s work is a challenge to the formula that assumes men act and women are looked at; in many of her works it is men that take the place of the “female” subject, with everything that this substitution implies. But she has, of course, also photographed women, and with equally challenging results, such as in her recent series, 8 Women, also realised as a publication. The work is in many ways a sort of anthology, given that it includes commissioned fashion photography along with other work referencing the conventions of such images. The combination returns us to a consideration of performance in relation to gender roles. The subjects of these pictures constantly flicker between different positions along a spectrum; the same face, the same gesture can function in the picture as the assertion of both male and female identity, their coexistence suggesting a fundamental ambiguity, but crucially it is one from which the (performing) body itself has not been excluded. At stake here is not the simple matter of men looking like women or vice versa, it is also that men can be seen as women and further, that they can embody that sense of possibility. In Schorr’s work the signifiers of gender – of gendered bodies – are not arbitrary constructions, but an unstable compound of biology and culture, to be written or indeed, unwritten on our living selves.