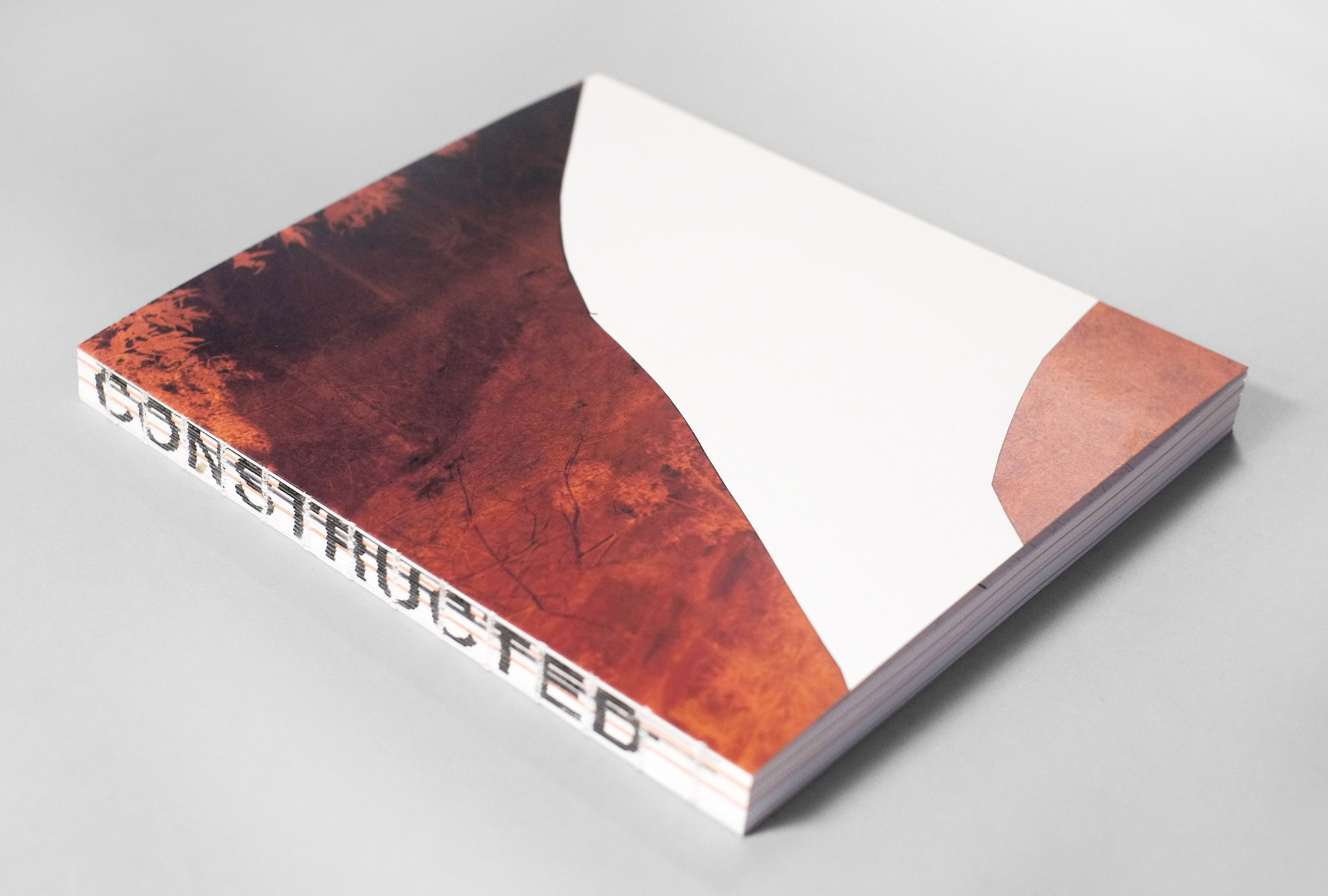

Dafna Talmor – Constructed Landscapes

…where late Cubist works attempted to remove all references to three-dimensional space, Talmor plays with our predisposition to see such space where it doesn’t necessarily exist, creating environments that appear familiar at first glance, but that become increasingly alien and strange the closer you look.

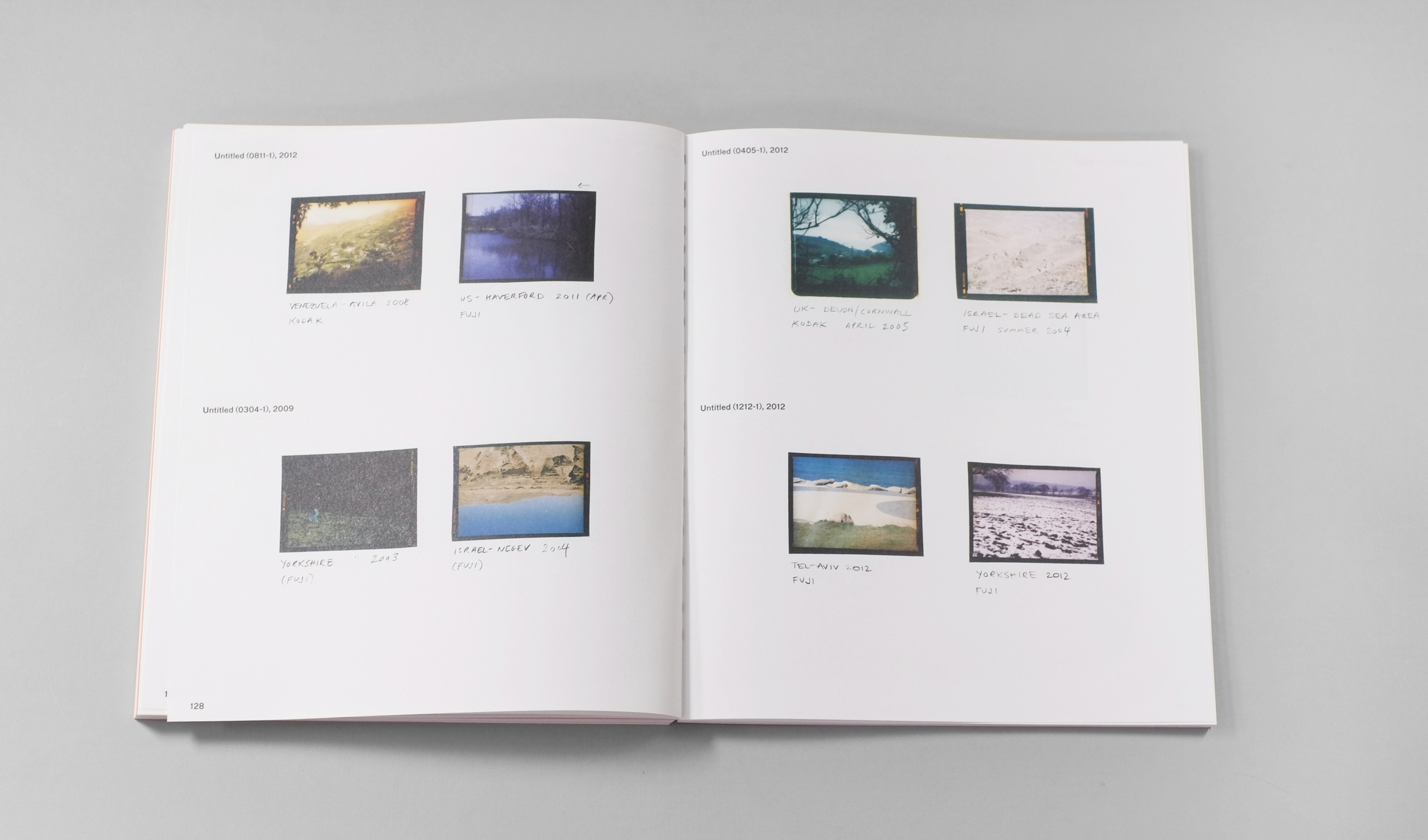

The title of Dafna Talmor’s first book – Constructed Landscapes (published by Fw:Books) – is a tautology. A landscape – whether an image or a physical intervention in an actual environment – is a constructed space by definition. The irony isn’t lost on Talmor, whose creative process involves deconstructing her own landscape photographs, cutting up and recombining multiple negatives to create new hybrid compositions. She began working this way in 2009, driven largely by instinct, and by a sense of dissatisfaction with the photographs that she shot obsessively while travelling. ‘When I came back to the studio and looked at the contact sheets,’ she remarks, ‘I was always disappointed with the images – they weren’t really doing anything very interesting in themselves. But I kept taking pictures.’ The idea that a single image is somehow insufficient is one that is also close to my own heart – particularly when that image fails to capture whatever it was about a site that motivated us to photograph it in the first place.

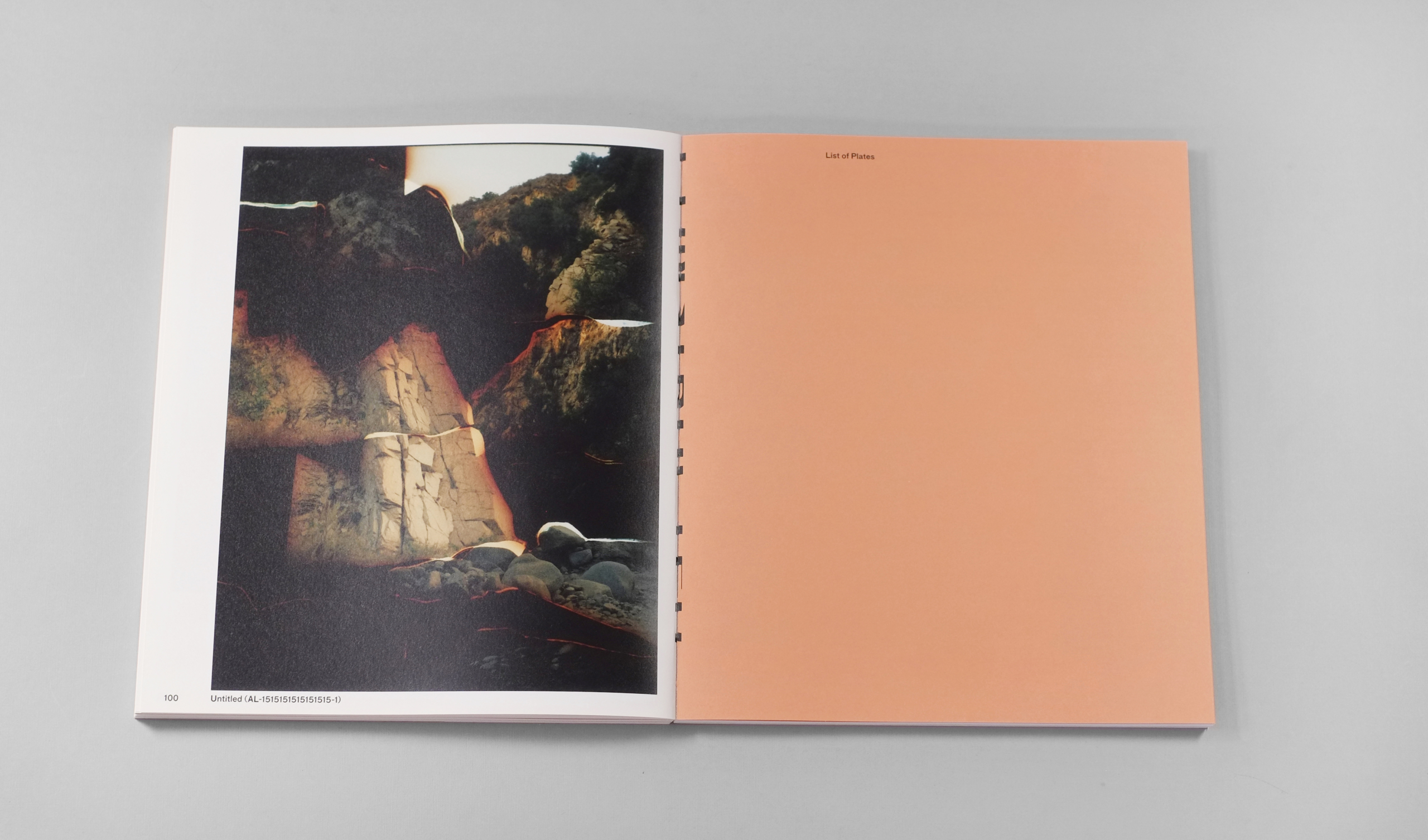

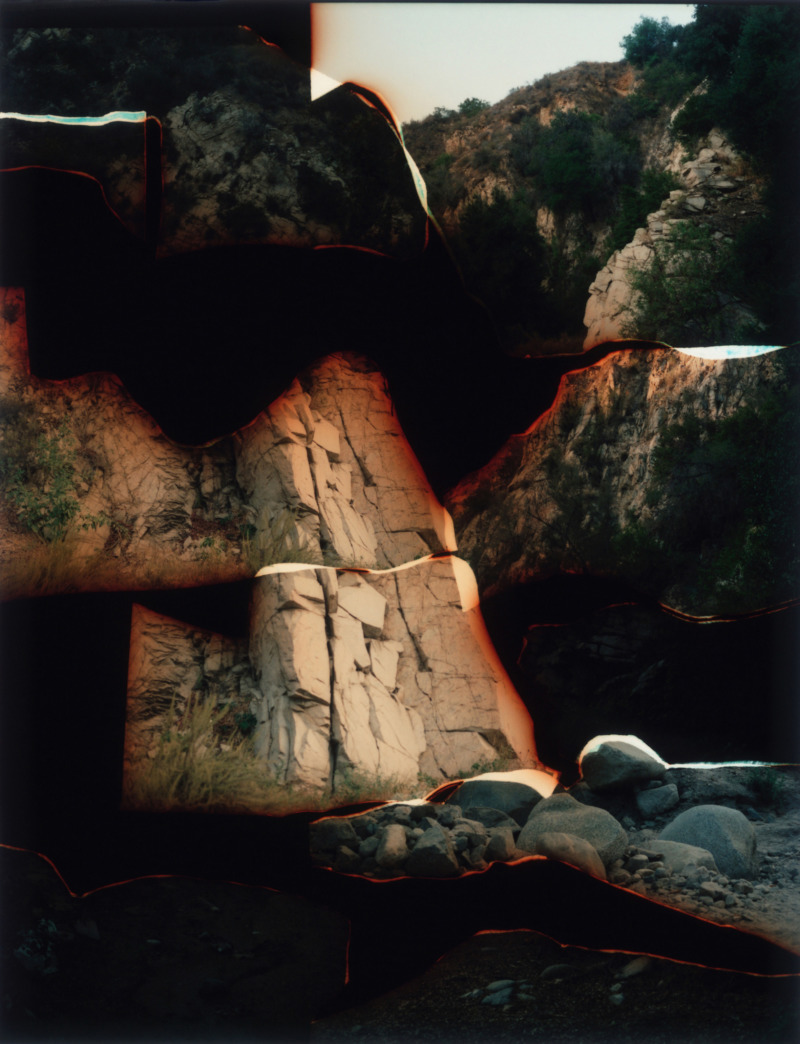

Talmor starts by removing all obvious traces of human intervention from her negatives. She’s well aware that what’s left behind may not necessarily be ‘natural’ at all – many features that look like the result of natural processes often turn out to be artificial. But imposing limitations is an intrinsic part of her practice: ‘I wanted to make sure what I was cutting out wasn’t arbitrary and that there was an internal logic I was adhering to.’ The way that this logic is employed has changed significantly over the years. Her early works, which merge two negatives shot in different locations, often retain the recognisable structure of landscape; a horizon line, a screen of trees framing a foreground, receding layers leading into a deep space. As the process evolved, however, Talmor began to abandon Western pictorial convention in favour of more abstract compositions. Since 2014, she has worked with irregularly shaped segments of negative, separated by black voids. The colour palette has softened and refined too, incorporating rich cobalt blues, greys and ochres and deep orange – abbreviated tones of her preferred elements of water, earth and rock. By her own admission, Talmor struggles to include features like trees and green rolling hills: ‘It’s not that I don’t enjoy those types of landscapes personally, I just find them harder to deal with photographically,’ she remarks.

Structurally, Talmor’s work has strong affinities with the Cubists’ tactic of breaking up and reassembling a single object from multiple viewpoints. Visually and conceptually, however, the two are quite different. Composed out of multiple negatives shot from different positions in the same location, many of Talmor’s more recent works alternate between flatness and depth, retaining ghostly traces of the original landscape. And where late Cubist works attempted to remove all references to three-dimensional space, Talmor plays with our predisposition to see such space where it doesn’t necessarily exist, creating environments that appear familiar at first glance, but that become increasingly alien and strange the closer you look.

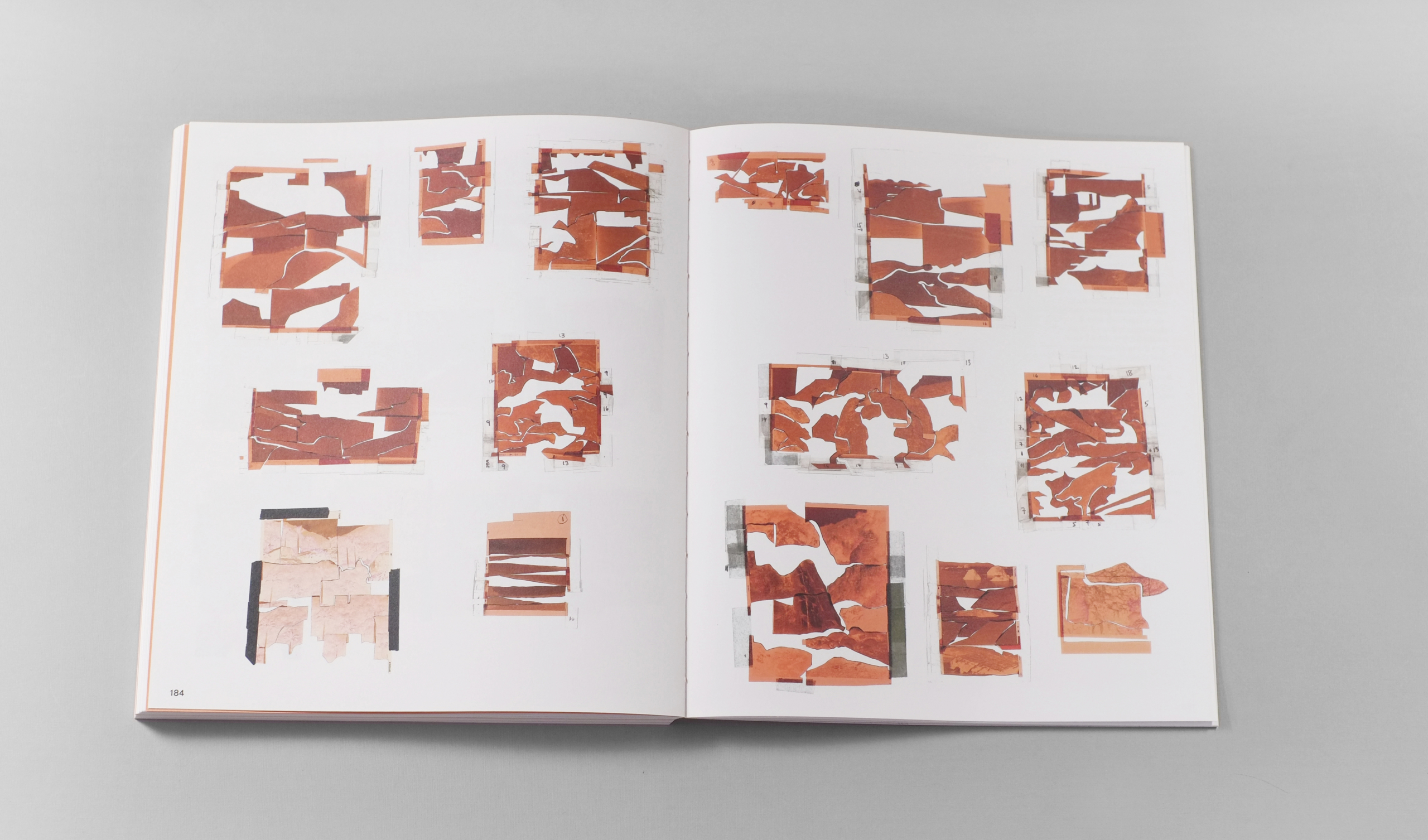

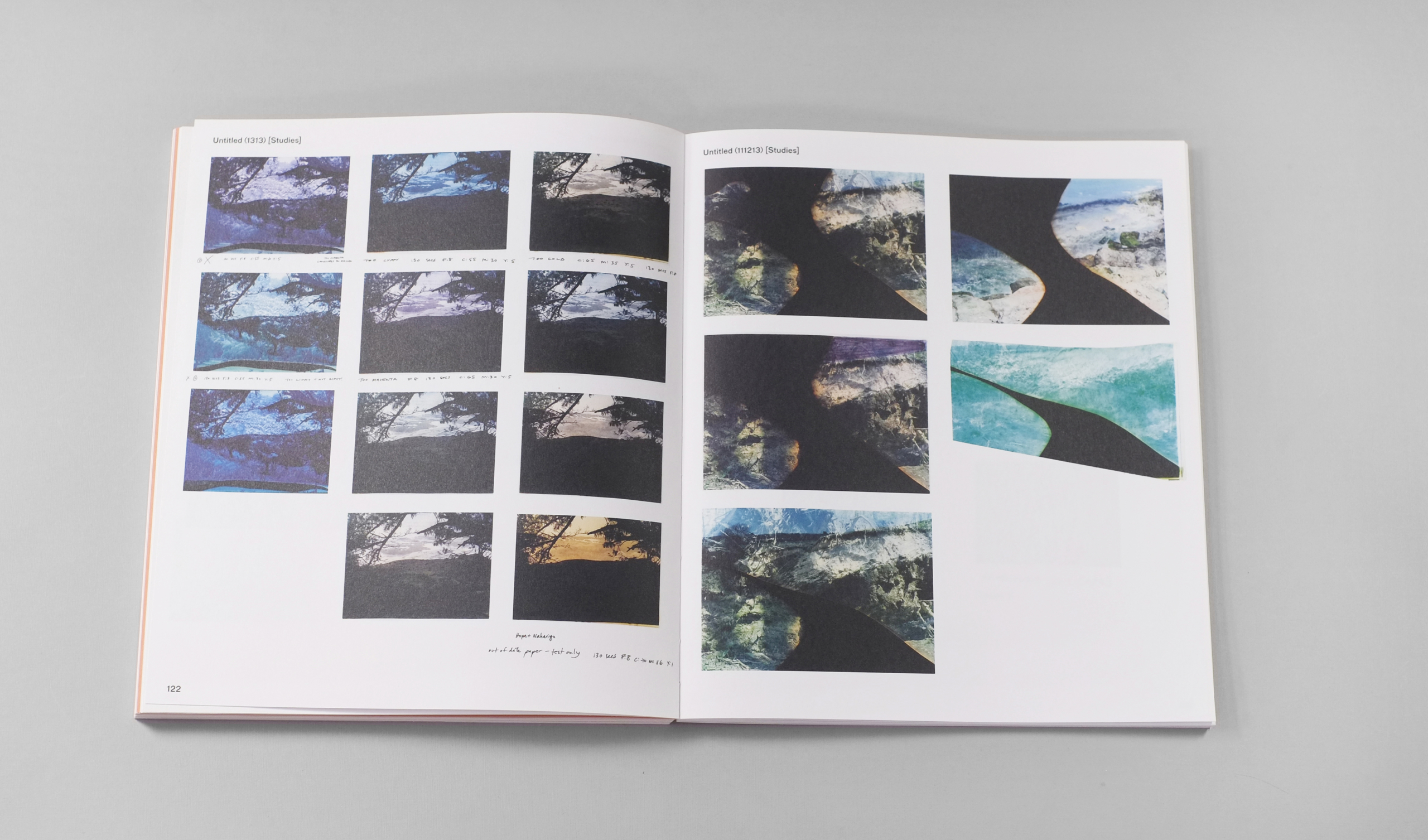

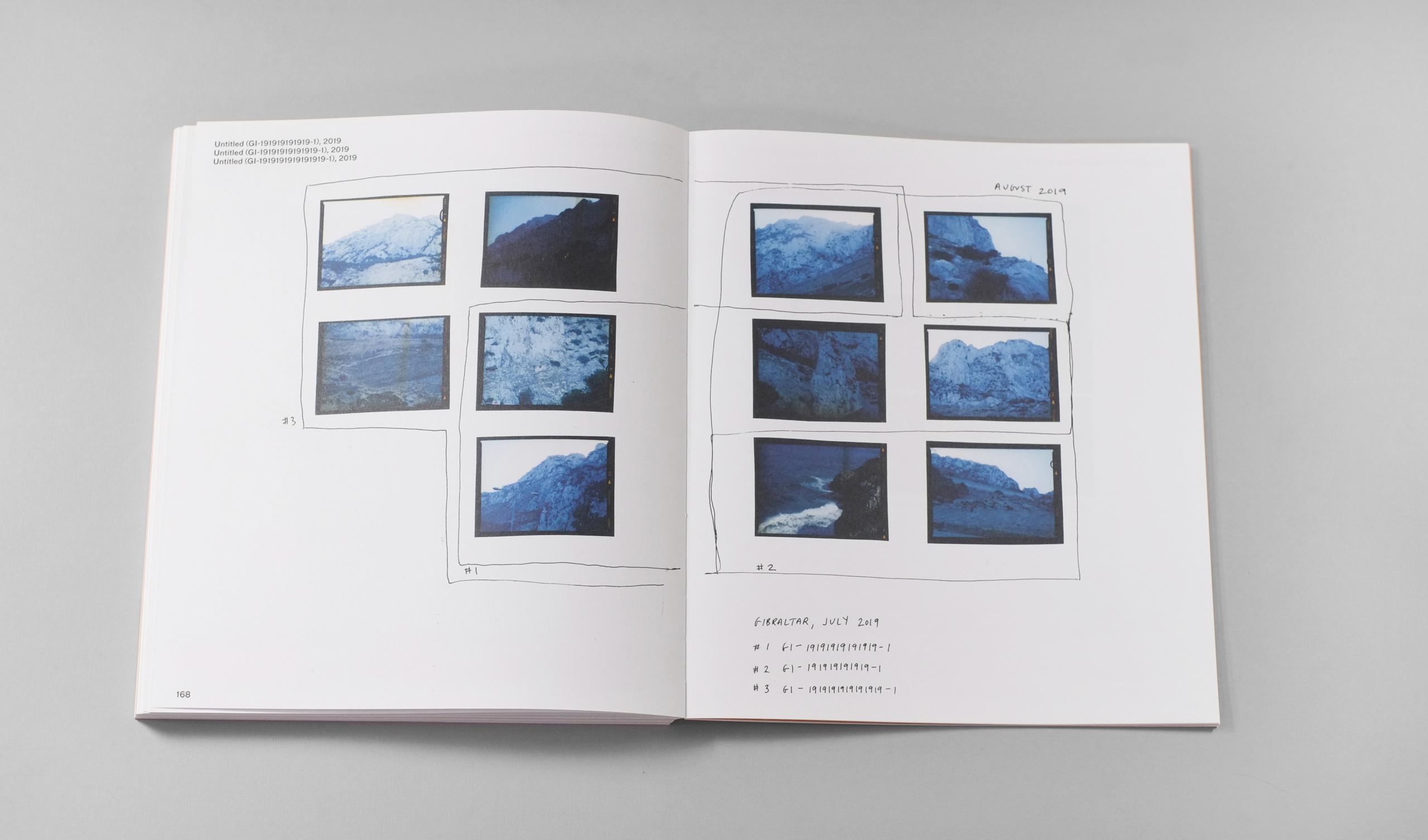

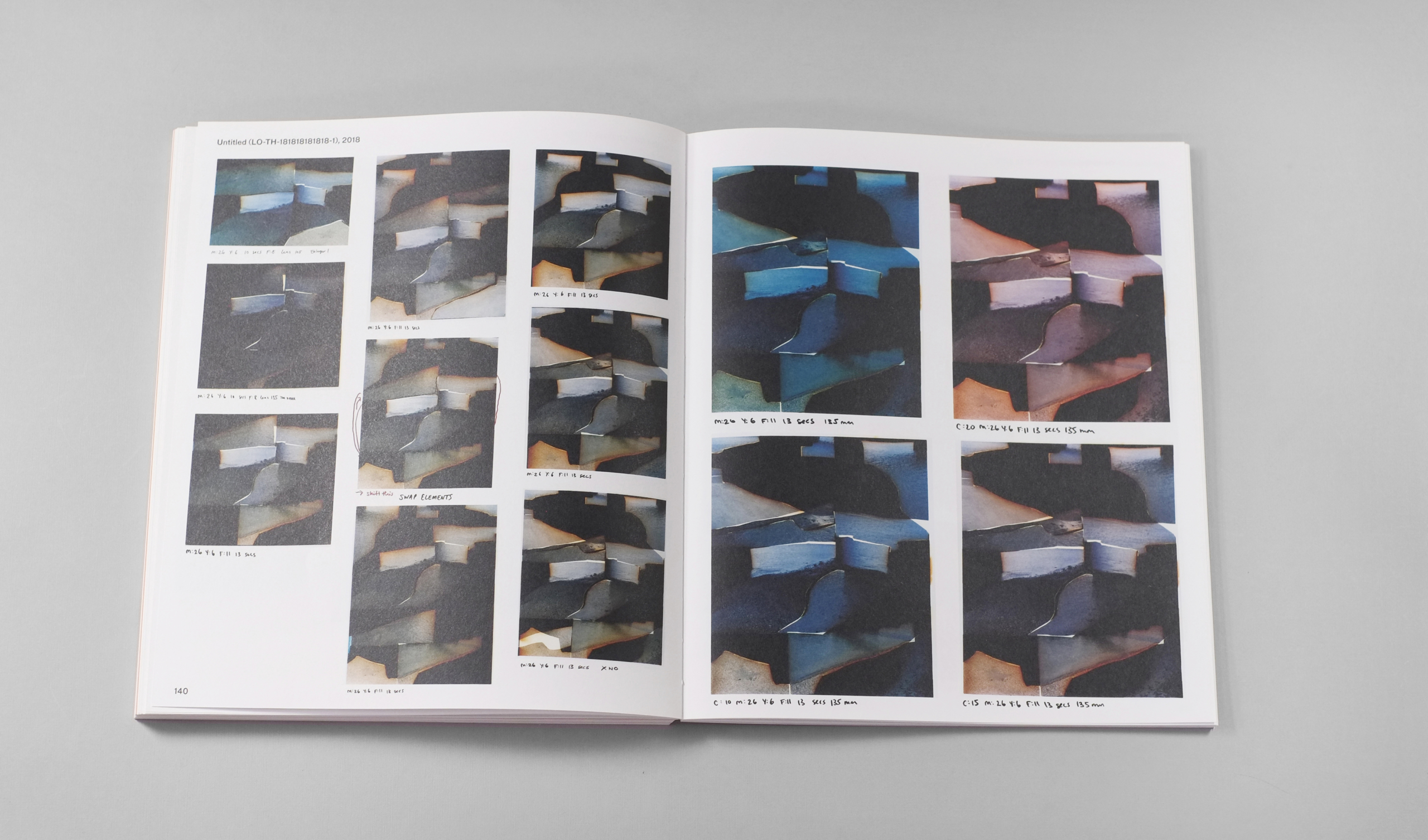

Conceptually, Talmor’s work is closer to collage or low-relief sculpture than it is to painting. The size of the final prints reveals clearly the physical nature of her process, and the different ways that she intervenes with her source material – orange-tinted refractions along the cut edges of the negatives, the blue outlines of scraps of tape, black voids indicating gaps between the negatives; white spaces where they overlap. This foregrounding of process has become an increasingly important part of the work. A recent exhibition featured banner-sized prints of Talmor’s cutting mats, criss-crossed with the multiple traces of her scalpel. The same images appear as endsheets at the front and back of the book. And an entire section of Constructed Landscapes is given over to Talmor’s process; contact sheets and test prints with annotations, (‘too blue!’; ‘one-off print due to fix running out.’…) along with the complex system of notation that she uses to keep track of the relationship between the tiny fragments of each negative and the individual images to which they belong. Most startling are the shots of the composite negatives themselves – fragile things that behave unpredictably, often moving around in the enlarger. Their delicate, lacy appearance shouldn’t surprise; the empty spaces between individual sections are clearly indicated by the areas of deep black on her prints – but it does. That images which appear so solid and monumental should be based upon such insubstantial foundations is an impromptu metaphor for the increasingly fragile relationship between our day-to-day experience of our environment, and the ecosystem that sustains it.

Some may feel that Constructed Landscapes gives too much away – that this generous revelation of Talmor’s secrets robs the work of its mystery. But it’s precisely this close attention to process that makes her work so compelling and so conceptually rich. Because landscape is, after all, less about what is out there, and more about what we make of it.

All images courtesy the artist. You can buy Constructed Landscapes here.