Interview – Daniel Szalai

Novogen debuted at the BredaPhoto Festival 2018. To challenge the conventions of advertising and product photography, Daniel Szalai covered an entire wall with dauntingly slick, minimalistic portraits depicting 168 almost identical-looking chickens, cast against a bright, azure background.

The monumentally-proportioned installation drew attention to the de-humanised, compassionless process whereby the Novogen White chicken are raised. These animals are kept exclusively for their eggs, a vital ingredient for the vaccine manufacturing industry. According to Szalai, their existence is proof of how alienated human beings have become from nature.

Having graduated from an MA at the Moholy-Nagy University of Art and Design in 2019, the Hungarian photographer is eager to create more work unpicking anthrophomorphic tropes. His newest series, Stadtluft Macht Frei, takes a leaflet calling on Viennese passersby to stray away from feeding pigeons as the starting point – only to highlight the similarity of the spatio-visual logic imposed on these birds to those of social minorities.

How do you see the role of photography in interrogating the relationship between mankind and nature?

From early on, photography has been a tool of conceptualizing, mediating, and to some extent, colonialising nature. It influences how we apprehend nature, reinforcing the boundaries setting apart human beings from their environment. With the right tools, we can reflect on and work against this phenomenon.

I was long interested in the Anthropocene, particularly in discussions revolving around the impact the evolution of technology has had on the environment. In 2018, as a student at the Moholy-Nagy University of Art and Design, I was invited to the Talent Program of the 2018 BredaPhoto Festival. We were encouraged to reflect on the theme of To Infinity and Beyond, and on the difficulties posed by technological advancements. Originally, I was interested in cloning, topics like that, before I stumbled upon the chickens.

Chickens represent a fascinating intersection between the realm of the technological and the natural. They’re animals; at the same time, the ones sold today are very much human-made, designed specifically for human use. The more I worked on this project, the broader it became, with many layers and further implications.

Could you tell us about how you came up with this idea?

I was talking to a friend at an art fair when she pulled out this picture of a chicken factory chock-a-block full of chickens. That’s when it occurred to me that I should create an entire wall of portraits, with dozens of photographs focusing on each chicken. At first, I wanted to keep it simple, play around with the question of individuality, and draw on fairly stereotypical ideas, such as ‘you are what you eat.’

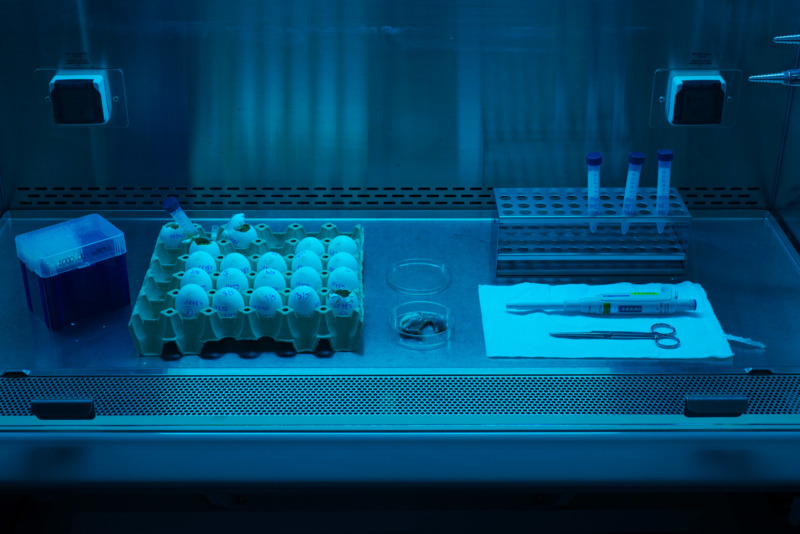

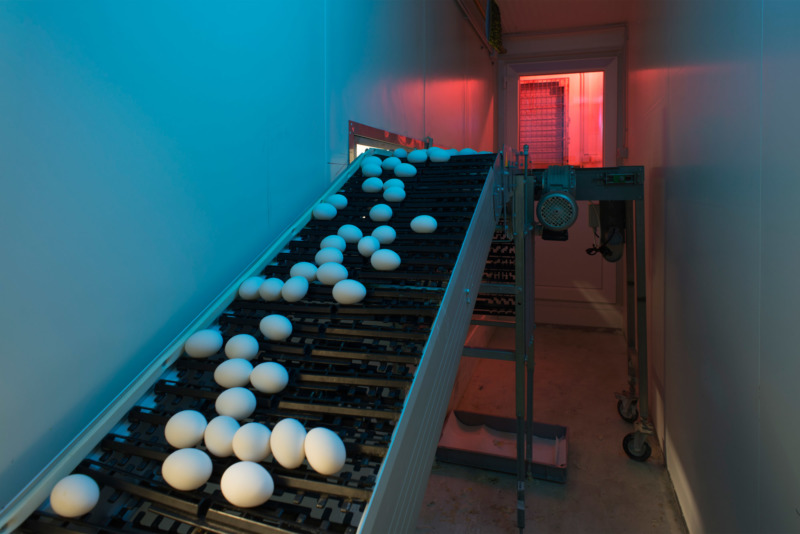

My first visit to the chicken factory made me realise that the topic was much more complex. I became intrigued by the factory itself. It’s a precisely-controlled, artificial environment. It’s not designed for living, but to produce high-quality eggs at. That’s when the project started to explode, as I wanted to add more details.

The chickens raised at this facility are called Novogen White Light. Their eggs are used by pharmaceutical companies to manufacture medicines and vaccines. Their so-called management guide – a user manual for handling the birds – championed a heart-breakingly utilitarian attitude. The sterile, pragmatic language was the exact opposite of the optimism and positive thinking espoused by the marketing materials. I knew I had to include these texts because I feel that they reflect a general attitude towards our environment.

Did you consider the series would take an anthropomorphic angle? You use humour to shed light on alienation, on just how removed the average spectator is from the heavily-coordinated reality of chicken farming – and to reveal how little the chickens’ lives are worth.

Everything about the chickens can be translated into numbers. Their lives are examined based on how much profit they yield; how much financial gain they generate. This lends itself for metaphoric interpretations, for an anthropomorphic depiction of human lives. The two tend to be weighed up similarly, which Mark Fisher described very poignantly in his seminal volume, Capitalist Realism:

Over the past thirty years, capitalist realism has successfully installed a ‘business ontology’ in which it is simply obvious that everything in society, including healthcare and education, should be run as a business.

Mark Fisher, Capitalist Realism, 2009

The life cycle of a chicken is divided into two periods. During the rearing period, they’re fed a strict diet to develop the perfect, most-optimal digestive system. During the production period, which lasts until the end of their life, or 90 weeks, they produce large quantities of perfectly identical, high-quality eggs. You can judge whether their lives were worth it by calculating how many eggs they laid and how much feed they consumed. I wanted to show them as actual workers, producers, but at the same time, as the products of human activity.

Could you tell us about the process of setting up a photo studio inside a chicken factory, and the specific difficulties of working in such a heavily-sanitised, precisely-coordinated setting?

The eggs are used for the production of medicines, and the chickens have to be almost as sterile as a pharmaceutical facility. Gaining entrance to the farm was subject to strict regulations; most requests are denied. It’s easier for them to refuse entrance than to handle the potential of you bringing in disease and accidentally causing the death of hundreds of chickens. The procedure of getting inside wasn’t easy either; I had to get naked, take a shower, get dressed in another room, change shoes, put on a uniform, wash my hands, put on a hairnet, sterilise all of my equipment, and so on.

Once inside, I set up the studio lights and I made a little pedestal for the chickens to stand on. The casting, at least at the beginning, was fairly easy! Some models had proven hard to cooperate with because they’ve hardly ever laid eyes on a human being before. I was clad in this oversized, clumsy uniform. The ceiling was very low, so I had to go down on my knees to take the photos. This being an agricultural facility, I had to show up every morning at half-past five and work for eight hours straight. The worst part had to be the noise pollution; with twelve thousand chicken locked up inside, the constant chattering was truly exhausting.

In a previous interview, you mentioned that the history of chicken farming is nowhere near as linear as it might seem, tracing its evolution all the way back to ancient Egyptian chicken hatcheries. Could you tell us a bit more about the role mankind has played in the ‘genesis’ of ‘chicken’ as they exist today?

I always start my projects with research, which is how I discovered about the scientific aspects of chicken farming. I quickly realised that the history of chicken production serves as an imprint of the history of humanity. According to a 2004 study which I read about in Smithsonian, chickens were the first animals to be domesticated. Hailing from Southeast Asia, they have played a different role in different societies. For some, they were a sacred animal, and cockfights were also popular.

Chickens were a popular commodity in Egypt, where there were hatchery complexes to artificially incubate the eggs. Romans loved chicken too; by 161BC they became so popular that a new law had to be introduced to limit chicken consumption to one meal per day. The regulation also stated how much feed a bird can eat, to curb down overfeeding.

The real break-through came about after the WWII., in parallel with the commercialisation of anti-biotics and vitamins. Chickens can only be bred efficiently when kept inside, where there’s no sun. The introduction of Vitamin D has radically changed the way production facilities were set up.

The 1948 Chicken of Tomorrow contest called on American farmers to send in a chicken egg, each raised under the same condition. The ones with the best feed-to-meat ratio were then used to create the most-optimal chicken species. According to ‘How the Chicken Conquered the World,’ published by the Smithsonian magazine,

Modern chickens are cogs in a system designed to convert grain into protein with staggering efficiency. It takes less than two pounds of feed to produce one pound of chicken (live weight), less than half the feed/weight ratio in 1945. By comparison, around seven pounds of feed are required to produce a pound of beef, while more than three pounds are needed to yield a pound of pork.

How the Chicken Conquered the World

Some say that if our civilisation died, an enormous amount of chicken bones would be excavated. Chicken bones and plastic, and of course, concrete. We’re a society of plastic and chicken bones. Chicken is a product and a symbol of global capitalism, and somehow it also enables it.

Were there any challenges with putting together the exhibition display?

Originally, I wanted to have a huge wall of chicken portraits. The installation allowed me to emphasise the sheer scale of mass production, and to evoke the conflicted notion of individuality. I wanted it to be a densely-packed, narrow space, to make the viewer feel as though they’d been forcefully locked inside this environment with the chickens. Eventually, the project grew bigger. I ended up also including a series of documentary images of the vaccine production, marketing texts, and a soundscape capturing the constant chatter of the animals.

Do you intend to pursue a similar approach in the future?

I enjoy pursuing an objective, descriptive, systematic approach, which also leaves space for alternative readings. I’ll continue exploring the topic of animals because it enables me to chalk up questions about certain societal conditions from a more autonomous point of view. These structures, these processes are deeply embedded in our society. When referring to animals, I get the chance to provide a more thorough, more versatile, objective, unusual interpretation.

Daniel Szalai’s next exhibition will open at the Robert Capa Contemporary Photography Centre, Budapest, in the autumn of 2019. The event marks the closing of PARALLEL – The European Photo Based Platform.