Interview – Morgan Ashcom

Stanley Wolukau-Wanambwa: Your book Leviathan ends with a quotation from an unattributed allegorical text dated back to the second, third or fourth century AD called The Physiologus, and the last lines read: “He, guest of the ocean, in his watery haunts Drowns ships and men, and fast imprisons them Within the halls of death.” The title of your book, Leviathan, a name which refers first to an ancient biblical sea monster, but also to Thomas Hobbes’ classic 17th century work on the proper ‘natural’ structures of government. So I want to start by asking you what are you allegorising in this work, and can you explain how the place in which you’ve made these photographs is emblematic of the epic scale of those associations that frame it?

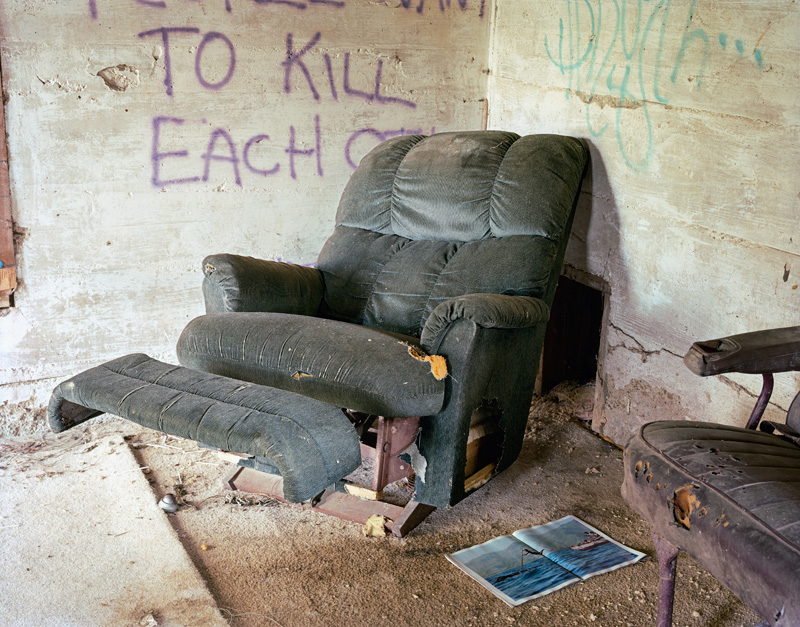

Morgan Ashcom: As you wrote, the symbol of the Leviathan has many possible origins and my book draws on some common threads between them, such as the attempted reconciliation of opposites. For example, the relationship between the sea and the land, the hunted and the hunter, freedom and conformity, nature and artifice, what can be seen and not seen. Many of the works associated with the symbol of the leviathan are often sprawling and verbose. Hobbes’ Leviathan is a brilliant work of rhetoric as is Melville’s Moby Dick. On the other hand, The Physiologus quote, with its brevity and directness, felt to me like a two minute punk song from the 1980s. It is about a group of sailors who believe they’re on shore leave, celebrating on solid ground, when they’re in fact on the back of a great sea monster. While the photographs contain these opposing elements, it is my hope that they don’t direct the meaning in the typical way an allegory functions, but provide the materials for the viewer to construct what they will. A key part of that freedom gets to the other half of your question regarding place and context. The photographs in Leviathan do not address the specific reality of the place where most of the pictures were made. What’s left are those common threads, some of which I mentioned earlier, things that we all share in, a tragic and comedic existence rooted in incomplete meanings. In my experience, photographs are fluid and fragile things. It’s a bit of a cliché now to say this, but photographs tell me very little specific information on their own. I’ve included minimal text in Leviathan partly because I want to preserve the fictional possibilities of the photographs. The title and the text I’ve included function like a crack in the door to my process, a process that started long before I made the earliest photograph in the book. More text might also give the impression that I know more than I do about the work, when in reality I’m still learning. The subconscious is mostly leading the way and it is up to me to dutifully hurry behind photographing and scribbling notes. I’m left to sort these pieces out later. I have access to my observations, imagination and experiences, but there is also the unconscious that shapes things, and it does what it wants and at times offers very limited explanation. Its creative potential resides in the accident of its discovery and a willingness to engage with it. I wanted the limited context I gave in the book to reflect those realities and possibilities.

So where and when were the photographs made, and what do they (at least superficially) describe?

Leviathan was shot between 2009 and 2012. The majority of the photographs were made in the hills of southeast Ohio at a small community called Skatopia. Outside of those pictures, one photograph was made in Virginia and two were made in Maryland.

What was it about the life of this small community that encapsulated or drew together those opposing forces you mentioned earlier, and kept you making photographs there over the following three years?

The place itself doesn’t hold those opposing forces. Life there, or anywhere really, is too messy for that. But I can think of one example that was clear to me. Originally I was drawn to Skatopia because I saw two opposing scenes that I was familiar with. One was the urban skating culture I was part of for over thirteen years, and the second was the rural farmland surroundings of my youth. These two cultures had existed separately for most of my life but there I found them converging in harmony. Initially, that familiarity drew me back to make photographs, and heightened my sensitivity for discoveries that came later. After five or six weeks of shooting over the course of that first year, my interest began to shift from the place to what was going on in the photographs. This shift is what sustained my interest for years. It was in the photographs themselves and not the world in front of the lens that I could immerse myself. The photographer Robert Adams said that the goal of art has never been to be synonymous with life but to show something of reduced complexity providing coherence, form and beauty. This is central to the way I think about my work.

The photographs are littered with overlapping patterns of cyclicity on the one hand, and destruction or violence on the other. They come in the form of the curve of a highway skirting a listing hill, in the shape of improvised wooden structures, basins of water fashioned from animal bones, or in the form of explosions, cranial wounds and the drip of fresh blood. There are allusions to myth and legend, to epic and mundane cycles of life, and to a tension between anarchy and renewal. What are you reconciling photographically in these images, and do they relate in your mind to the realities of Skatopia, or to other larger issues?

I mentioned a few earlier, the relationship between the subject matter that points to the sea and the rural landscape depicted in the photographs. Some photographs appear to depict a hunt, but the thing pursued and pursuer is not entirely clear. Others contain chaotic subject matter brought into order by the composition of the photograph. In regard to the realities of Skatopia, I think people have a tendency to associate photographs with places and people. Photographs are good at purporting to show how things are, but that quickly evaporates under the spotlight of investigation. What we’re left with is illusion, and I mean that in the best way possible. The writer Flannery O’Connor said the kind of vision the artist “…needs to have, or to develop, in order to increase the meaning of his story is called analogical, and that is the kind of vision that is able to see different levels of reality in one image or one situation.” She continues, “Although this was a method applied to biblical exegesis, it was also an attitude toward all of creation, and a way of reading nature which included the most possibilities, …[an] enlarged view of the human scene.” I like that bit about the enlarged view of the human scene. That’s the stuff we all share in. So it does return us to the world, but not in a direct way. How could it? The photographs are distortions. I think we’ve come to a point with photography where it is possible to practice and interpret it in purely fictional terms; in a way that makes no claim to how things are, no claim to naturalism, and yet is still rooted in the visual language of realism.

So do you mean by this that you and your photographs make no claim on who is present, or what occurred in the place where you made them? Do you mean that the only relationship to specific people they depict, in the specific place and at a specific time they are depicted is a formal relationship? A relationship that flows from “the visual language of realism” as it is constructed by you and your use of the camera?

It can’t just be formal. I’m trying to get at something between subject matter, photographer, medium, viewer and form. It’s a possibility that is separate from these diverse elements, each operating as vague interlocutors between one another. This space is difficult to put into words but I think the author Donna Tartt came close when she wrote, “…between ‘reality’ on the one hand, and the point where the mind strikes reality, there’s a middle zone, a rainbow edge where beauty comes into being, where two very different surfaces mingle and blur to provide what life does not…” With Leviathan, the photographs led the way, and the book itself expands on the mingling of different surfaces.

I notice that you’ve used an opening gambit with a small number of sequenced images before the title page, and that you’ve also used gatefolds in the book. How did the photographs lead you to sequencing the work and designing the book?

Over the years I went through six different book dummies for Leviathan. One key moment in the development came from looking at three photographs of a wooden frame laid into the ground. I was looking at them together in sequence and they suggested an elliptical process, like breathing, an action that extends out beyond the scope of the book. They appear in the beginning, middle and end. The first of these frame pictures is in that opening sequence you mentioned and along with the other two pictures next to it, one of a mountain side and one of a fire, which establish rhythms and themes that repeat later like a chorus. Gatefolds are inherently elliptical but at the same time, they upset the rhythm and experience of flipping through books. I became more interested in using the gatefold as a device when these elliptical things emerged in the photographs and I began expanding on them in the sequencing. The gatefold in Leviathan begins and ends with these pictures of water basins. I had two photographs from opposing sides of the basin and I was trying to decide which one I wanted to use. I had them pinned next to each other on the wall of my studio, and saw that together they looked like a set of eyes. So I just decided to use them that way. This is very far away from the backstory and original intent of how these pictures were made, but a lot of the decisions in the book flowed in similar fashion.

So the figures in the pictures can become framing devices in the trajectory of the story of the images?

Yes.

How do you see the portraits functioning in relation to these narrative and elliptical images?

They’re all a part of the same constellation, one that is in constant motion. The portraits could function as narrative foils or harmonizers. They could show signs of ambivalence, comedy, hostility or somewhere in between. There is no one way a portrait functions. Pictures change over time so I’m skeptical of certainty. The portraits that were included depended largely on intuition, again the subconscious at work.

I’ve been reading a few different essays about realism of late, and in one from 2003 Terry Eagleton makes the important claim that “[a]rtistic realism, then, cannot mean ‘represents the world as it is’, but rather ‘represents it in accordance with conventional reallife modes of representing it’,” which I take to mean that modes of realism are historically specific and not absolute, and that the characteristics by which we establish a work’s realism shift over time. Eagleton continues: “But there are a variety of such modes in any culture, and ‘in accordance with’ conceals a multitude of problems,” which is an argument for an array of ways of dealing with differing realities, and which is also an acknowledgement that there are no guarantees that all modes will be equally legible. The subject of realism came up in a conversation I had with David Campany on his book Gasoline, and he argued that “[i]n modernity realism is a moving target. Maybe photography, or those with vested interests in it, thought they could freeze realism the way the shutter freezes action. The hegemony of the mass media magazines did that for a while. But their stranglehold on the conventions for realism is over. This makes form much more of a live issue than it once was. Realism does not have a form that can be taken for granted. We must fight for it in the midst of things.” All of this is by way of a preamble to the following: if a photograph in fact doesn’t tell you a great deal, why does that mean for you that one must abandon any claims whatsoever for its relationship to real things out in the world? Why is it that if a photograph is not conclusively factual, that it must be treated as entirely fictional? Isn’t that an overreaction that runs the risk of opening the door to rank forms of pluralism, where everything is equally valid and nothing means much of anything at all?

I am making photographs that have a relationship to the world. However, my photographs make no claim to a direct relationship. In his essay “Aesthetics or Truth”, Tod Papageorge writes, “When we think about photographs rather than novels, however, we seem to feel that we are dealing with a distinctly different process. The usual suspension of disbelief that we make for books, poems, paintings, and even films does not appear to be appropriate in the face of the photograph’s faithful depiction… That we may be confusing the truth with a particular form of visual description rarely enters our minds…as long as photographs are confused with or, more precisely, identified with their subjects, then we are going to run in circles when we discuss them….” So the photograph of the group of people sitting around a campfire in Leviathan, makes no claim to those people aside from how they looked from a particular view the instant the shutter was tripped. William Faulkner said, “It takes sixty years to create a complete and rounded human being, but the writer hasn’t got that much time. He’s only got thirty minutes, or at the best, three or four hours, and so probably any writer has made a composite picture. It’s people he knew or things he imagined, things he read, things he heard, but he wouldn’t bother with trying to reduce to paper or to put onto paper any living creature.” On its own, a photograph is entirely too limited to make much of a claim on people, and I would never attempt to do so. It is out of respect for the people in front of the lens at the time the shutter is tripped, that I make no claim to them with my photographs. What brought me to make the photographs in Leviathan is informed by those subjective ingredients that Faulkner mentioned. But the viewer can’t possibly know all of that from the picture because of its limitations. But therein lies photography’s strength in creating illusion and meaning from fiction. What the photograph lacks, the viewer fills in with imagination fuelled by their own memories. So now we have two subjective experiences and a photograph colliding, forming something like what Thomas Hobbes called a compound memory (combination of unlike things), a waking dream, or a fiction of the mind. I don’t see the connection between photographs in a fictional context, rank pluralism, relativism, or lack of meaning. Quite the opposite. Fiction, or art, can locate meaning in life despite a multitude of possible interpretations or creative approaches.

I think you’re absolutely right to say that fiction has precisely those capabilities, but surely photographs do not, because they have an inherently fragmentary and static relationship to duration, because they have no voice to give us access to interior experience, because they can’t establish any chronology in which effect follows cause. I think what I’m struggling with is the fact that I understand your sense of the limitations of a photograph, specifically its partiality and its brevity, to imply that you can only speak to their figurative or rhetorical form, and not to their content. In a sense, you own the perspective but disown the interpretation by refusing to give it? Papageorge’s American Sports, 1970, or How We Spent the Vietnam War, for instance, is an excoriating account of American culture during an extraordinarily long and brutal war. He makes astute and persuasive use of photography’s rhetorical capacity to fuse together what a photograph denotes (baseball players running out onto a field) what a photograph can connote (soldiers dropping from Hueys and running into battle). Those photographs aren’t ‘identified’ with their subjects, because the title of the work clarifies his allegorical intentions, and changes the quality of our attention toward a reality that is both present in the moment, and utterly outside of the frame. His photographic attention to strife, entertainment, collective behaviour, social divisions and institutional power enables that work to deal with historical reality, without pretending to biographical knowledge or making definitive claims. I see something similar in Leviathan, which to my mind doesn’t pretend to ‘knowledge’ of the intrinsic nature of the people it represents, but which does position their activity, their freedom, their iconoclasm and their revels within a post 9/11 moment that stands for the sea monster in The Physiologus: i.e. the ground on which they stand.

That’s an important insight referring to the indirect return to the world I’ve been attempting to describe. For me, the content of a photograph is a depictive achievement that stands apart from the reality from which it was made. It has a capacity for a multitude of readings depending on context, similar to words and language. Photography and literature both ask us to fill in different forms of imaginative information based on their respective limitations. Fiction making is like a large room with many windows and doors from which we can enter. I’m in favor of opening up that room to any creative medium, though we may have to agree to disagree on this point in photography’s case. I’m glad you brought up Papageorge’s photobooks. In another of his photobooks, Passing Through Eden: Photographs of Central Park, he writes, “The pictures, even with Adam and Eve in them, were never more than literature anyway; with the approach of the Flood, the book simply picks up the threads that tie the Bible to Chaucer, Shakespeare, and page six of the New York Post….” The Eden book is one I return to regularly and perhaps is relevant to some things I’m doing in Leviathan in terms of symbolism, metaphor and openness to suggestion. The symbol of the whale and photographs that suggest whale hunting scenes recur throughout Leviathan. It is a metaphor neither favoring or disfavoring a political, sociological, or historical reading over a biblical, pagan, literary or subjective personal one. However, the context of Leviathan is weighted towards the illusion of people freely pursuing their passions in a somewhat isolated state of nature. Between the covers of the book is a porous world on the verge of change. You’re right to point out the moment in history we’re currently in, and I think it is true that every photobook is influenced in some way by the time in which they’re made (if not consciously by the artist, then possibly through the perception of the viewer). We’re approaching 15 years since the attacks on 9/11. We’re also 22 years on from the Waco siege, which was the first big news story I remember following when I was young. Both still seem fresh and somewhat compounded. I know that’s a strange thing to put into words and I don’t mean it literally, but I believe violence is a part of us all despite where or when we live. In the opening chapter of Moby Dick, Ishmael reflects on events of his time that contain a fresh relevance to our own, “And, doubtless, my going on this whaling voyage, formed part of the grand programme of Providence that was drawn up a long time ago. It came in as a sort of brief interlude and solo between more extensive performances. I take it that this part of the bill must have run something like this: ’Grand Contested Election For The Presidency Of The United States.’ ‘Whaling Voyage By One Ishmael.’ ‘Bloody Battle In Afghanistan.’”