Interview – Syd Shelton

For the final part of our ‘Revolt and Resistance’ issue, we speak to photographer, activist and graphic designer Syd Shelton. From within a collective of artists, musicians and political activists, Syd photographed one of the UK’s single most important political youth movements of the 21st century, Rock Against Racism.

Between 1976 and 1981, Rock Against Racism utilised music to counteract an anti fascist/ anti racist climate that was prevalent within the UK. Undeniably British and grass roots in spirit, the movement staged a series of events, rallies and concerts uniting a disenfranchised youth, at odds with the system and each other.

In the current wave of political uncertainty, his work offers a new generation insight into how a group of young people were able to use their frustration and creativity to highlight issues that contributed to change in attitudes in British culture.

Under the banner of Rock Against Racism you have worked extensively on a number of different events as an activist and also a photographer. How did you get involved?

In 1976 racism in Britain was becoming ‘normalised’ with the Black and white minstrel show on prime time Saturday night TV. Black, Asian and Irish people regularly used as the butt of dumb jokes from a stream of comedians and the National Front gained an electoral foothold. Eric Clapton’s racist tirade at his Birmingham concert was too much for photographer Red Saunders (one of the founders of RAR) he with others wrote to the music press calling for “a rank and file movement called Rock Against Racism to fight the racist poison”. He ended the letter “Who shot the Sheriff, Eric? Cos it sure as hell wasn’t you” The response was phenomenal and over 800 people replied in the first week. I met Red in these early days and got involved firstly as an activist and secondly as a photographer.

How would you describe your work?

I have always described my photographs as a graphic argument and reject the view that the photographer is somehow an objective observer. I am a very subjective visual artist with a clear political point of view which I express through photography which is my language.

What was your involvement during the protests?

As an activist I was very much involved as a part of the RAR collective, organising gigs and marches as well as photographing them.

Were you ever commissioned to shoot the pictures that you took?

I wasn’t commissioned this was an insiders view, if you like I was embedded in the movement. Many of the pictures I took were for the RAR fanzine Temporary Hoarding which I designed with others in the collective over 14 issues in the years 1976-81.

RAR seem to gain momentum very quickly I’m presuming partly through word of mouth in the 70s and 80s but there was also a wealth of zines, flyers and other printed matter. Can you talk us through the way of engaging with people.

We sometimes used Temporary Hoarding to advertise future events but more important was the music, left wing, and alternative press such as Socialist Worker, New Musical Express and Melody Maker and posters. London street posters were controlled by a crew in North London headed by a guy called Terry The Pill and we would deliver van loads to him to paste up. If you didn’t do it through him, they wouldn’t last long.

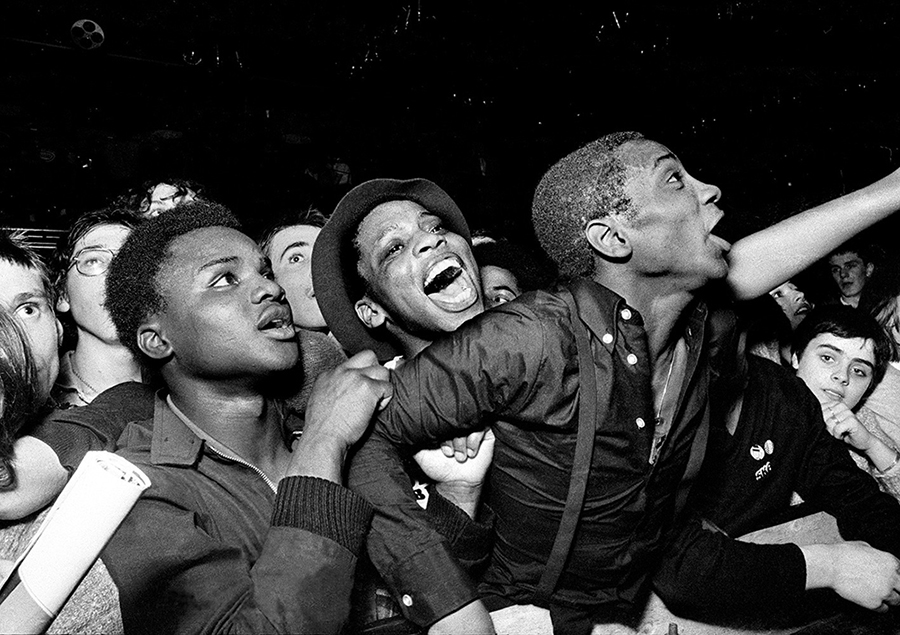

We also had a national network of RAR groups who did all the footwork outside of London. But the other reason that it grew so fast and so big was because of the marriage of Reggae and Punk, which were both rebel music and bringing together bands such as the Ruts and the Clash with Misty in Roots or Steel Pulse was in itself a political act. We saw Temporary Hoarding as the means to take the argument further and to also raise issues around Ireland, South Africa, homophobia and sexism. It was in a format which folded down sometimes to A4 and sometimes A3 but opened up to an A1 or A0 poster which people could put up on there walls.

Did printed matter make people feel like they were more involved in the movement?

Of course and the RAR stall at the back of the gigs was always buzzing. We sold several million badges which was our main funding. We also sold a stickers, poster, T-shirts and records.

At what point did you realise that the marches had gained the momentum they had?

We called our marches ‘carnivals’ which we had borrowed from the Notting Hill Carnival where so many RAR bands had done their musical and street fighting apprenticeships. The first big Carnival we did jointly with the Anti Nazi League. We chose Victoria Park in the heart of Tower Hamlets on the day before the May Greater London Council elections because the national Front had gained 17% in the previous ballot. We begged as much stage and PA gear as we could from contacts we had made in the music industry but we didn’t just want a big gig we wanted an event so we also booked Trafalgar Square. Everybody told us that no one will march 7 miles from central London to the East End but we persisted. We had a fleet of flat bed trucks with generators and PA systems which bands like The Ruts and Misty in Roots played on all the way through the streets of London; we had 200,000 plastic whistles donated from Virgin Records.

I got given the job of being in charge of RAR in the square, probably because I lived in Charing Cross Road at the time. I worried as I went to bed the night before that no one would turn up but all night I could hear from my flat people pouring down Charing Cross Road singing Clash and TRB songs. I couldn’t wait and went down to the square at about 7am and already about 10,000 punks and dreads were rocking. We had predicted in our most optimistic mode about 20,000 but by the time the rocking, dancing, shouting procession left it was 100,000 strong and by far the largest anti racist demonstration since the second world war.

How conscious were you of your role as documenter of social change?

For me I had no handle on the historical significance of what we were involved in because we were too close and there was no time to stand back. I never really thought of the pictures as a coherent narrative and it was only when Carol Tulloch persuaded me to take a fresh look at the work thirty odd years later, it became obvious that there was a significant collection of work.

Can you talk us through one of your favourite images?

In June 1977 the Metropolitan Police staged dawn raids on 30 homes in the Lewisham and New Cross area of South London. 21 young people were arrested and accused of being involved in muggins. There was no evidence against any of the young people and it led to a defence organisation being set up. According to investigative journalist Paul Foot the operation was code named ONH which stood for Operation Niger Hunt. The National Front’s response was to organise a provocative march through Lewisham on the 13th of August called the Anti Mugging march. The response from the local multiracial community and anti racists everywhere was outrage and a huge counter demonstration took over the streets of Lewisham. The image of Race Today member and veteran civil rights leader Darcus Howe is at the top of Clifton Rise during the several hours of waiting before a quarter of the entire Metropolitan Police and their entire mounted division attacked to forge a way through for the massively outnumbered NFers. I think that picture works for me because his elevated position on top of the public toilet block enabled me to frame him with the flats behind. Years later he said that David Widgery of Rock Against Racism passed him the megaphone and said “get up there and say something Darcus”. The beaten and dishevelled National Front were quite quickly bussed out of the area but the fight with the police went on all day. 13th of August was the day when my generation took sides and we knew this was serious.

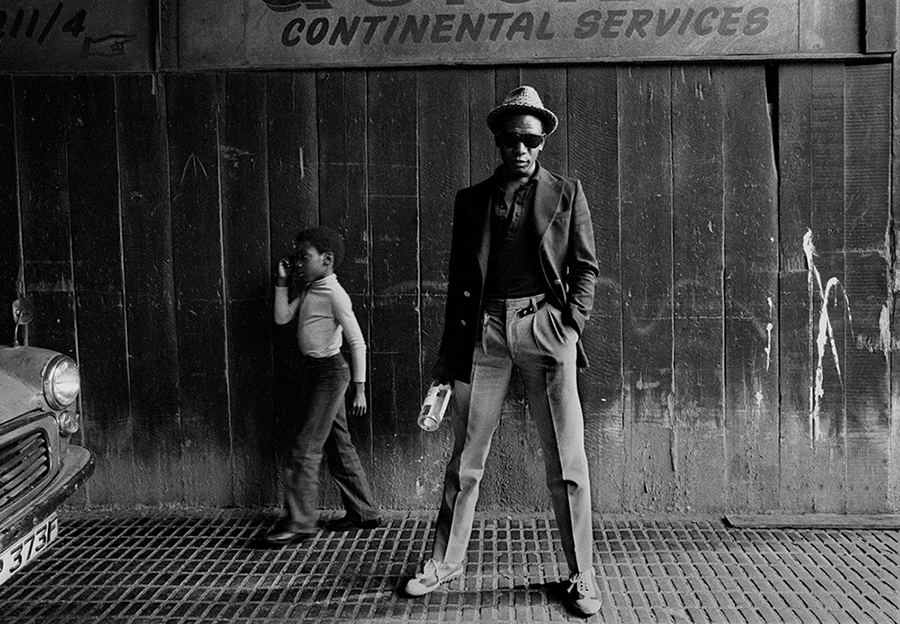

Your work has a definite fashion / style element, is this something that interests you?

I love the way in which the clothes that people wore were not nearly tribal but they were a form of rebellion in themselves, what Carol Tulloch has described as Style Activism. I am more aware about the ‘fashion’ aspect of some of my work than I was at the time and sometimes I was just to close. There is a picture which I really like, they’re wearing Ben Sherman button down shirts, braces and Harrington Jackets. The style has travelled full circle from the Jamaican Rude boys via the reggae loving UK skinheads and back to the rude boys in Yorkshire.

Can you talk to us about the style from this era but more specifically the language of protest dress. What styles defined political affiliations back in the 1970s/ 80s, for example racist and anti-racist skinheads?

Punk and its DIY ethos was all about getting up peoples noses, annoying your parents and rejecting a society which rejected them. The dreads also rebelled against a conservative first generation black British attitudes and wearing hair in dreads was a big statement in itself. Skinheads were wrongly caricatured by the racist extreme who were only a fraction of their numbers and there were an equal number of anti-racist skinheads and black skins. Some like RAR activist Sharon Spike made the journey across the divide after going to RAR gigs.

Why do you think music was used as the impetus for RAR and how did that come about?

We were lucky that chemistry of the ‘punky reggae’ era made it easy to combine the genres and as with clothes there were lots of crossovers of musical style. At the end of RAR gigs we always did a jam session with all the musicians which was fantastic and sometimes the sight of someone like Jimmy Percy from Sham 69 singing the Israelites with Misty in Roots did more for anti racism among the minority of racist who had attached themselves to Sham than a thousand political rants. One of the unifying things about the collective with its wide range of political views was that we all loved the music which was the backbone of RAR.

Can you talk us through the technical aspect of your work?

In the period that I shot the RAR pictures, the digital camera hadn’t been invented, nor the pc or mobile phones or Photoshop so of course they were all shot on film. I used two 35mm Nikon F3s with motor drives and a Norman flash gun. I rarely used colour film because the images were only printed in black and white because the magazines and zines that they were intended for only printed in black and white. The motor drives were important to me because it meant you didn’t miss anything because you didn’t have to take your eye away from the viewfinder in order to wind on the film. I used either Kodak Tri X film or Ilford HP5 which I usually rated at 800 asa or sometimes 1600 and then overdeveloped it in order to increase grain and contrast and drama by reducing shadow detail. I still have the cameras which I used then and what strikes me now is just how heavy two bodies a big flash and a bag full of lenses is. The images which are in the exhibition are all scanned on an Imacon Flextite scanner which is sharp enough to maintain the film grain.

Earlier this year we saw the Black Lives Matter marches both in the US and in the UK. The UK events felt reminiscent of Rock Against Racism, do you feel an event like RAR could have happened in the US back in the late ’70s?

RAR did become something of an international movement and there were RAR gigs in the USA in the 1970s. I was invited by RAR New York to go and talk to them in 79 or 80. They turned out to be largely run by the Yuppies from their then headquarters in Bleaker Street and really it was very different from the movement in Britain.

Why do you think the movement didn’t translate well in the states?

I think that RARs chemistry relied on that explosive fusion of Punk and Reggae and that didn’t exist in the same way in the USA. Punk was much more ‘new wave’ and didn’t have that urban anger and there wasn’t a big USA reggae scene.

What is the role of photographer when documenting a march or protest?

(Of course it is fluid) there is not one approach to making pictures on demonstrations. i recently found some film footage of the battle of Lewisham in 1977 and I noticed myself ducking and diving around with my cameras. What I also noticed, which I had forgotten was that I kept my gear in an aluminium box which doubled as a stand to give me height which enabled me to get shots like the Darcus Howe and often that elevated position would make the shot work.

You’ve previously stated you believed that you could change the world and you don’t feel that young people feel that empowered anymore. Is this something you still feel after the BLM and Brexit demonstrations this summer?

We did feel an enormous feeling of empowerment and for those five years we paid little attention to our careers or money and material things. RAR consumed us but it wasn’t some awful political crusade it was a five year anti racist party and the music never stopped. It was also sometimes dangerous and some of the street confrontations with the National Front were very violent some of us got locked up on more than one occasion. When the police attacked the People Unite headquarters in Southhall in 1979 a dozen people ended up in hospital and Clarence Baker, Misty’s manager was in a coma with a blood clot on his brain, 750 people were arrested that day. I think empowerment comes to each generation in a different form and there is now among young people a lust for a different political involvement like the 400,000 mostly young people who have joined the Labour party since the election of Jeremy Corbyn.

Movements like RAR can’t be bottled and then the lid taken off and they live again in a different time, there is no one formula and that was then and now is different and new forms of protest are emerging like the fantastic national anthem protests. As one of the slogans we adopted from the surrealist said, “All power to the imagination”.

Are there any youth movements / organisations of this generation that you think are inspiring?

Every generation finds ways to get a voice and I think the mass movement around ‘Momentum’ is an inspiration as half a million largely young people have swollen the ranks of the Labour party to make it the largest political party in Europe.

‘Syd Shelton: Rock Against Racism’ exhibition is on tour and opens at Street Level/Photoworks in Glasgow on the 11th of February. ‘Syd Shelton: Rock Against Racism’ photobook is available to purchase via Autograph ABP.