Nigel Shafran’s Dark Room and Stefan Ruiz’s People, selected by Kalpesh Lathigra

© Nigel Shafran 2016 courtesy MACK

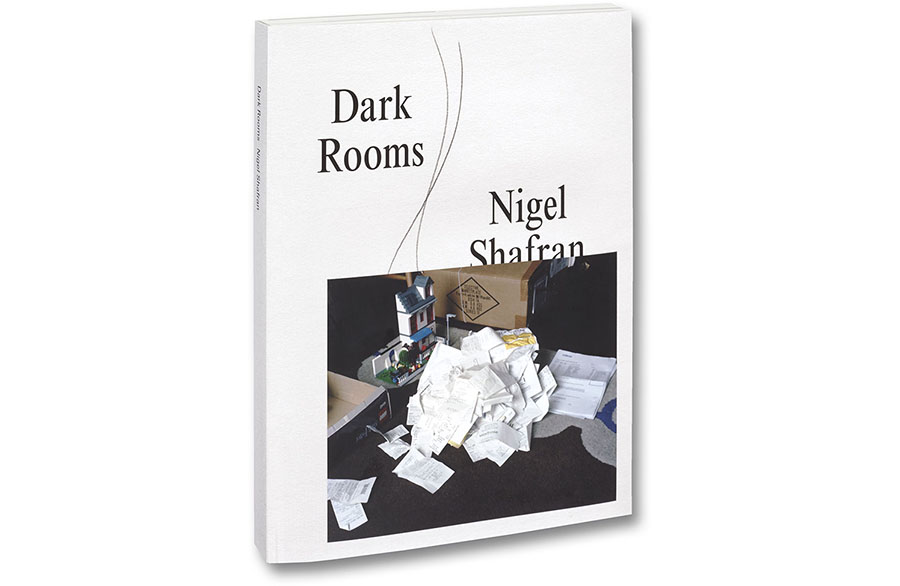

Dark Rooms by Nigel Shafran (MACK, 2016), BUY

I met Nigel Shafran for the first time in 2015 at Photo London, I gushed like a lovesick teenager and subsequently sent an email apologising. But then that’s the effect Shafran’s photographs have had on me over the years.

Dark Rooms is no different, it is five projects interspersing in effect the tenets of life and death, its cyclical nature. This hits home, as a child I was brought up as a practising Hindu to try and let go of the Maya, the materialism that hold us hostage to nirvana thus breaking the circle pronounced in the Vedas, the Hindu Scriptures.

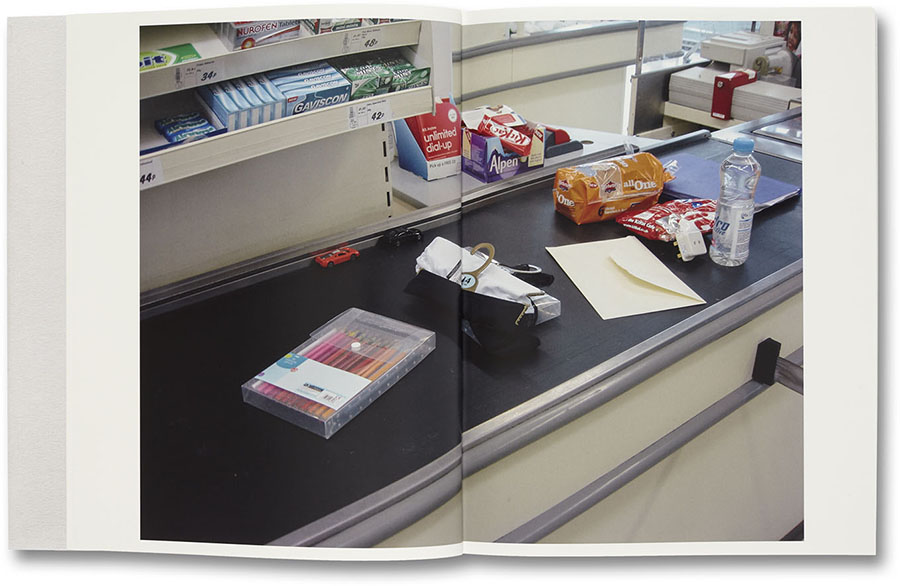

On Saturday mornings, I find myself looking at the beautiful light in my local Tesco supermarket pretty much always at the checkout. A moment of calm transcending in an otherwise stressful activity. It is here Shafran captures the sculptures of packaged food on the conveyor belt. There is a feeling of separation here; who buys what, what is same and what is different and the why. It is human nature played out, a microcosm of the daily choices.

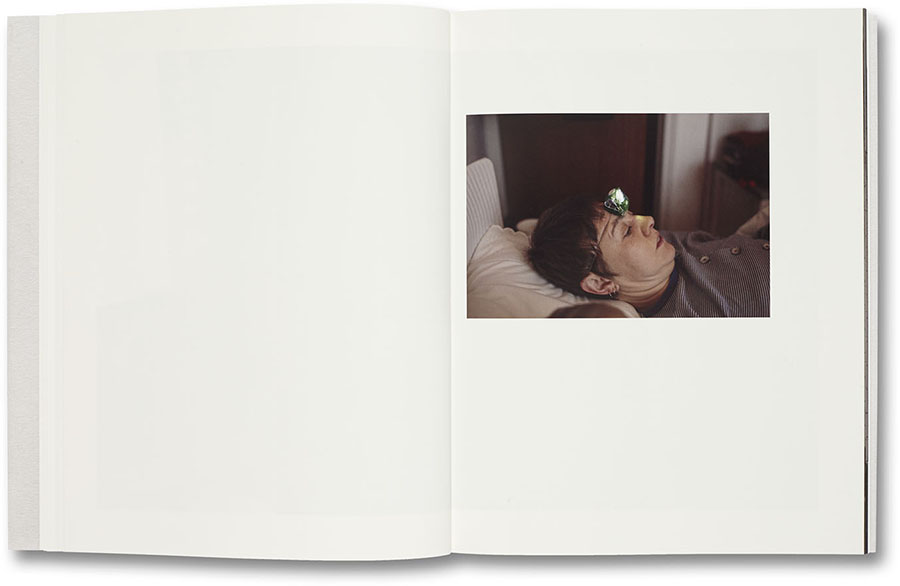

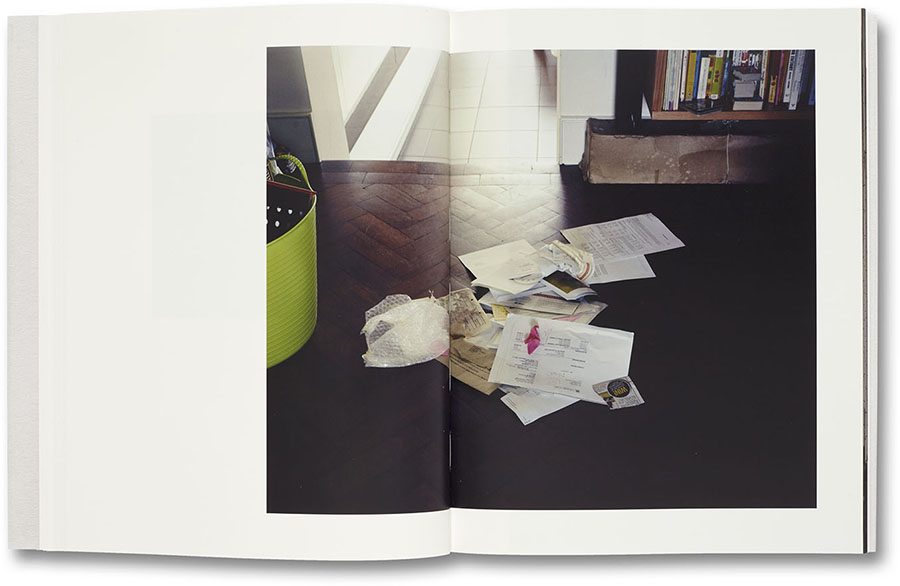

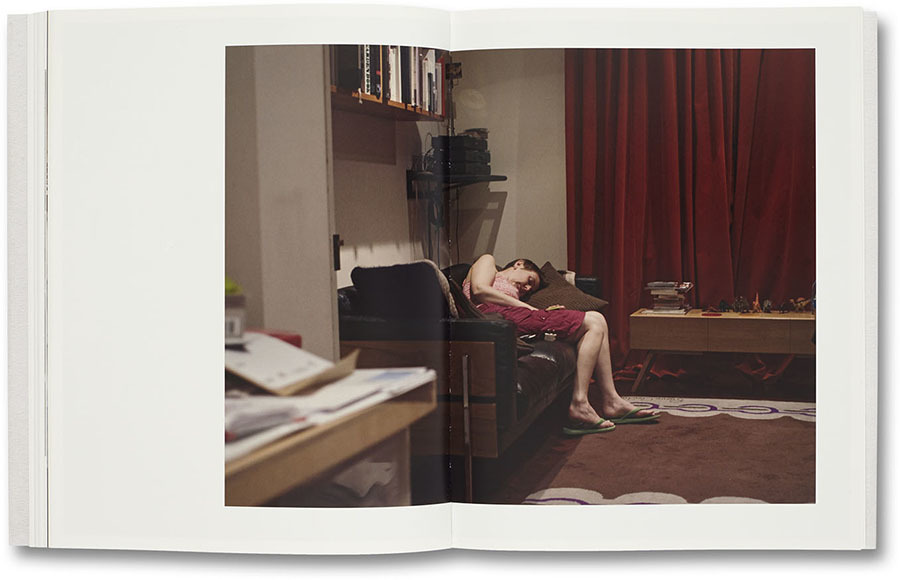

Inside his home we find a string draped and significantly knotted, Lego, trainers, his partner Ruth ironing, piles of receipts and a portrait of Shafran reflected in his computer; the palate is muted. These moments have almost a film set feel, metaphors to the complexities of life as he comes to terms with the death of his parents during the making of the book.

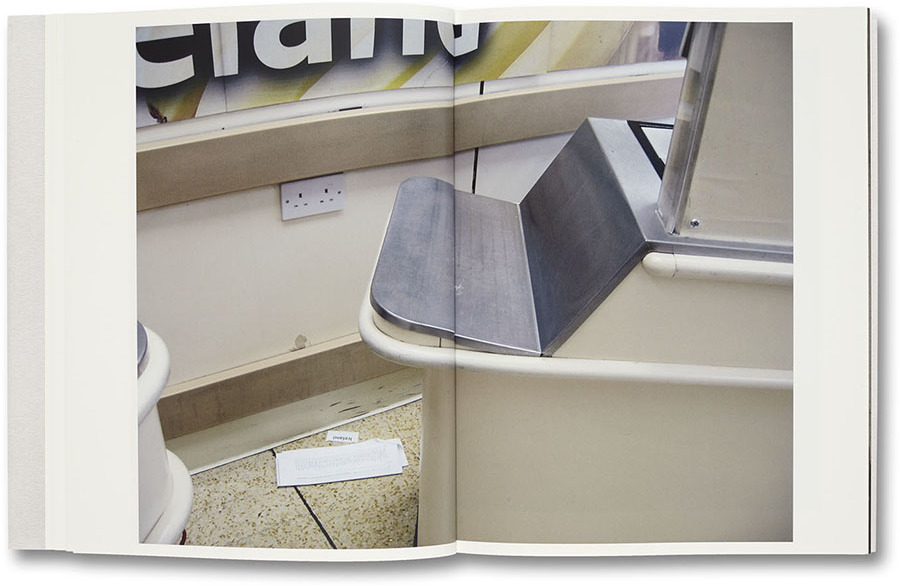

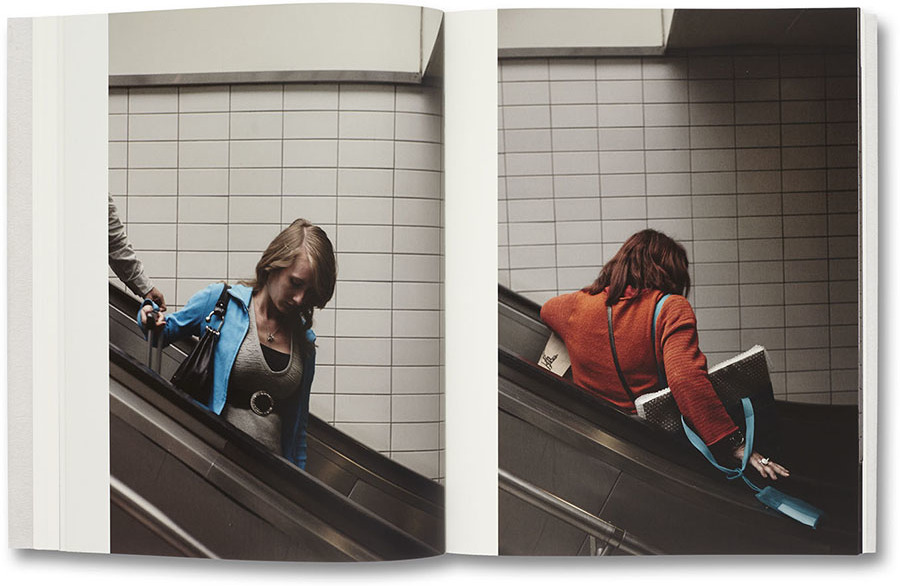

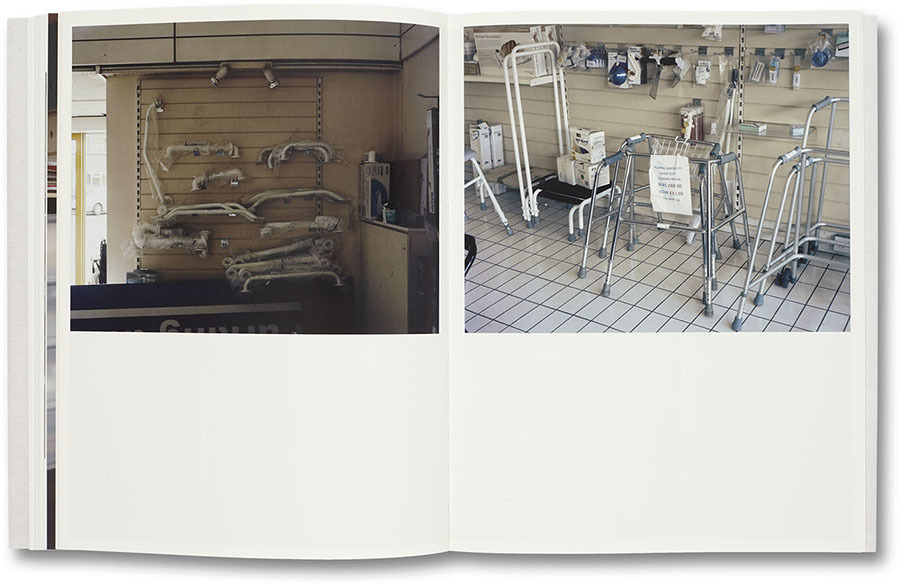

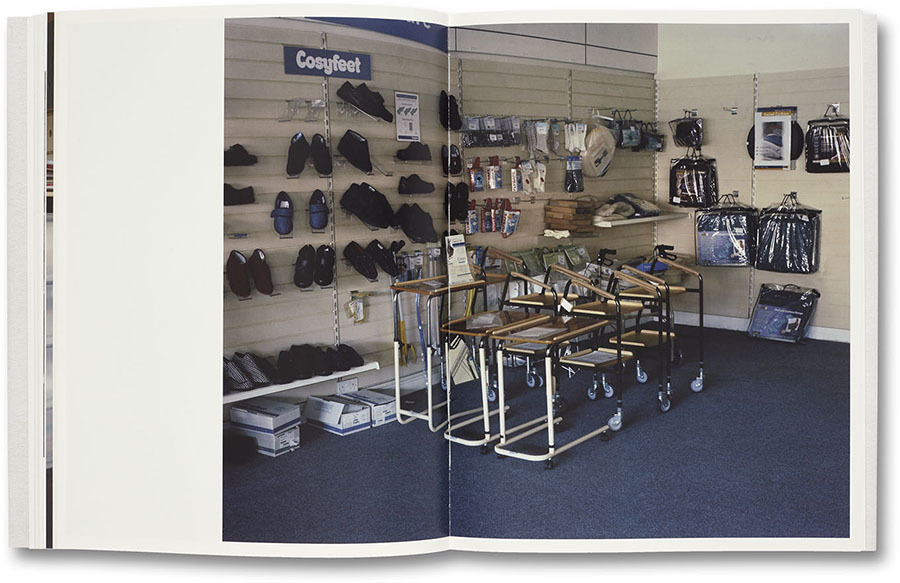

Shafran’s pictures from the past of Charity Shops come back in the form of Mobility Shops and Portraits on escalators on the London Underground have underlying darkness enveloping with the notion of the inevitable, these places and people, us all are hidden in plain sight.

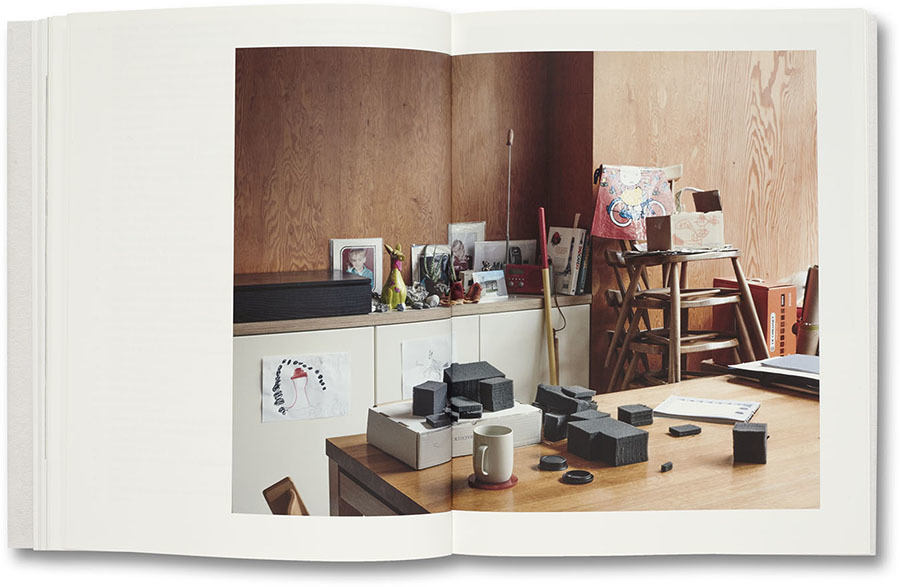

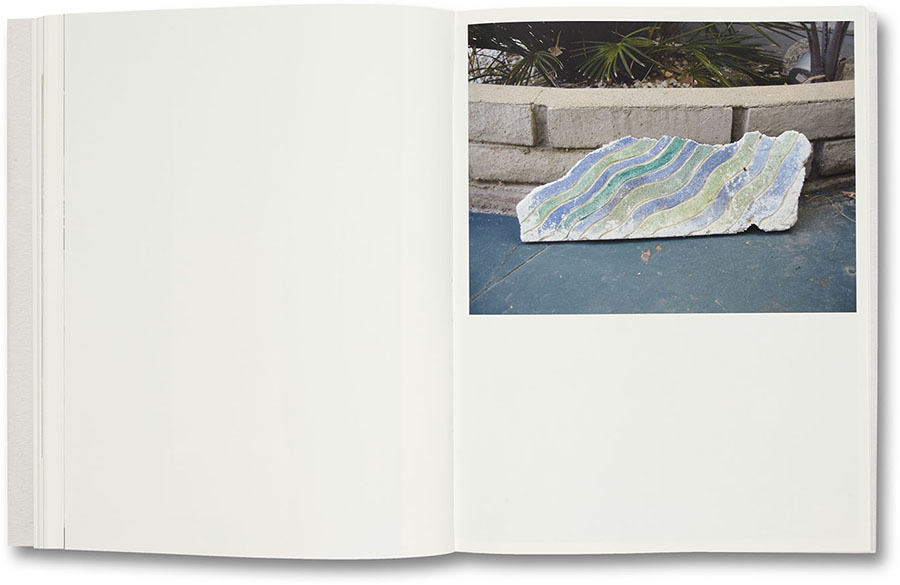

One can feel a lift in emotion when we are taken to Palm Springs and we see the remnants of his mother’s artwork, maybe it’s the light of California but also those who know Shafran’s book Dad’s Office, the difference is palpable.

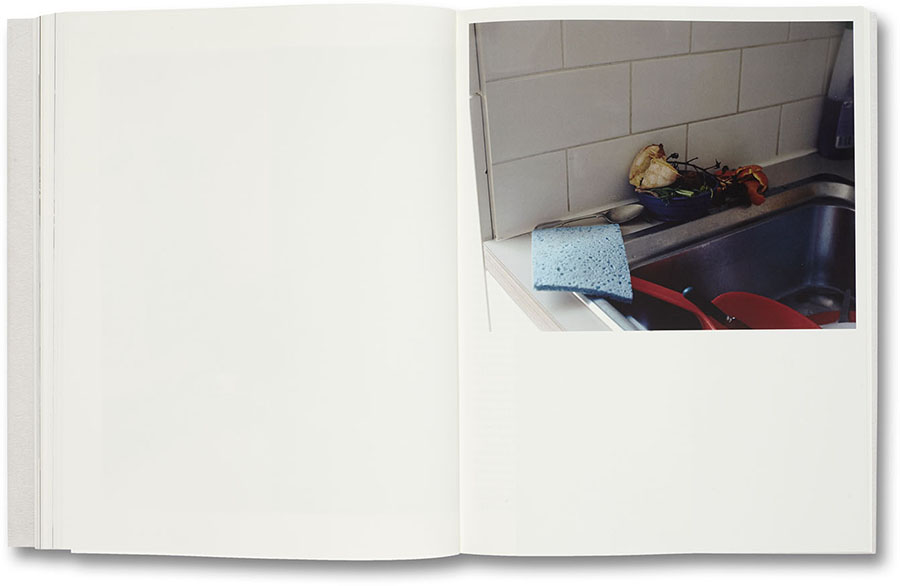

As we reach the end we are treated to little containers balanced on sink tops with things to recycle and compost. There is beauty in Dark Rooms, it reflects the precarious act of happiness and sadness; one cannot be without the other.

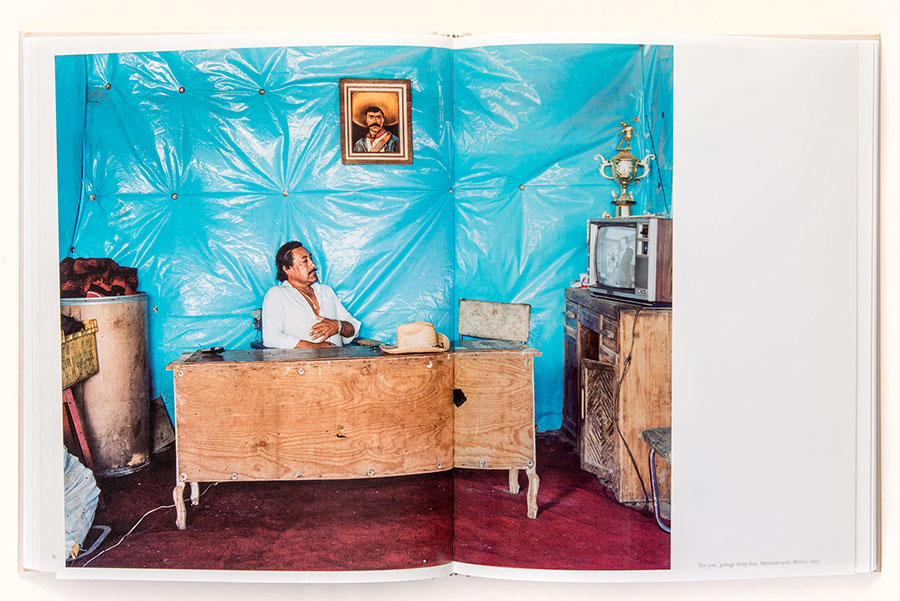

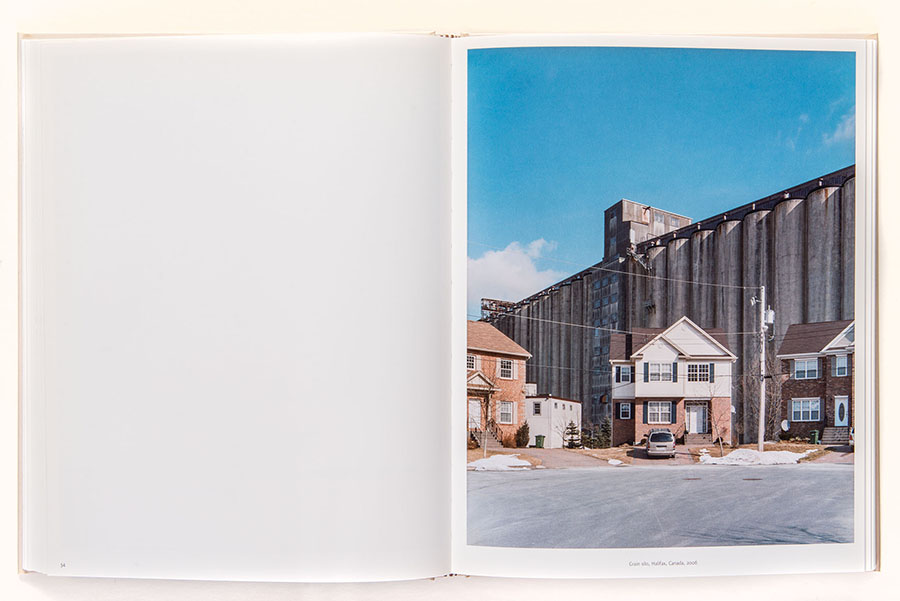

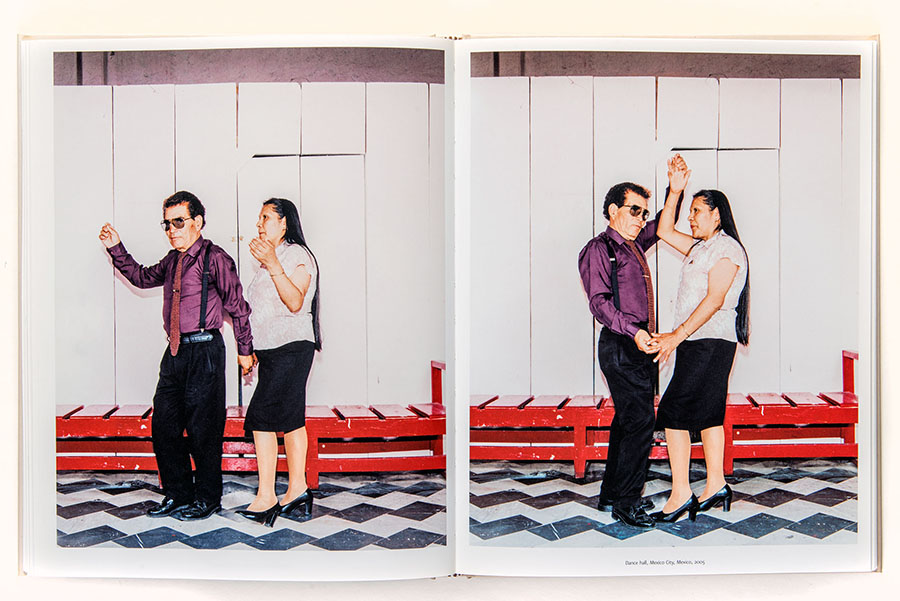

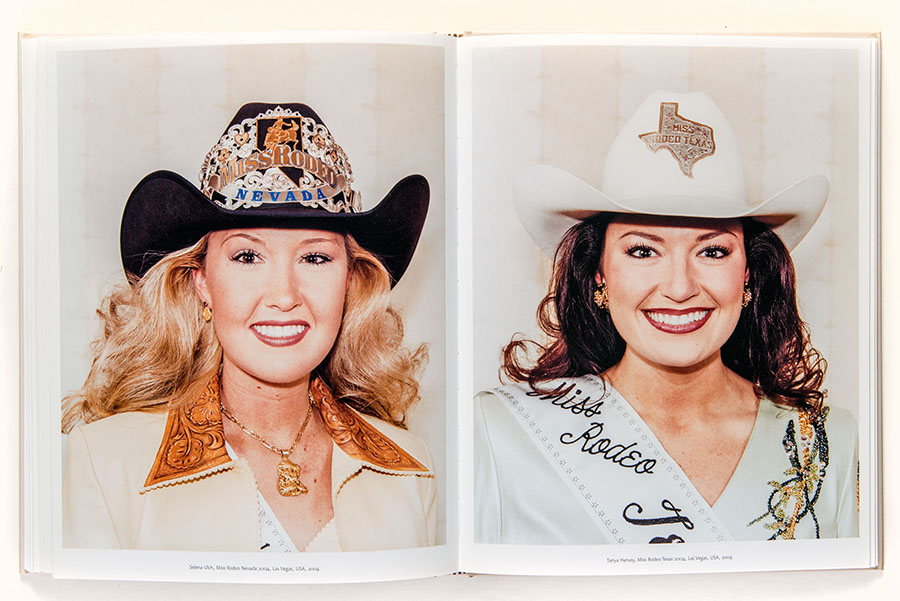

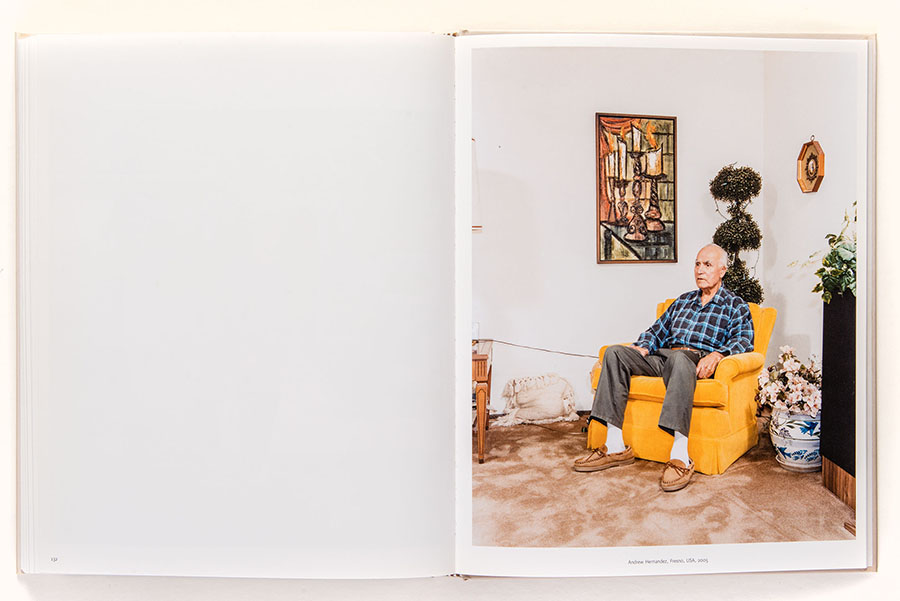

© Stefan Ruiz 2006

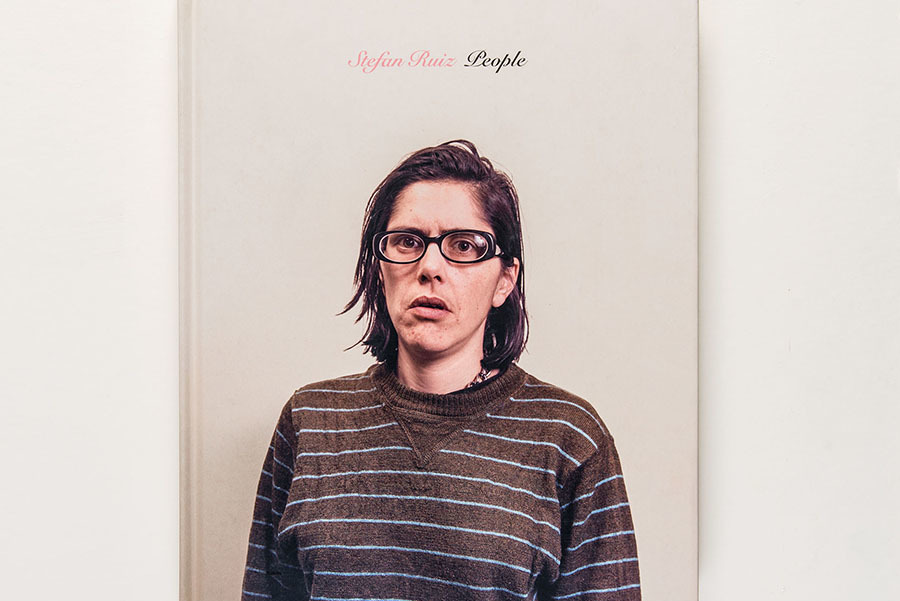

People by Stefan Ruiz (Chris Boot, 2006), BUY

The cover of People, Stefan Ruiz’s first book published over 10 years ago is a portrait of his sister Phe – he writes “This is my sister Phe. She’s a painter. She’s one of my closest siblings. We get along. This was taken in a moment of fragility, but she is quite into the photo.”

Whether it’s Chloe Sevigny, James Brown, a young couple in Birmingham, England, upright landscapes in Chile, or members of his family, there seems no disparity across the World in these photographs until you look closer at the details, the gestures, expressions and body language. It is here that the strength and grace lies in Ruiz’s practice, disarming the viewer and raising questions.

People is made up of both his personal projects and commissioned photographs from editorial and commercial clients. It could be misconstrued as a greatest hits or best of album, which it is not. Its subtle narrative leads us to where Ruiz’s heart and beliefs lie without overt sentimentality.

His early work with prisoners in San Quentin Prison, California, where Ruiz was teaching art, speaks volumes of the trust that the men had in their mentor.

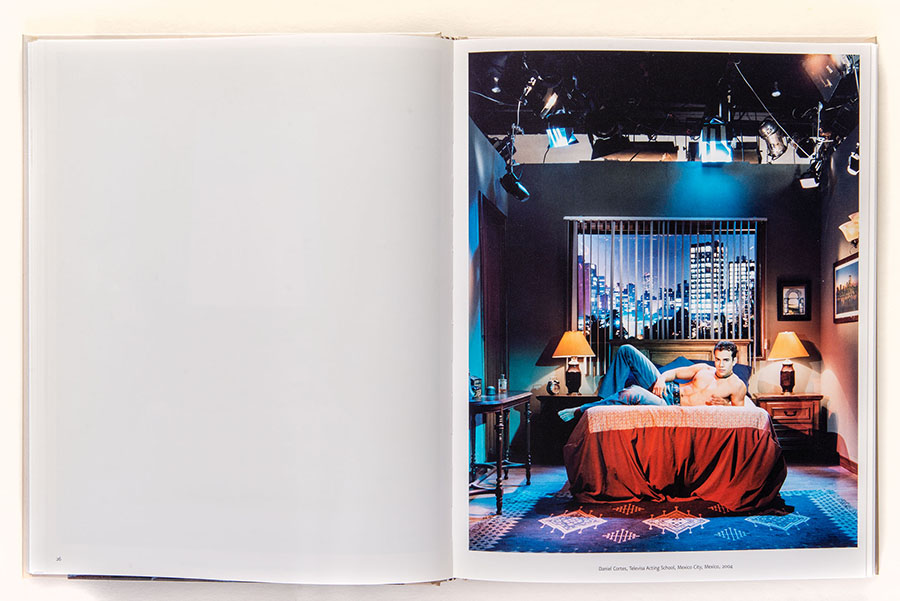

The beginnings of The Factory of Dreams, Ruiz’s celebrated book of 2012 are in People with bare chested actors languishing on beds and maids sitting at tables with the undertones of politics.

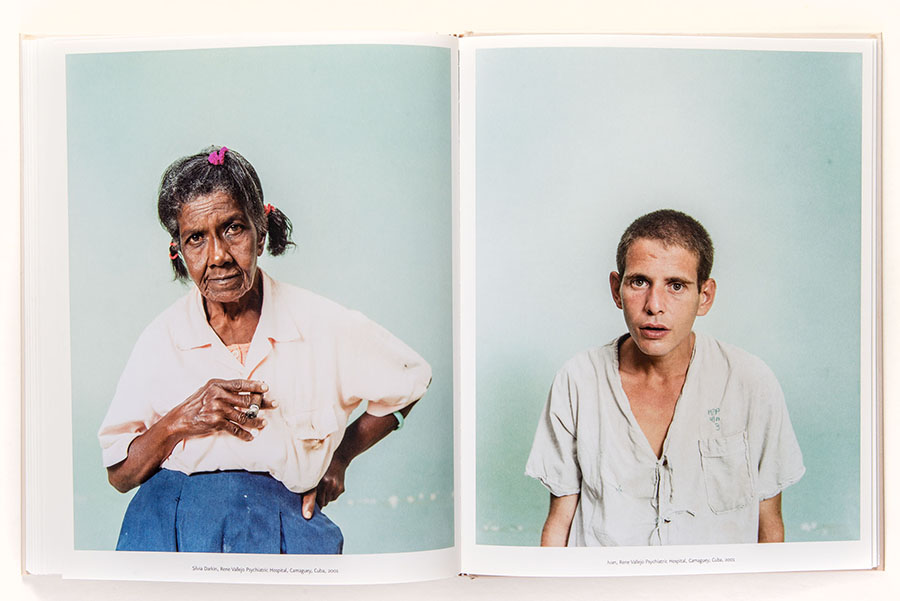

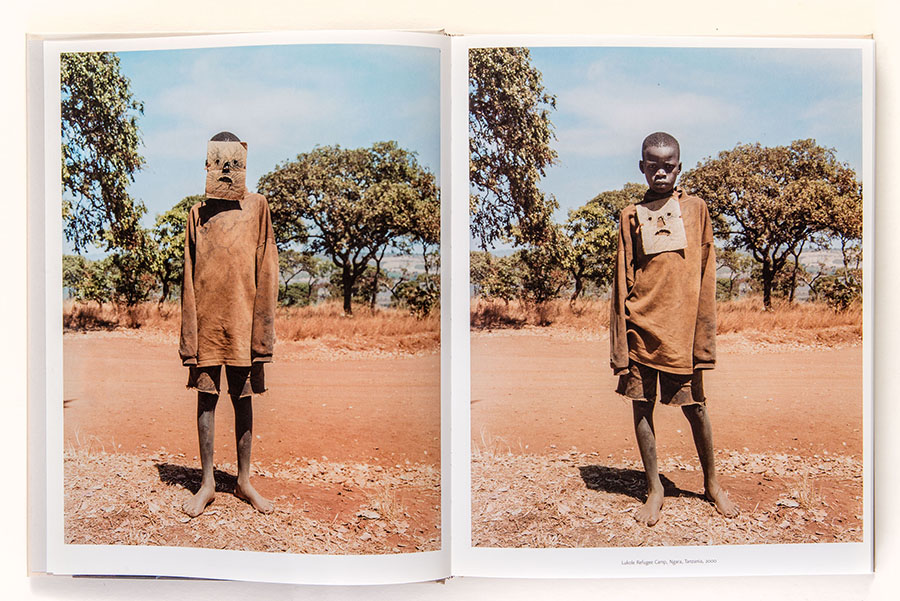

It is of no surprise that Ruiz work is influenced by Flemish and Renaissance Painters. The lighting, composition and palate are laid bare. Every decision Ruiz makes is with authority, whether it’s the Hospital Operating Theatre in Lukole Refugee Camp or Dancers in France. Here I am and Here I am the Subject. It is a conversation and collaboration.

Towards the end of the book we are shown members of Ruiz’s family with the poignancy of the final three plates all taken in funeral parlours. It is apt that the book begins and ends with family.

It is Ruiz’s democratic sensitivity that draws me constantly back.

Kalpesh Lathigra, London, 1971, studied photography at Central St Martins and the London College of Printing. After leaving the course in 1994, he was awarded The Independent Newspaper Photographer Traineeship. Kalpesh worked for The Independent as a staff photographer before freelancing for the national newspapers in the UK for 6 years covering news and features. In 2000 , he gave up working for newspapers and made the decision to work on long term projects and magazine and commercial assignments. In the same year he was awarded a 1st Arts prize in the World Press Photo. In 2003, he embarked on a long term project on the lives of Widows in India, receiving The W.Eugene Smith Fellowship and Churchill Fellowship.

In 2007 he embarked on a new body of work looking at life of the Oglala Sioux on Pine Ridge Reservation , Kalpesh’s first book Lost in the Wilderness was published in 2015 and was recognised by Sean O’Hagan as one of the photography books of 2016. Kalpesh continues to work for leading international magazines alongside personal projects. He has exhibited widely and is a visiting professor at Syracuse University (NY) and Southbank University (UK).