Photolucida Critical Mass 2019 – Our Picks

Photolucida’s annual Critical Mass is an online programme that encourages connections within the photography world. Over a 4 week period, photographer’s of all levels are encouraged to submit their completed projects.

A long-list of 200 shortlisted artists are voted on by a wide-ranging jury to create a Top 50, with this year’s jury including writers, editors and publishers such as Alessia Glaviano, Senior Photo Editor, VOGUE Italy; Joanna Milter, Director of Photography, The New Yorker; Aline Phanariotis, Assistant Artistic Director, Voies Off – Arles, and Patricia Karallis, Founding Editor, Paper Journal. Here, Karallis, selects her picks of the top 50 winning entries.

Sarah Hobbs – Twilight Living

Twilight Living is an exercise in topoanalysis – the psychological study of the sites of our intimate lives. What do we do in our private spaces to assuage our anxiety in the ambiguous times in which we live? There is a weighing down on all of us these days, on our society, and so much of the anxiety of our time is social (and much of that spurred on by politics). Sometimes we dance around topics, trying to feel out another’s philosophies, ‘Am I going to find myself aligned with this person or opposed?’ Turning inward can be a detriment, but we are all so wary of our fellow man, of conversing freely, that it feels like a comfort now to metaphorically hibernate.

The idea of turning away from reality and doing something rash or impetuous, simply as a release or as a way of feeling one has control over something, some act of creation or destruction, acts as a kind of psychological panacea.

In addition to impromptu behaviour, the act of collecting is a careful, methodical practice seen in this work. Collecting is also a type of soothing. But constantly, obsessively looking for (or making) items (of no actual value) to save is not really experiencing life. Collecting feels like an accomplishment, but it isn’t really.

It is more than an impulse… it is a defensive move, initially with the aim of turning disillusionment and helplessness into an animated purposeful venture… it is a device to tolerate frustration…

Werner Muensterberger, Collecting: An Unruly Passion

This idea of salvaging the self and the life one knew is avoidance of society today and all that entails. We are in a truly ambiguous period at present, but in holding on to a past that was comfortable, one cannot move forward in life. One cannot make progress. One is trapped in twilight.

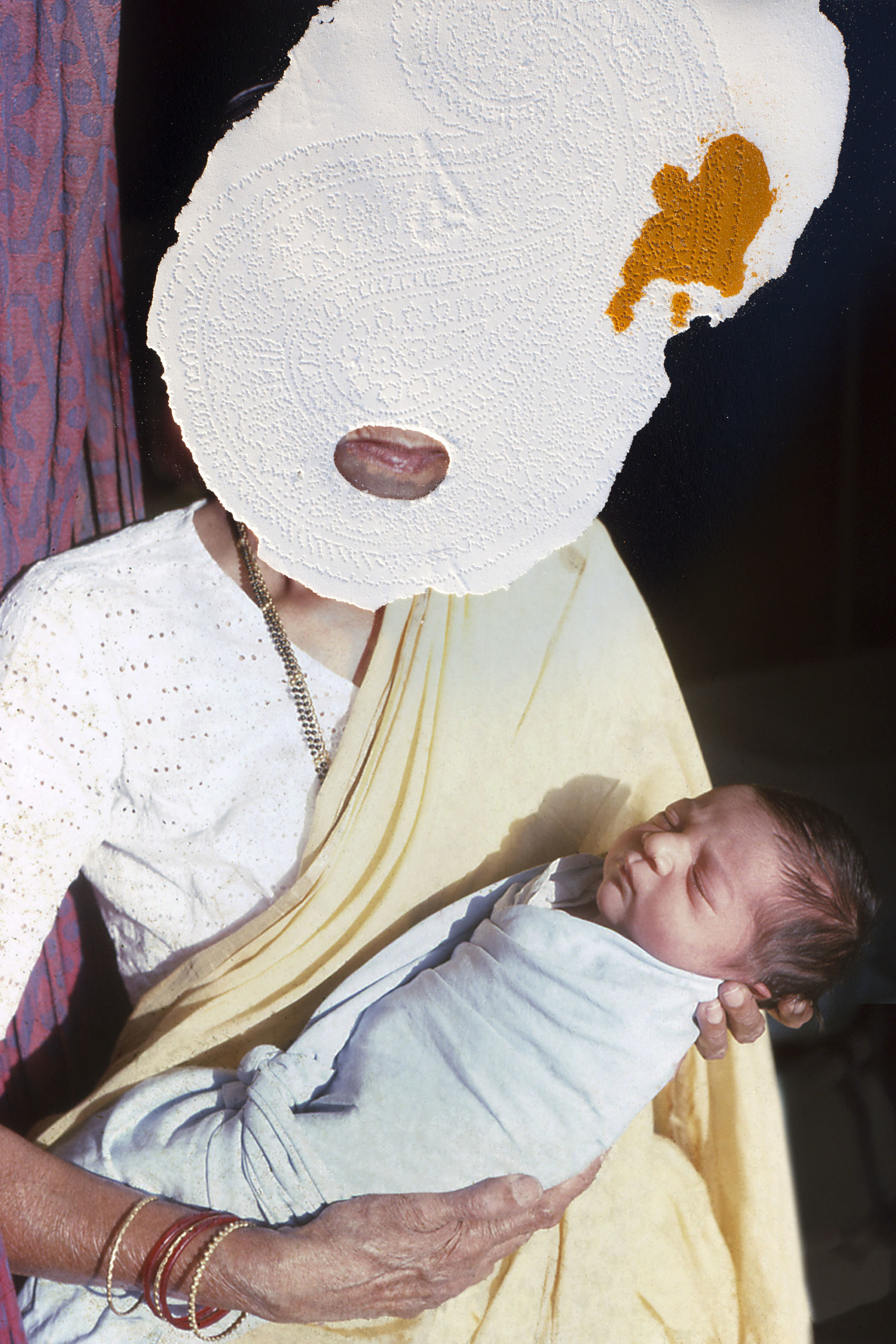

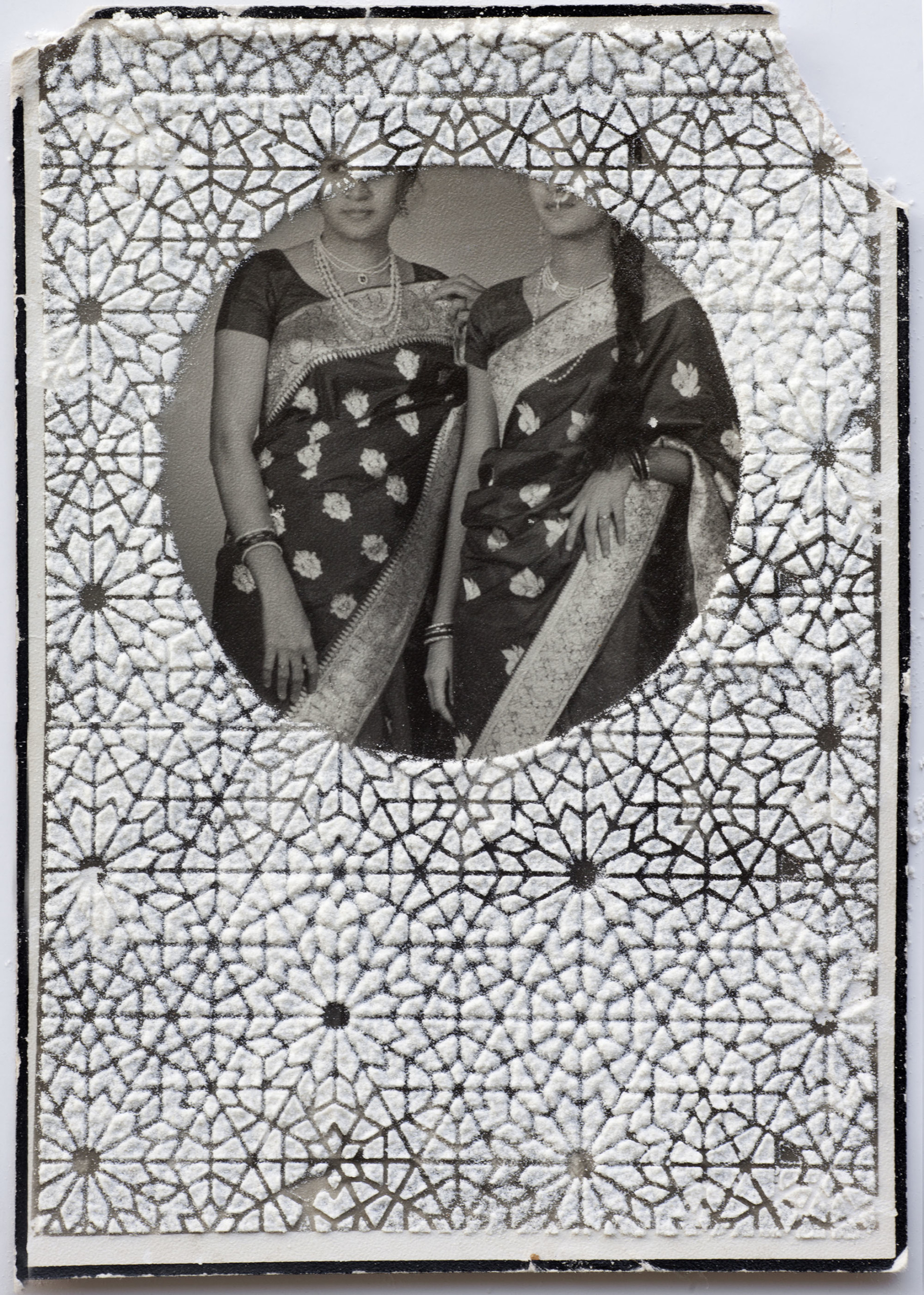

Priya Kambli – Buttons for Eyes

My work has always been informed by the loss of my parents, my experience as a migrant, and an archive of family photographs I brought with me to America. For the past decade, this archive of family photographs has been my primary source material in creating bodies of work which explore the migrant narrative and challenges of cross- cultural understanding, providing a much-needed personal perspective on the fragmentation of family, identity, and culture that are part of the migrant experience.

In the series Buttons for Eyes, my personal narrative is foregrounded – the title referring to my mother’s playful yet nuanced question, “Do you have eyes or buttons for eyes?”. It is a question laced with parental fear. Here, concern was not only about my inability to see some trivial object right in front of me, but our collective inability to see well enough to navigate in the world. And with the benefit of hindsight, those worries have political dimensions that may be read as implicit in the work. In this work, I continue my effort to think about themes of identity, migration, and loss as catalysts for dialogue and the forging of cross-cultural understanding as well as its reflection on the broader cultural context. In Buttons for Eyes, my concern for the past that is lost to me is apparent, but so is my concern for the future and the losses that will come. It reveals that although this work mythologizes the past and present it also plays games with them. It winks, pokes and inverts – suggesting joyousness, mixed with the loss and regret that accompanies us all.

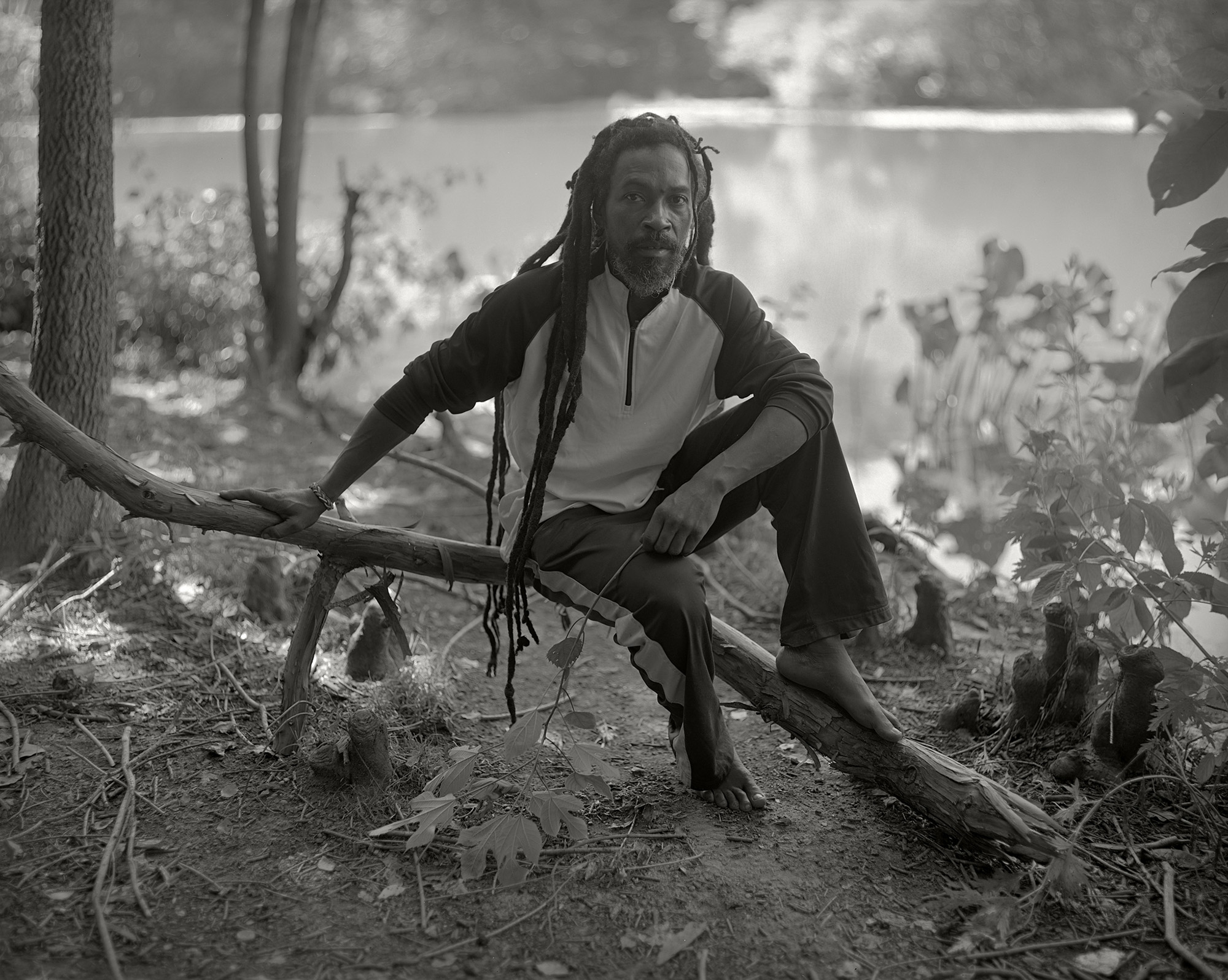

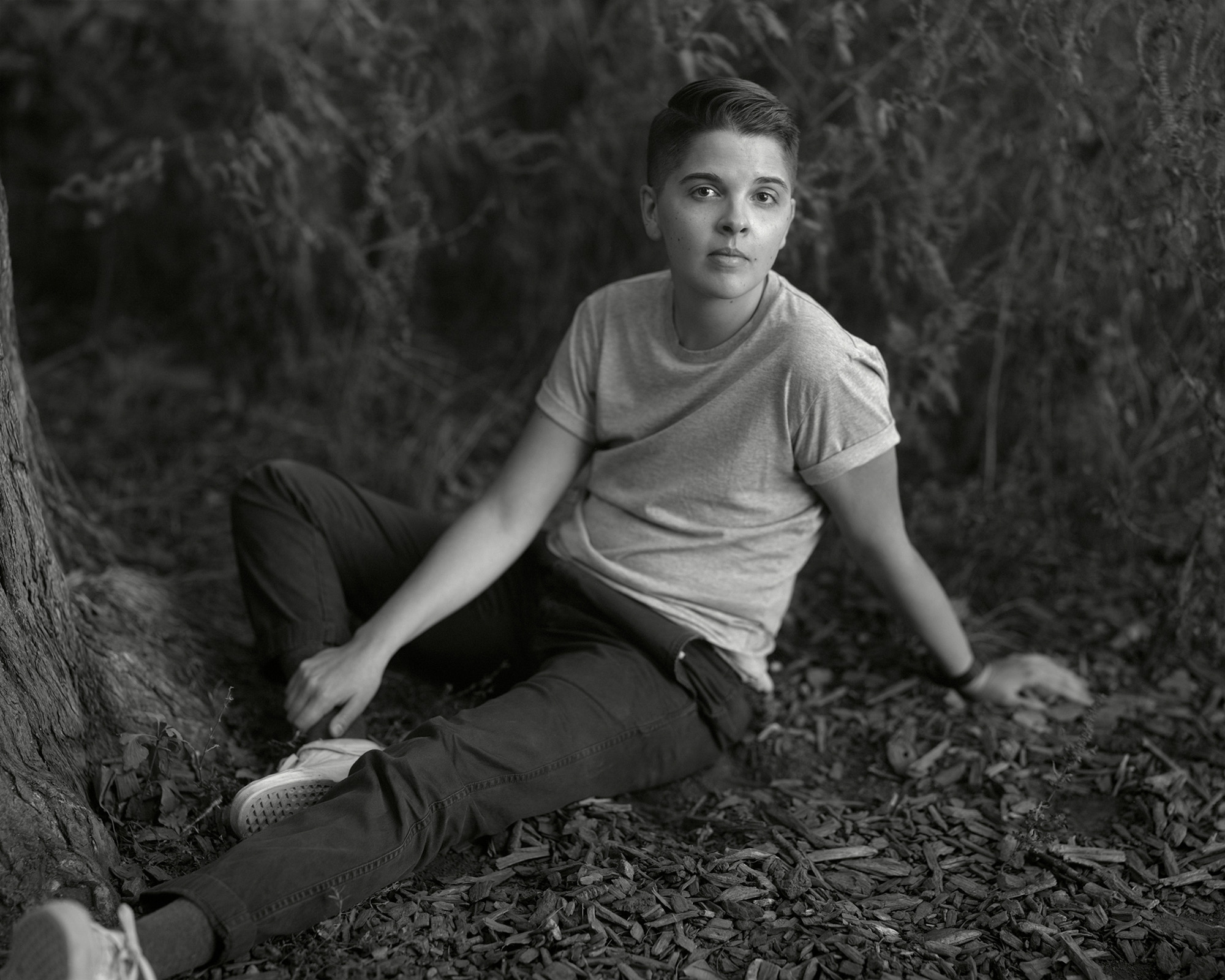

Bruce Polin – Deep Park

Sometime in 2015 I began to regularly pack up my gear and go outside to make portraits of people I didn’t know. It was later on that I realized my Deep Park series was born from a need to create something meaningful, maybe beautiful, in the face of a pervasive and inescapable political ugliness. It’s no coincidence that my need to leave the insularity of my studio and go out to connect with ‘strangers’ began in earnest during the campaign that led up to November, 2016. This series of portraits has been a very organic and physical reaction to the polarization that has enveloped this country since before the presidential election.

The images I was making began to take the form of a project, and it eventually became more cohesive when I decided to focus on people I encountered, specifically, in Prospect Park, Brooklyn, NY, close to where I live. The title Deep Park is a play on the term ‘deep state’.

Prospect Park is the optimal microcosm of New York City’s diversity. My use of its natural assets as a backdrop somehow imparts additional political resonance, given that our public lands and environmental protections are eroding by the minute and climate change denial is now, incredibly, a governing principle. The park is a vast organism, fertile, with secret winding paths and infinite textures and sounds. There are many unique ‘neighbourhoods’ within it. It is very nuanced, just like the people who come to it.

The making of the photograph informs the final image. The process can effectively isolate us, as if an invisible room takes form around me and the people I am photographing. It all happens in a public space. I’m fascinated by how we construct private spaces within larger public spaces. It’s in these private spaces that we can safely forget who we are ‘supposed’ to be. I tend to look for people who might already be in that space, and I approach them with care, trying not to break what they have built. That’s a good starting point.

Raja Kata – Here and There

Sometimes it seems to me that everything is going to collapse. The houses, grey from soot, and the broken pavements will fall on the mine corridors below. I live in a small town in Silesia, Poland, and at some point, there might have been something interesting going on here, but it was so long ago, that it is long since buried in memory. It is neither pretty nor ugly. There is no heritage of previous generations, not even any hint of flair in the current ones. If not for the dead mine shafts protruding from below, my town might be located anywhere. Or perhaps here and there.

In Polish, ‘here and there’ is gdzieniegdzie. But it also has its equivalent in the Silesian dialect, kajnikaj. If we use the latter, my place will become less here and there. This is an obvious form of taming the reality, allowing us to build upon it and create a mythology of sorts.

When I look at the sky over the decaying town, and when I build rickety contraptions I am trying to find means to escape from the place I was born and raised, even though I know that it is a futile attempt.

Caleb Stein – Down by the Hudson

Down by the Hudson (2016-2019) is my ode to Poughkeepsie, a small town in upstate New York. For years I walked obsessively throughout Poughkeepsie, in particular along a three-mile stretch of its Main Street. I grew up in big cities and my conception of small American towns came from things like Norman Rockwell illustrations, so I wanted to see how my photographs matched up with those inherited, almost mythologized ideas of Americanness.

Poughkeepsie used to be home to one of IBM’s main headquarters, but in the early 1990’s they downsized and left thousands of people unemployed. Today there are still several buildings which remain abandoned. In this way, Poughkeepsie is like countless other small American towns that have struggled with deindustrialization and outsourcing. After the 2016 elections, there was a palpable tension as I walked along Main Street. The elections were almost neck and neck in Dutchess County, to the point where you could have practically fit the difference into a crowded bar on a Saturday night. This heated political moment marked a turning point for this project. It wasn’t only about understanding this mythologized conception of America, but it was also about grappling with this conflict through photography.

It was during this time that I started going to the watering hole, an Eden tucked away behind the local drive-in movie theatre on the outskirts of town. The watering hole became a central component of the project because it represented an idyllic space where people from all walks of life came together and let their guard down. The more time I spent at the watering hole, the more I wanted to convey the struggles and beauties of this town with care and tenderness.