Regine Petersen – Find a Fallen Star

Book spreads courtesy of the artist

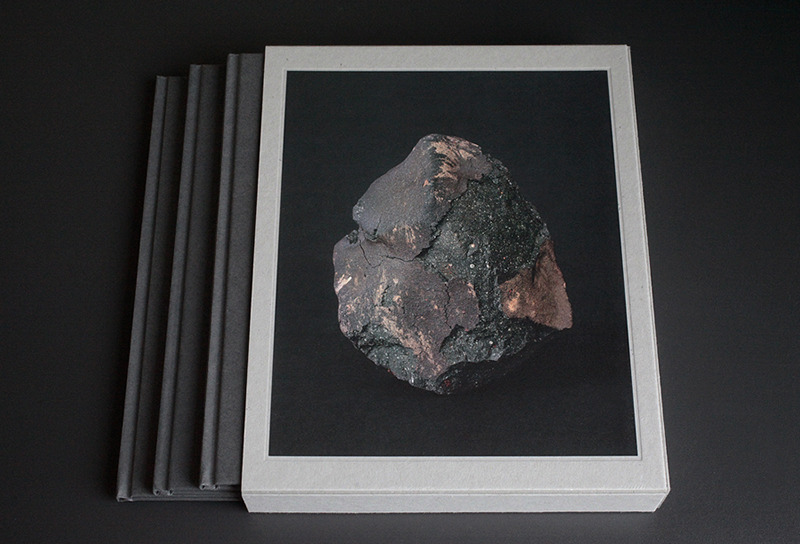

Find A Fallen Star by Regine Petersen (Kehrer, 2015), BUY

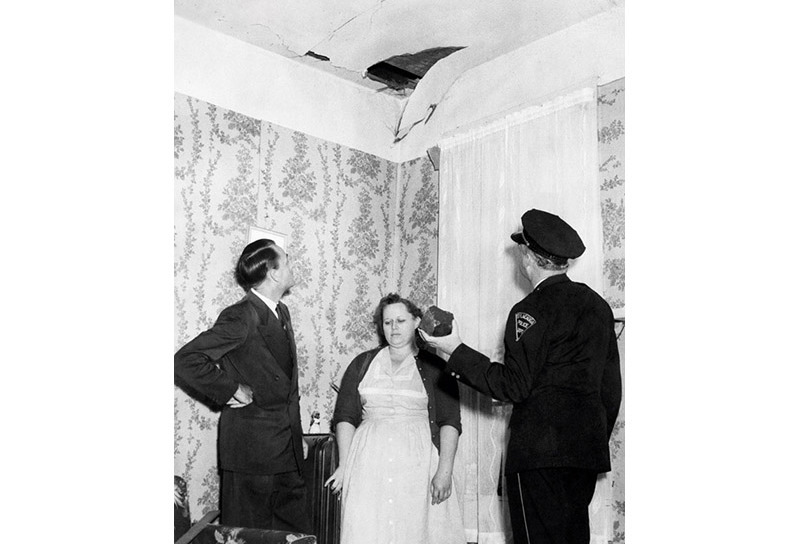

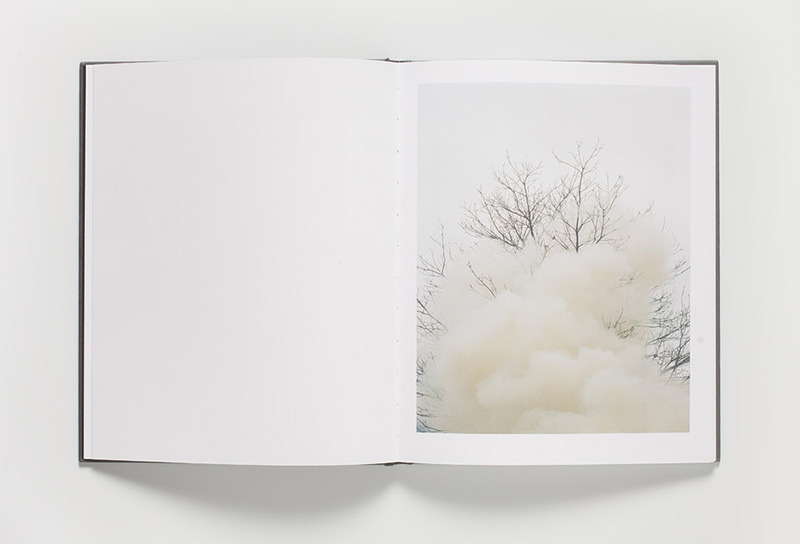

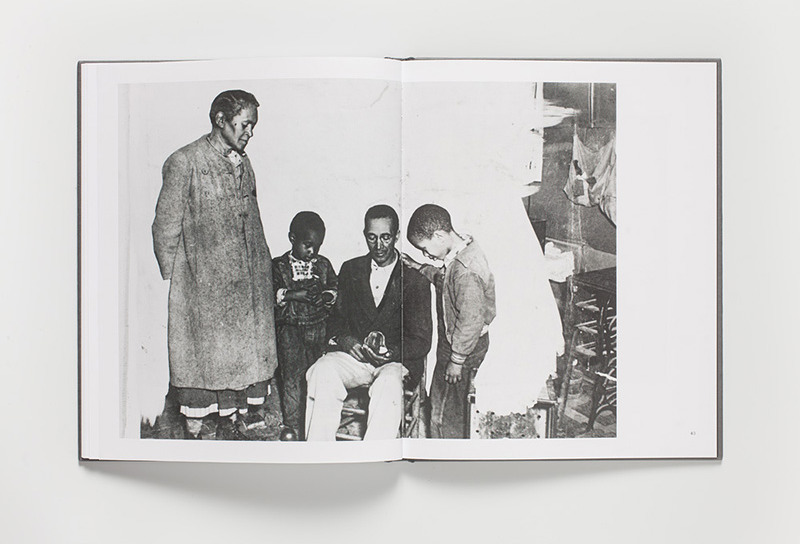

Often all that is needed as the starting point for an artist is one image, whether it comes in the form of a dream, something they witness on the street or a mark on a canvas. For Regine Petersen, it came through a rather obscure photograph: black and white; clearly American, clearly mid-twentieth century; a woman in a dress surrounded by two policemen, holding a rock. The image opens the first book (Stars Fell on Alabama) within this trio of stories, collectively titled Find a Fallen Star. Each story documents an instance of a meteorite falling on Earth, with the first documenting the first recorded instance of a meteorite hitting a human, taking place in Alabama on 30 November 1954. Taken at face value it feels like the work of melodrama, playing on themes of otherworldly disturbances, the decay of memory of time and, quite frankly, the mundanity of it. Nothing actually happens in Petersen’s work. Whatever was to happen has long since taken place. What we are left with are the fragments of events, which the artist has compiled, investigated, deciphered and meticulously arranged.

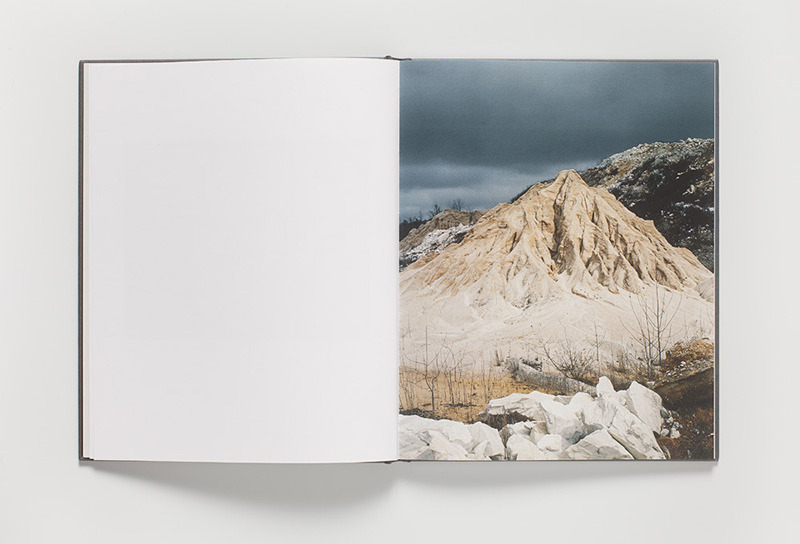

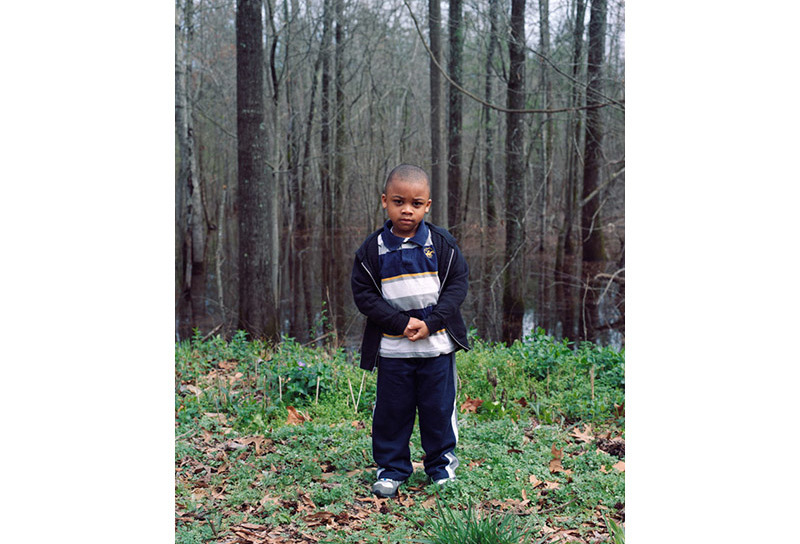

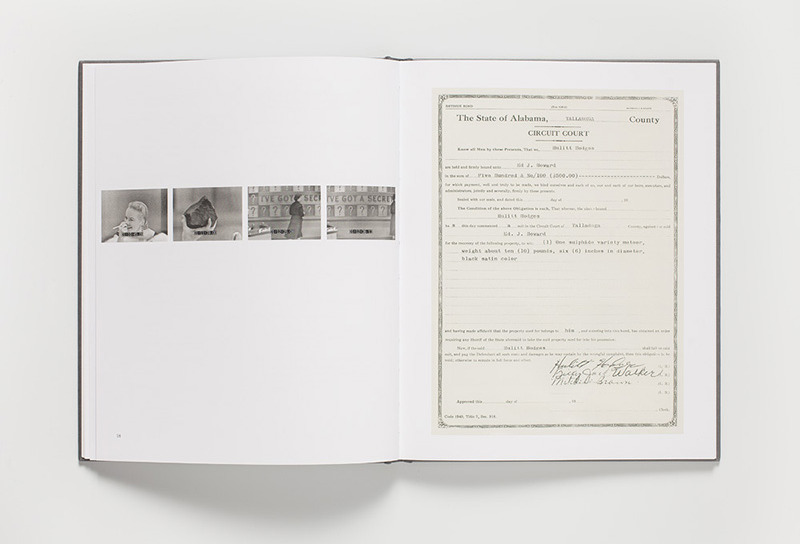

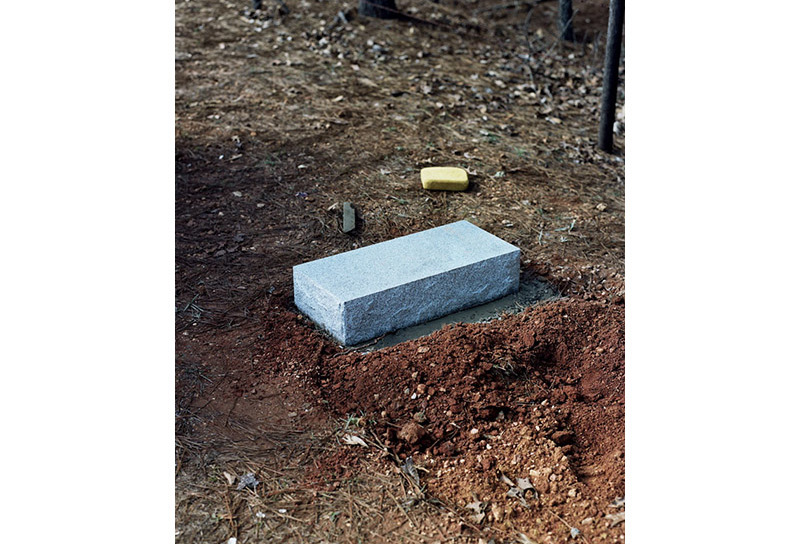

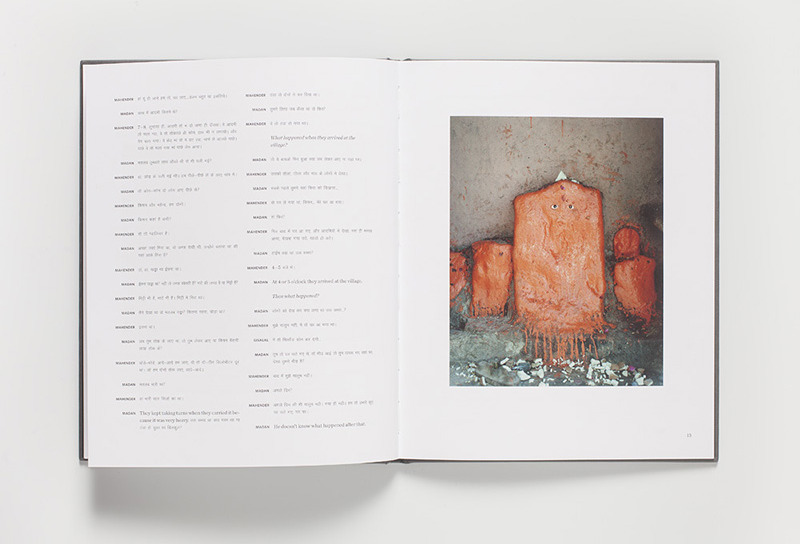

The locations of each event—Alabama, USA, 1954; Ramsdorf, West Germany, 1958; Kanvarpura, India, 1995—could not be more disparate, yet Petersen investigates each of the three narratives through a similar process. Formal documentation of the events (court papers, newspaper clippings—Google Earth makes an appearance) are intersected with her own photographs, ranging from striking portraits of the individuals closely involved, to scenes of ‘disturbance’—the ground slightly penetrated, an oddly placed rock, a suspicious mound of dirt. While each of the events that the artist explores have occurred on completely distinct locations on our planet, Petersen’s formulated and considered approach has formed a binding connection between all three. Beyond being associated through their odds-defying nature, each instance is embroidered with traces of religion, confrontation and the desire of individuals to claim part of ‘their’ rock (and with it, a part of history).

Throughout the books there is little consistency with regards to imagery (though by no means a flaw). We wade through the fragmented series of photographs and documents, as if detectives, attempting to reconstruct the events through evidence and unreliable accounts (the interview with Eugene Hodges, husband of the woman struck by the meteorite in Alabama, provides ample material as to how unreliable our own recollections of experiences can be). The process with which Petersen has selected and organised the content of the book could in some regard be considered academic in its approach; she does not attempt to define or marginalise anything, but instead seeks to find a balance between her own photographs that act as a retrospective documentation of the event and the more formal records that have served as ‘proof’ (another loaded term that Petersen, whether by intent or not, questions repeatedly through her work).

It is not possible to do true justice to Petersen’s project in just a few words, as the project is deeply complex and, in a way I rarely feel with works of this nature, incredibly satisfying. I was disappointed to miss the work when it was shown in Amsterdam as part of Unseen Photo Fair, but it is not hard to imagine the transition of the work from page to wall. What has been achieved with the book (a beautiful trio of hardback books, slipcase and booklet) is highly impressive, and it is hopefully just the start of good things for Petersen.