Studio Visit – Matthew Connors

Matthew Connors’ photography, exhibited in museums and galleries worldwide, has influenced younger contemporary photographers at length. Depicting a generation of protesters, he distanced himself from a straightforward documentary approach and created a new visual encyclopaedia of recurrences, portraits, symbols and simulacra. While this conversation gives us a chance to know him better, it also guides us to discover how creating a meaningful narrative is the result of an extensive, thorough research. Photographing, as well as editing and sequencing, are essential components of his working process. His studio is based in Bushwick, Brooklyn.

When did you start taking pictures? What led you to photography?

I gravitated to photography at an early age, for many of the same reasons teenagers of my generation did: an urgency to put something into the world, a fascination with cameras and darkrooms, and a crush on a girl. I was the kid in high school who spent a lot of time skateboarding and photographing his friends skateboarding. I grew up in a quintessential commuter town on Long Island and built a darkroom in my basement. My uncle had been an AP photographer and gave me his old equipment and taught me the fundamentals. I was 15 years old and became hooked. New York City loomed large in my imagination at that time and my early education in photography came from walking the streets of lower Manhattan, attempting to emulate the New Documents generation of photographers whose books lined my uncle’s shelves.

But I also know that you studied English literature. So how did you combine these two passions?

Not very well at first. I went to a school that didn’t have a strong art program and I was overwhelmed by the rigour of the school, and what little I seemed to understand about the world. I was in classes with people who had a much better high school education than I did, so I felt I needed to catch up and pushed photography aside for a while.

I ended up taking one photography class at the end of college. The course was taught by Laura Letinsky and it put me back on this path.

How long have you been working in this studio?

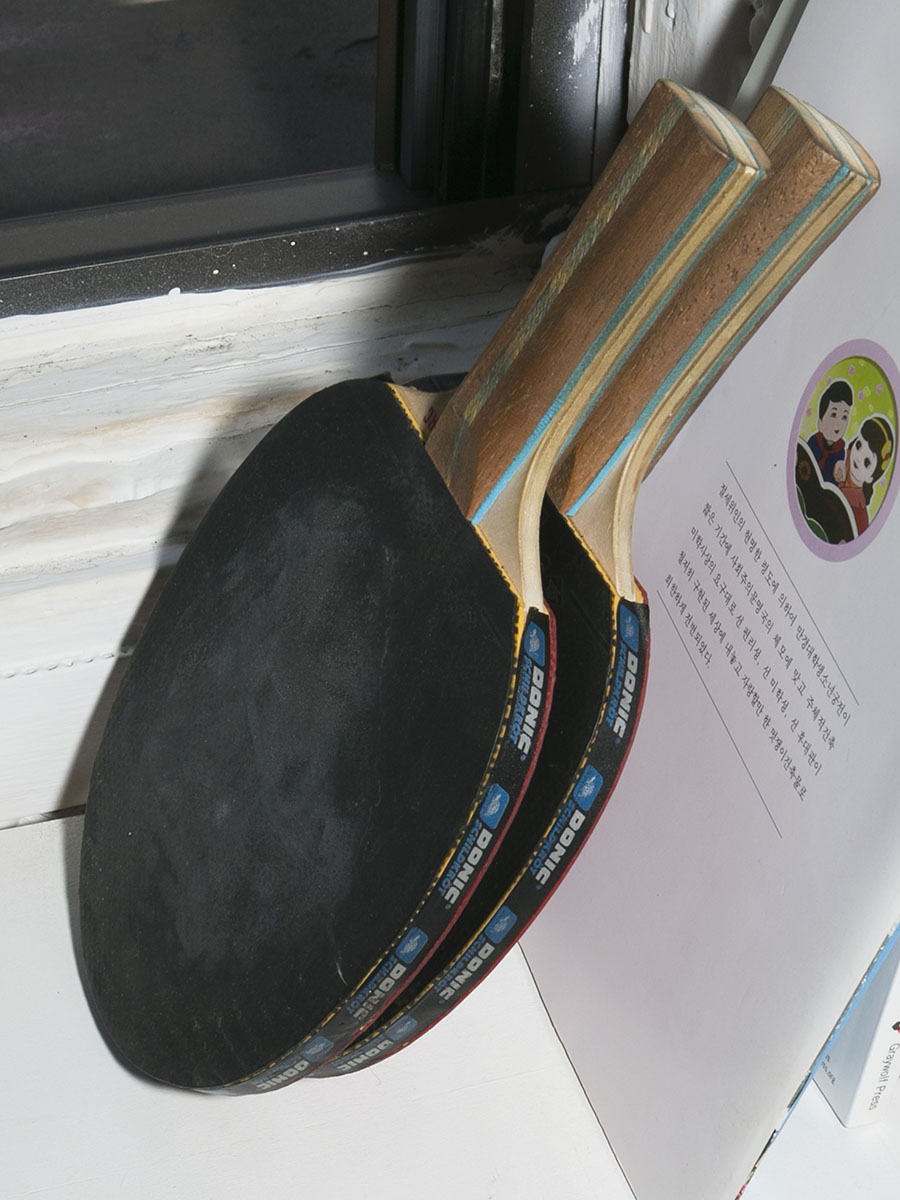

Not long. I moved in a few months ago. I was a bit of a nomad before. For years I had a studio down in Gowanus, which was nice. It was big enough to fit a ping pong table. It was a beautiful space that Penelope Umbrico handed down to me. But I was pushed out of that at the end of the lease. The owner decided to rent to commercial filmmakers instead of artists.

What led you to your current space?

This studio just came up. It was passed on to me from the brother-in-law of my best friend from junior high. I have not spoken to my friend in years but came across this space through our social media connection. Francis and I shared the space for a while. He decided to leave last month and I’m still here, settling in.

How is it going in this new space?

So far, so good. The challenge is finding time to be here.

That’s what I was wondering. You divide your time between Boston and New York and you also travel a lot to do your photography. When are you at the studio?

As much as possible, but mostly before deadlines. It really depends. I tend to travel a lot in the summer because that’s what my teaching schedule permits. During the school year I’m generally in Boston three days a week and in the studio three days a week.

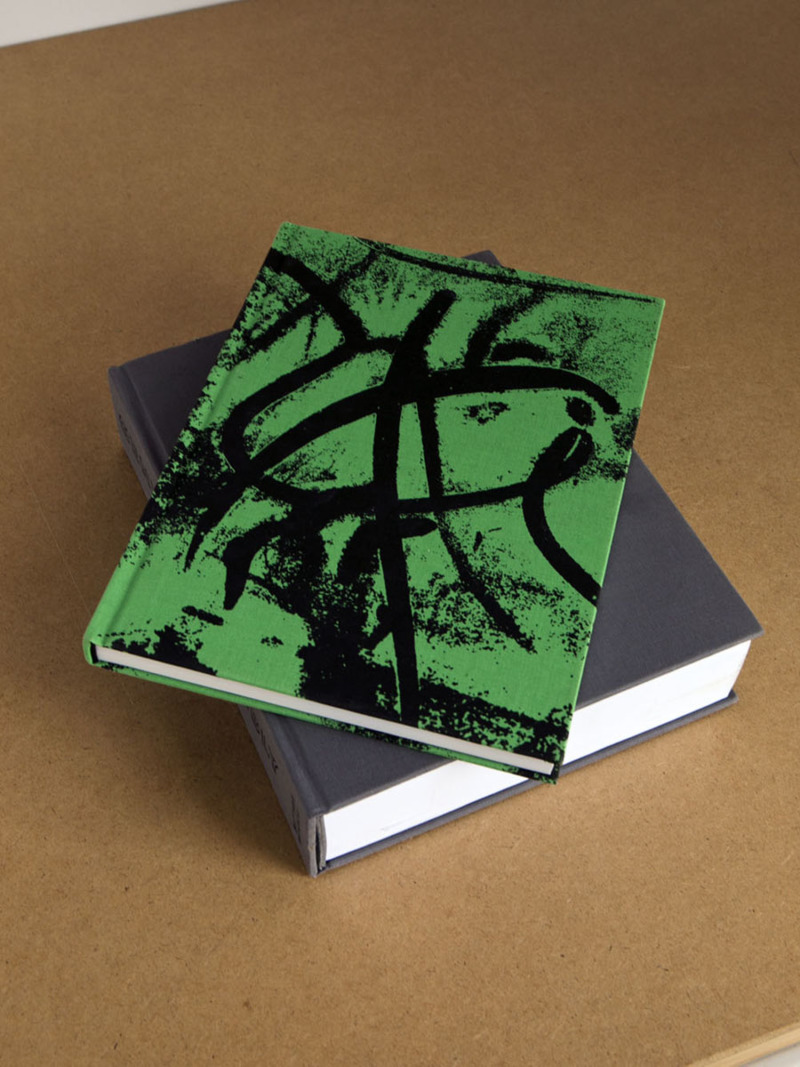

Talking about your work, you received a lot of recognition since 2015 when your first monograph Fire in Cairo was published. I’m interested to know how this has affected your practice or how you work today. Are you receiving more commissions or did you change your way of thinking about your work?

I don’t think it has changed the way I approach making work. In some ways it provided a template for how to assemble projects. Editing, sequencing, designing and publishing that book was quite an experience and helped me to think about how to deal with my work going forward.

Was the editing a long process because of the quantity?

Yes, a lot of it was due to the volume of pictures. I came back from Egypt with roughly 20,000 photographs. I spent a lot of time culling pictures, sifting through images and cutting out things that didn’t work. It’s a lot of trial and error, and it can be really complicated to find the right constellation of pictures to give shape to a project.

When you travelled to Egypt or when you’re travelling to other places, do you go with one idea and eventually change it while you’re there? How does the place inform you and make you shift direction in a project?

Well, when I travelled to Egypt, I didn’t fully know what I was going to do there.

I think of Fire in Cairo as historical fiction more than activism. It was important for me to signal that in the form of the book, because of the complexity of the situation in Egypt and my relationship to it.

What drove you there?

A lot of that came out of my experiences with the Occupy Movement, and photographing it for a year straight. During that process, I met Egyptian activists who were part of the original 18 day uprising in Tahrir Square. After Mubarak stepped down, the Supreme Council of Armed Forces took control over Egypt. There was a lot of friction between the SCAF and protesters. Some activists felt it was not a safe time to be in Egypt and came to America to speak about their experiences. That’s when I met some of them in Zuccotti Park.

So it’s more personal encounters that led you to Cairo…

Yes, it was that and I had been following the news about the revolution in Egypt closely. It was influencing the way I was thinking about events here and perhaps what needed to be done on the ground in America.

You’re often involved in all of these protest experiences. Is this a way for you to be more active?

Partially. My work is often aligned with the aspirations of protest movements, but I’m not actively propelling them forward as much as the true activists and organizers are. I’m not comfortable calling myself an activist, because I know many who put so much more of their time, energy, and effort into organizing than I do. I think of Fire in Cairo as historical fiction more than activism. It was important for me to signal that in the form of the book, because of the complexity of the situation in Egypt and my relationship to it.

I also read somewhere that you were thinking about making a Protest Trilogy. Is this something you’re still thinking about?

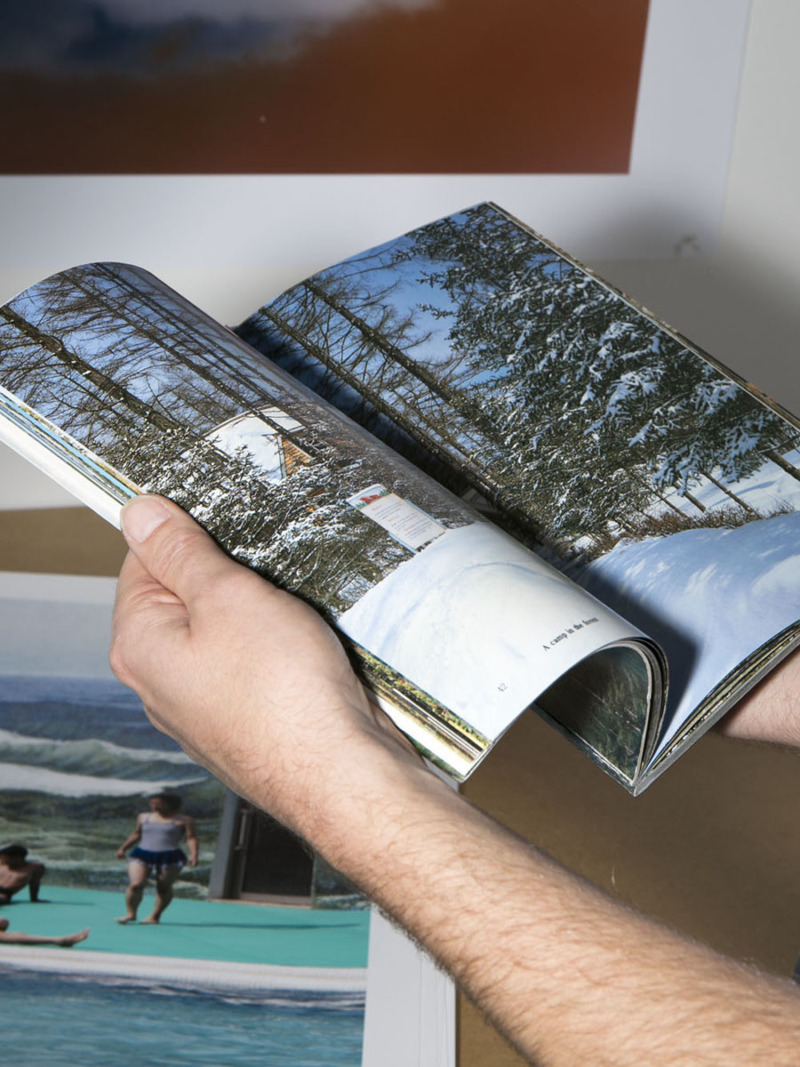

Yes, but I don’t know what the third instalment is yet. I originally thought the work I’ve been making in North Korea might be a candidate, but now see it as a separate endeavour. If I ever do a trilogy, I think I will need to find another idiom for the third book, another way of working. General Assembly is fairly direct in terms of being a collection of portraits. The reason why the book is so big is because I felt compelled to include everyone I photographed; about 650 people. I wanted the book to echo the spirit of radical inclusion that fuelled the early days of Occupy. The book tries to embody the tension between the collective and the individual. Fire in Cairo is very different. It’s more elusive, but connects to General Assembly through my approach to portraiture.

And so did you self-publish General Assembly?

No, that’s a handmade book. There are only two copies of it, I made all the prints and then had it bound professionally. I spoke to some publishers about it, but the length of the book proved to be a budgetary challenge. I did not want to make an expensive book about income inequality.

I have a slow metabolism, and spend a lot of time thinking about photographs in relation to one another, and ordered sequentially. I’ve become very interested in the breath of possibilities, accessibility, and growing dialog around photobooks.

Talking about one of your earlier series, Tenuous Republic, it seems we’re witnesses of accidents happening in all of these images. Could you tell us more about this project and how that series came together?

In some ways that series was driven by process. I started making those pictures in the early 2000s, when the technology of photography was transitioning to digital and I became interested in an increased flexibility of the medium. I started revisiting an early interest in street photography in a more methodical way. I’d stake out locations and photograph in one spot for a duration of time, sometimes hours, collecting glimpses of drama and poetic gestures of people moving through a chosen space. I’d later composite together fragments of negatives from the same location shoot, compressing different moments into a single, credible picture.

I have sketches I can show you. I call these “sketches” because I used them to figure out what parts of the negatives to use. You can see some pictures have multiple versions, or outtakes. With some of these pictures it took a lot of time to decide what the final version might be. There were some years when I made only 10 images, which was a little frustrating. I worked on this project for seven years and spent some of the best years of my life playing with Photoshop. But there’s something about these pictures…

There’s this feeling of suspension that you kept reiterating throughout all your works. Probably General Assembly stood out differently but I can see there’s wonder; as viewers we don’t understand what’s happening. Another, maybe more aesthetic element, is your shift to photographing vertically in your recent works. How did that happen?

Yeah, that was a change. I think a lot has to do with a shift in preoccupation with making photographs for walls to making photographs for the pages of books. I think about both, but my imagination is now more calibrated to books.

What influenced you to move towards this? Is it being surrounded by so many publications? Or how we approach visual language today? Is social media somehow influencing this shift?

Not quite. Some of my pictures are timely and could exist on all those platforms, but they are also in some ways out of date. Many of the pictures I take are related to events or moments in history that journalists cover, but I am much slower at putting my images into the world and am not trying to depict newsworthy moments. I have a slow metabolism, and spend a lot of time thinking about photographs in relation to one another, and ordered sequentially. I’ve become very interested in the breath of possibilities, accessibility, and growing dialog around photobooks.

When I look at these pictures, I feel like you’re always trying to show how people get affected on a deeper level. I think about the political situation, but what emerges is the inner fear of people, this constant tension of being threatened. So sometimes you may forget what’s happening and see the more psychological consequences of what’s happening.

Yes, I think about that a lot. I think about how nation states and structures of power influence our day to day experiences.

It might be interesting to see how we are affected too in this moment in America..

Yes, we have been thrust into a dark moment. I can’t say I’m completely despondent, but for the first time in my life I’ve been listening to reggae music, and I never really liked reggae, but it has been making me feel better.

I have a lot of friends that have been having Trump dreams. I should start recording these. I’ve always struggled to remember my own dreams, but the dreams I’ve been told about are classic anxiety dreams: someone taking a shower in the White House and looking for a towel on the upper floors and realising the only place where she could find one was Donald Trump’s bedroom, and being terrified to go in there. Another one was about someone going to the White House for a meeting with Trump in which he was showing off his long white fingernails and all he could talk about is how great his manicure was. There’s something deeply disturbing about the way he has infiltrated our subconscious.

Would you like to show us or tell us more about Cuba and North Korea?

I can show you some prints from North Korea, I’ve been there three times in the past three years. I don’t have any prints from Cuba yet.

Do you feel this is a completed project right now?

I’m still figuring this out, digesting the images. My thinking about the images is evolving. I’m still discovering the motifs. There are material things that are happening too in terms of manipulating the pictures. I spend a lot of time in the studio fixing problems with pictures. When they are not quite working, I try to think of another way they can.

Did you have any problems while you were there?

Not many. I had to delete pictures on some occasions, and endured some tense moments. It’s a very managed experience. I had handlers at all times watching me and determining the rules of engagement. Overall they wanted me to have a good experience in their country and opened up to me in some surprising ways.

So are you editing this work right now? Can you tell us more about the process? I’ve seen you editing before and I really enjoyed seeing it. I can see you have a lot of piles there.

It took me a year to edit the work from Cairo and my publisher became a bit irritated with me in the process because I am slow, terribly slow. I always feel a lot of urgency to make the work, but somewhat less to put it into the world. I just suspect it will fall into place at some point.

And so what about Cuba? When did you start going there?

That happened mostly by chance, I went there the first time in 2015 with Andrianna Campbell. We wanted to collaborate on something and ended up doing a piece for Frieze magazine. We were thinking a lot about monumentality in Cuba. Many monuments there are very idiosyncratic and localised but also in various states of disrepair, which seemed like an apt metaphor for the state of revolutionary ideals and Cuba right now. I went back again in 2016. That body of work is evolving as well.

Is there some photographer, partner, artist that is a source of inspiration for you?

I have several friends who help me shape my thinking about my work. Nicholas Muellner is someone whose opinion has been critical for me at certain points. He has a new book out now that is very moving.

We haven’t talked about you being a teacher and inspiring other people. Is this something you want to keep doing?

I was very lucky to get my job at MassArt. It’s a long story, and I didn’t think I would be there as long as I have been, still commuting between New York and Boston. When I started I thought I would be teaching for one semester, but am now finishing up my 13th year. My plan just before starting was to move to Los Angeles.

Why Los Angeles?

I have good friends there and have always felt a different sense of freedom when I visit. I grew up 20 miles from where I live in Brooklyn and I still feel like there is some psychological baggage for me in this geography.

So is this still in the back of your mind?

I’m thinking about it but I don’t know. All signs are pointing towards leaving New York. It can be limiting here. My life is held in a delicate balance by surprisingly reasonable rents right now, but it seems inevitable that it will go away. And when it does, I don’t know if I’ll stay here. I’ve been in my apartment now for 17 years and I’ve seen a lot of changes I’m not particularly excited about.

But I still enjoy teaching at MassArt. It’s a truly special school. It’s the only publicly-funded, freestanding art college in the country. The tuition is a fraction of what private art colleges charge. Our students are not entitled, and work very hard. Art can be incredibly empowering for them and that is a beautiful thing to witness. I would be sad to leave the community completely, though I do often wish I could teach a little less and spend more time photographing.

Photographs by Cassidy Araiza