Studio Visit: Stephen Gill

It’s hard to find a photographer quite so synonymous with London as Stephen Gill. Now, after over a decade of working in the heart of the East End and producing some of the era’s most iconic projects, the creator of Hackney Wick has decided to relocate to Sweden. During a quick six-day trip back to London, Gill invited us into his studio-cum-archive to talk about his practice, his books and what he plans to do in Scandinavia.

How long have you been in this studio space?

I’ve been in this studio for three years or so. Prior to that I was a mile down the road in a place called the Greenheath Centre on Three Colts Lane, which, like many of those big buildings, ended up getting converted into liveable space. So unfortunately I left there because they were converting it into residential spaces, but it was an incredible nine years there. I made so much work in this tiny little space.

Was it much smaller than this?

Much smaller, though just as dense. Because it was an active studio, where this is more like an archive now, there was a much more alive feeling to it which I loved. Also it was a time when I didn’t have a family and had less obligations in that sense, so I was just there, all the time, to the point where I ended up sleeping there even if there’s no kitchen, but I just washed in the swimming pool. But I did that for years; even now looking back, when I think of that building, I tend to think of the work I made whilst being there and the work that passes through these tiny little spaces really.

How important has having a studio been to making your work?

I remember firstly having the studio in 3 Colts Lane and of course it’s wonderful because this is a place where you make work, you think, you go there on a daily basis. Even on days when I didn’t make work I went there just to think. I like that there’s a separate space to process and think. But there was a time, in the early days of having a studio, when I thought to myself that when I was in it, it was a bad sign because I would much rather be outside making work where a lot of my early work was made. Only more recently has my work been a mix of studio-bound and walking and cycling. I suppose for ten years so much of my work was made by leaving the studio. It was just going into the studio, early mornings, maybe answering some emails and then by sort of 6.30 a.m. I’d leave again to make work and not check emails or take telephone calls. I try to keep the two things very separate.

How much time of your time is split between your studio and going out to make work?

Earlier on the percentage was definitely 90 per cent out making work, 10 per cent in the studio. The process of making work is very important to me and I try to spend as little time as possible sitting at a computer. I strive for that because I feel there’s a danger that you get in a situation where you make work and then, sadly, the more work and books you end up making, these things trail behind you for ever it seems, so that’s something I’m beginning to learn to try and grapple with. You know, you could make a series in 1999 or a book in 2004 but you still get emails today because people are always seeing things for the first time, so for you, your head isn’t there anymore and you’re not even that person anymore, but at the same time it’s still trickling behind you. I think that is a bit of an anchor sometimes and I’m always tempted to completely cut it. There are times when I do get worried and that’s something I never thought about when I first started making work; you leave this trail of stuff behind and it’s always just these few steps behind you.

If you hadn’t had other people here working with you, do you think you would have been able to go on with it?

The help was absolutely vital. It was key really as this kind of thing will just force you into an admin position. I do know friends who are photographers who don’t even have time to make work anymore because they’re so busy writing emails about their practice and sending images to people that in itself can derail you.

I guess that becomes more and more of a problem as you go on.

It is, yes, and you can end up offending a lot of people. I try to do as many visiting lectures and interviews as possible, but very often in order to protect my practice, I have to say no, and therefore I end up almost upsetting people. It’s a little bit of a fine line and there’s no wrong or right way. If I have time and energy of course I will try to do things. I think much of my momentum and discipline and pressure upon myself was purely internal because I love making work and purely making it for myself. But more recently I’ve not just had the internal pressures but also external pressures of requests, so sometimes it’s a little bit too much.

You said it used to be spent 90 per cent out making work, 10 per cent in the studio. Has that changed now that your practice has shifted a bit? I think of projects like Coexistence and Talking to Ants; I guess they are more studio-based projects compared to your work before.

That’s a really good point. I think that Hackney Flowers was probably a balance between the two because I was on my bicycle making pictures, sourcing pictures, but the great thing about that is that even in the studio, it was lots of this manual intervention and digital processes, so it was still working with my hands and I’ve tried to latch onto that with quite a tight grip. Even with Coexistence it was knitting together work that I was doing outside with different types of cameras and taking water samples with buckets of water, but it was a strange multi-layered series. Much of it, what I call ‘base pictures’ that were C-types, were almost starting points, and then I would rephotograph those a second time with some little manual interventions or the pond water itself; I would take back those very pieces of paper and reimmerse them and rephotograph them, so some of those pictures were sort of three or four generations in. So you’re right, I was kind of dancing between the studio and the geographical parameters of the subject.

That leads on to a question that I was sort of going to save for later but it seems right to ask it now. Why is it so important to you that you touch everything that you make? Is it because it’s so personal?

I can’t pinpoint it to anything. I really enjoy the tangible process of making something. Often it’s also not just the feeling of touch, I think it’s that it’s the touch linked to something – almost a frame of mind, kind of tuning or diving in. Sometimes I see it as almost a visual extraction where you’re not just using a camera to describe; it’s almost this extraction of what a place feels like and therefore I think the hands probably play a big part in that because you’re aiding the subject and that might mean the burying or collecting or the sourcing of objects. It’s an interesting observation, I haven’t really thought about that before.

I was looking through your work and thinking that what you’ve made most recently is sort of these collections and gatherings of things, like your Off Ground project where you went around and picked up the bricks from the London riots, bringing them back then into the studio. Even though those images were so simple they had gone through such a history of extraction and touch.

Maybe part of it is just aiding the chosen subject. In the case of those bricks, you’re sort of helping them speak for themselves but in order to do so I’ve pulled them out of where they were found. I like this idea of, as the author, taking steps backwards to allow the subject to takes step forwards. I really like this thought, partly because photography is so much about control, and I like these slippages of control and a conscious stepping back. It’s strange that something does happen, and I think even in the case of the series Talking to Ants, where I’m adding things to the camera, even though there’s a distortion or lack of information, even a lack of clarity, there is something that manages to get through that filter that I’ve put in the way. For some reason it feels closer to what often a very straight, descriptive picture can emit. I just find it amazing that certain things can creep through when you deny information or clarity or sharpness. It’s weird what does manage to get through and sometimes it’s more than ample.

I get that. It makes me think of one of the images in the Talking to Ants series; there’s a gravestone with an angel on it that’s just out of focus, as if you’d taken a step back from focusing the camera. The feelings slipping through are so much more intense than it would have been had the image been, like you say, descriptive.

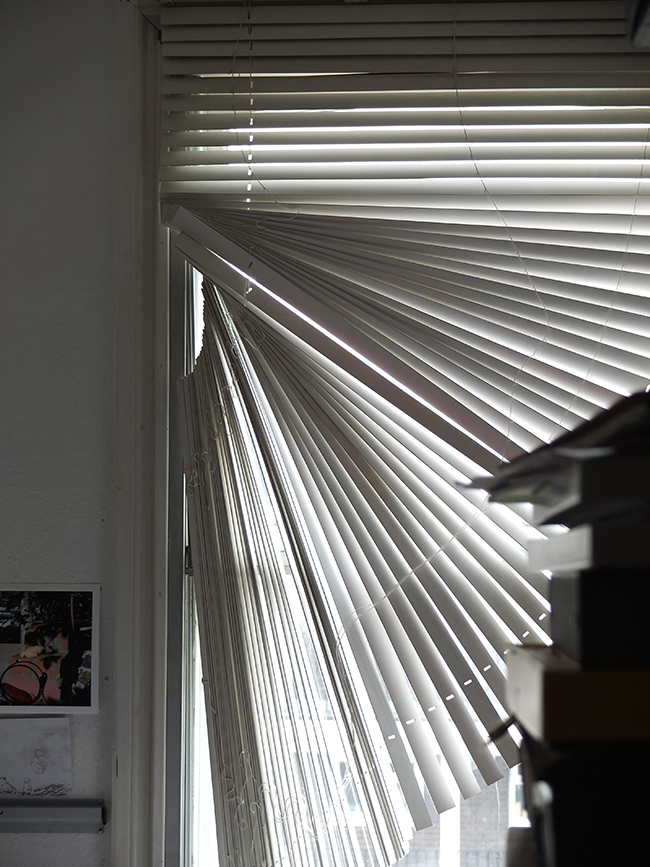

I think that’s true, because you’re not distracted with detail. I think I started to learn this in 2001 to 2005 when I was working on the Hackney Wick series. It was then that I became so excited by this lack of information in a time when we were bombarded with information and clarity. Pictures were packed and I always thought we were amplifying and enhancing, but I like the idea of thinking, ‘Is it possible to deny information, but then retain a kind of weight?’ When I made the Coming Up For Air series I was very much in that frame of mind. I was deliberately overexposing and making pictures almost like you’re squinting. So I think that was a language that I was really trying to tap into and I felt that was very relevant for some reason.

Do you think that was a way of going against what contemporary photography was doing at the time?

In a way it was. With photography you’re often trying to describe the times we live in with such high clarity. I suppose I didn’t try to describe so much as try to have the subject creep through. A lot of those works were the first time I’d actually tried making photographic responses to the times we live in as opposed to photographic descriptions. I really think that was the big shift for me. My earlier works like the billboard series and these sort of comparative studies were very descriptive and detached, and the new work was more of a really strong reaction to the times we lived in, but didn’t necessarily pinpoint one thing. For instance, with the Coming Up For Air series, the pictures were actually made in Japan but I would say that that is absolutely not a body of work about Japan. If anything it’s a response to my life in London at that time and more of a reaction to the chaos and muting feeling of being in London, kind of like when you swim and your head is under the water.

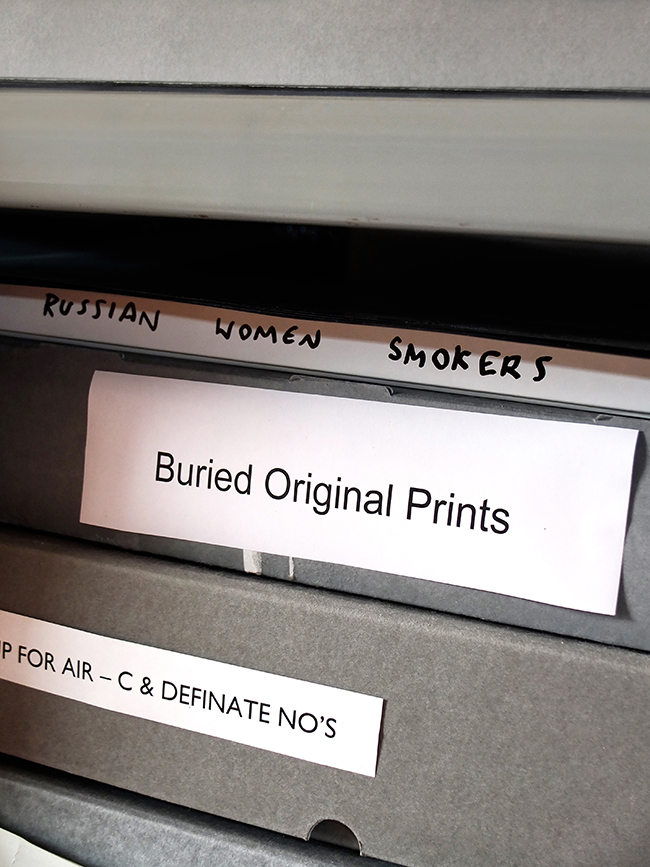

Do you think being surrounded by such an expansive archive has given birth to projects in and of itself? Your book B Sides immediately springs to mind.

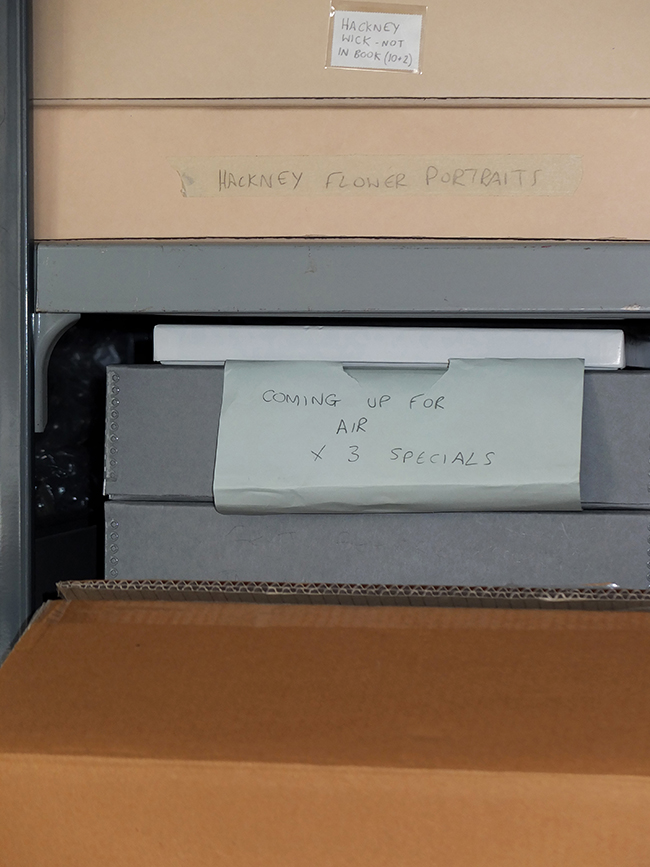

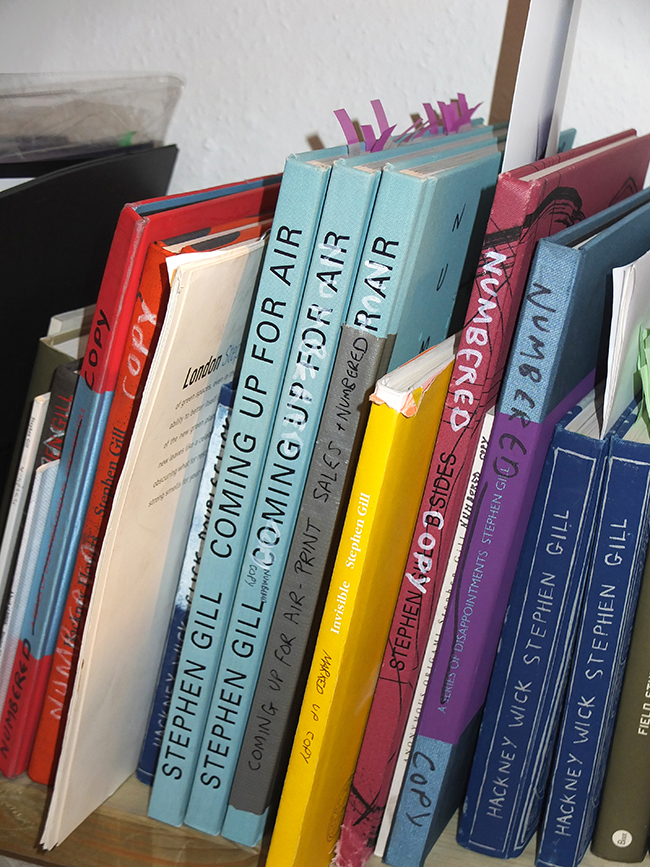

Not really. It’s strange, because I’m one of those people that, as much as I like to protect the work I’ve done and archive and number it and so on, I’m also not very good at looking backwards. When I get older I probably will start opening these boxes again, but I rarely do. B Sides, weirdly, was a book that was a companion to Coming Up For Air, but in a way I look at it as one of those strange bodies of work that almost made and assembled itself. These are pictures I just didn’t want to let go of. They made so much sense to me but for some reason jarred or just didn’t allow themselves to go into the Coming Up For Air book, so they were all sort of cast aside. Looking at them as a group it just made sense, and in the future I didn’t want to make a new edition of Coming Up For Air with some new added pictures, revised and updated. I absolutely wanted to stand by these pictures now and didn’t see them as some sort of afterthought. In some way I almost prefer B Sides because it feels a lot more relaxed than Coming Up For Air, which had so much effort put into its edit and is much more complex, but B Sides sort of assembled itself and I think you can feel that in a way.

I can understand that. I think, like in music, an album of B sides that didn’t quite make the cut, makes just as much sense as the finished album.

Maybe it’s that suffocating of the things we love and knowing when to stop. I think you can kill a series of pictures if you keep chipping away. I’m very aware of that when I’m editing pictures. I have these sort of set rules: firstly, I never edit on a computer screen, I always work with hand prints. I always have piles of edit A, edit B, edit C, and they sort of dance between each other. I work that way when sequencing and I look at them and live with them. I may come into the studio one morning and just remove a picture and suddenly you feel the series go up a notch. But then I’m aware that you can look at things too much and you can kill them, like listening to your favourite record too much or eating your favourite food. We can absolutely kill the things we love by too much exposure to them.

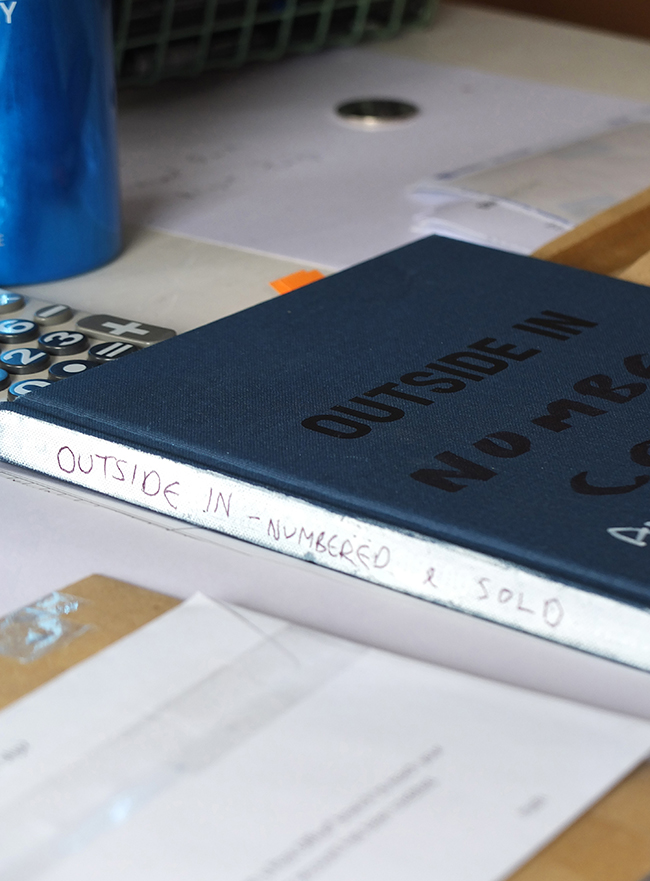

I want to talk briefly about your books. I guess that main thing I want to ask is, why are your books published by Nobody?

In 2005 I decided I wanted to publish a book of photographs called Invisible, which was a book of mostly service men and women in fluorescent clothing, based on this idea that it was originally designed to make people more visible but, in my mind, had the opposite effect. I really wanted to assemble and make the book myself, and was definitely going to do that. Someone asked me, ‘Who have you got lined up to publish it?’ and then the name ‘Nobody’ was born out of probably replying ,‘Nobody’, and it became a sort of joke. Then I just kept it. It’s a little bit silly, but it’s just stayed for nearly ten years now.

I think it’s quite interesting that now with photo books, you have people buying them solely because it’s the next book by whatever publisher, and not looking or even caring who the photographer is. So with Nobody, it’s almost the opposite as it’s nobody publishing it. Do you think the publisher’s name now carries as much, if not more weight, than the work itself?

I don’t really know if that’s where it’s at, but I have felt in the past few years this hype where someone at the top of the cultural pyramid says, ‘This is a great book,’ and then everyone rushes out and gets it, but I don’t know if people even look at it to decide whether or not it’s great for themselves. I don’t think people decide so much for themselves anymore, which makes me a bit sad. I think we’re being told what’s good, rather than deciding what’s good.

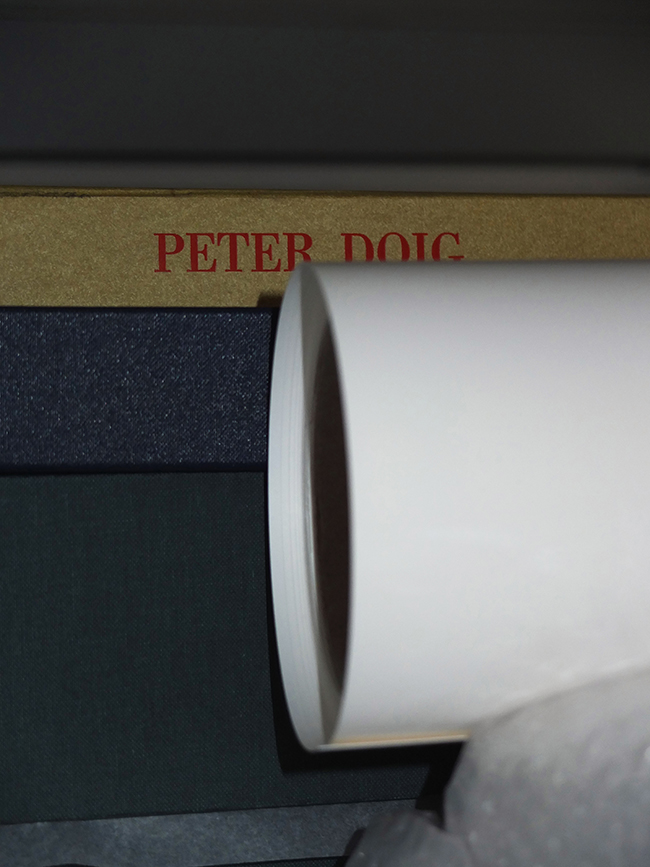

I know you’re an avid book collector yourself. Do you have any favourites?

It’s incredibly hard to pick. Most of them are now over in Sweden so I haven’t got them to look at. I’d definitely say Michael Schmidt’s Waffenruhe, Fukase’s Ravens as well. Most of the ones I’m thinking of are black and white weirdly.

What brought about your decision to move to Sweden?

It was various things really. Firstly, my partner is Swedish and our kids are half Swedish, so Sweden has always been there. Secondly, the kind of London squeeze. It’s difficult to be a non-commercial practitioner of any cultural type and to stay afloat. So it’s a protection of the work in a way, a protection of my health as well. I had a bit of a burnout last year and was in bad shape after this 20-year run of seven days a week, obsessive behavior, so it was a bit of a wake-up call really. Sweden ticked a few boxes really, and I’m also really excited about the change. I never imaged I would do something like that, especially because I love London so I feel slightly like I’m turning my back on this place. But we’ll see where Sweden takes me and where it carries my work.

Do you plan on making work there now then, or do you plan on coming back to London to make work?

I don’t plan on coming back to make work. I’m sure I will feel compelled to from time to time, and there’s still things bubbling away in my head that I would love to do here and haven’t executed. That said, I feel quite excited and inspired in Sweden, but God knows how it’s going to carry the work. It’s like starting from zero really, slamming on the brakes.