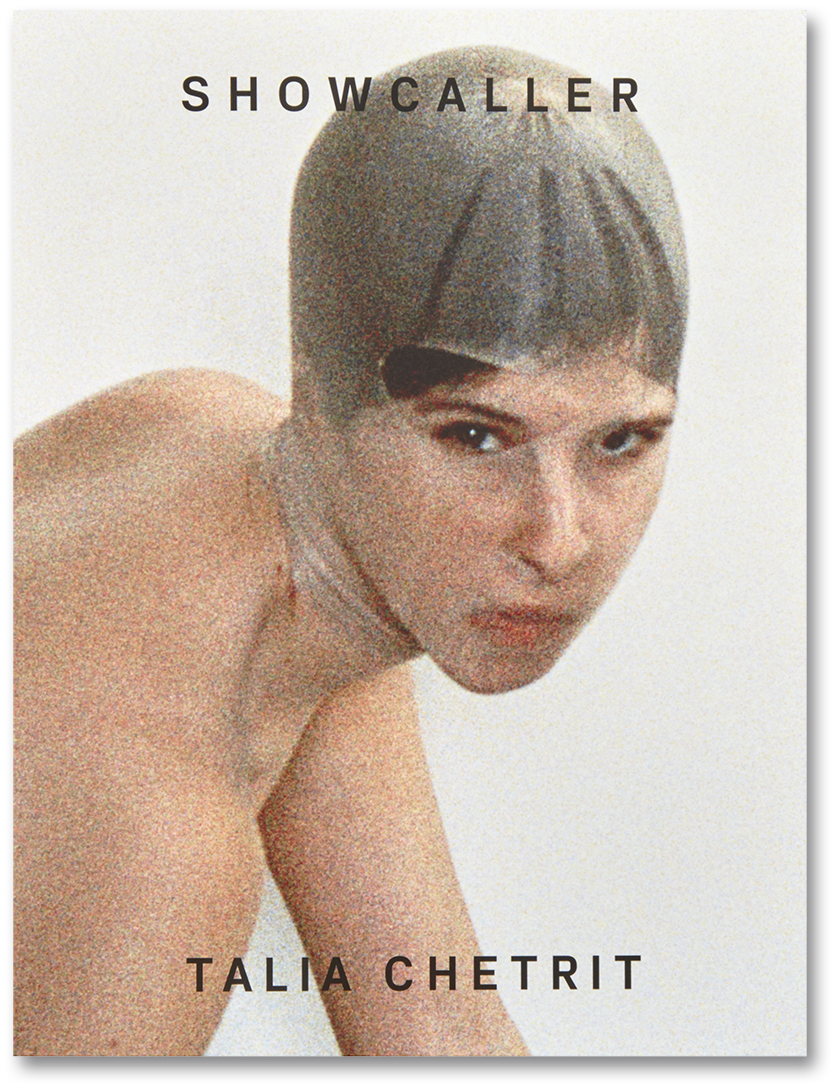

Talia Chetrit – Showcaller

Traditionally, books have been used to bring order to artists’ scattered fragmentary practices. Their inked and bound pages place limitations on what can be included. Together an editor and artist must work through a series of questions: What is worth keeping? What looks good? What will sell? What do these pictures say? It’s clear that in moving through this process, which already involves two minds, no book can ever encompass its creator. There are always details that escape, pictures that don’t make the cut, and all books are late – by the time they are printed they are already outdated. At every point there are gaps, missing pieces of a puzzle; can we rely on these to make our names?

Talia Chetrit’s first book Showcaller (MACK, 2019), collects together over twenty years of photographic work, the earliest from 1994 when she first picked up a camera aged just thirteen; the latest from 2018, the year she held a retrospective exhibition at the Kölnischer Kunstverein, Germany. Showcaller attempts an intractable task, it establishes Chetrit as an artist but at the same time, it offers criticism of singular, knowable identities. It plays with the presence and absence of the photographer while it presents an artist who has had to find ways of accommodating herself, personally and professionally, to the shifting field of photography – a field which has changed more dramatically in the past twenty-five years than at any point in its previous history.

Anyone who has lived through this change will recognise the same. There has been a breakdown in visual privacy; photographs are more likely to be made without our knowledge or permission, at the same time we must be aware of the ways in which we photographically construct ourselves, and we face the fact that our image is diluted amongst many others. This new politics of photography is captured succinctly by Sahra Motalebi’s essay sitting alongside Chetrit’s images, “Any of our phones holds private directories of our workplaces, family, enemies, parties, items for sale online, other artist’s work, but also, possibly, of our genitalia, and those of others.”

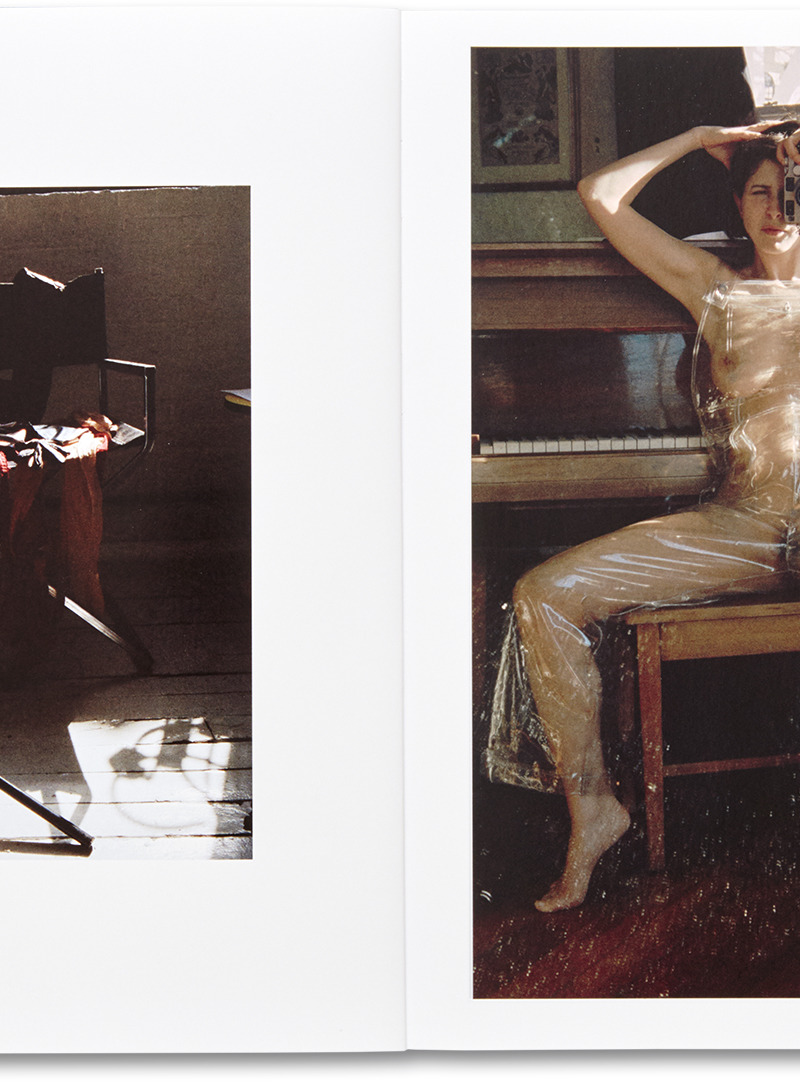

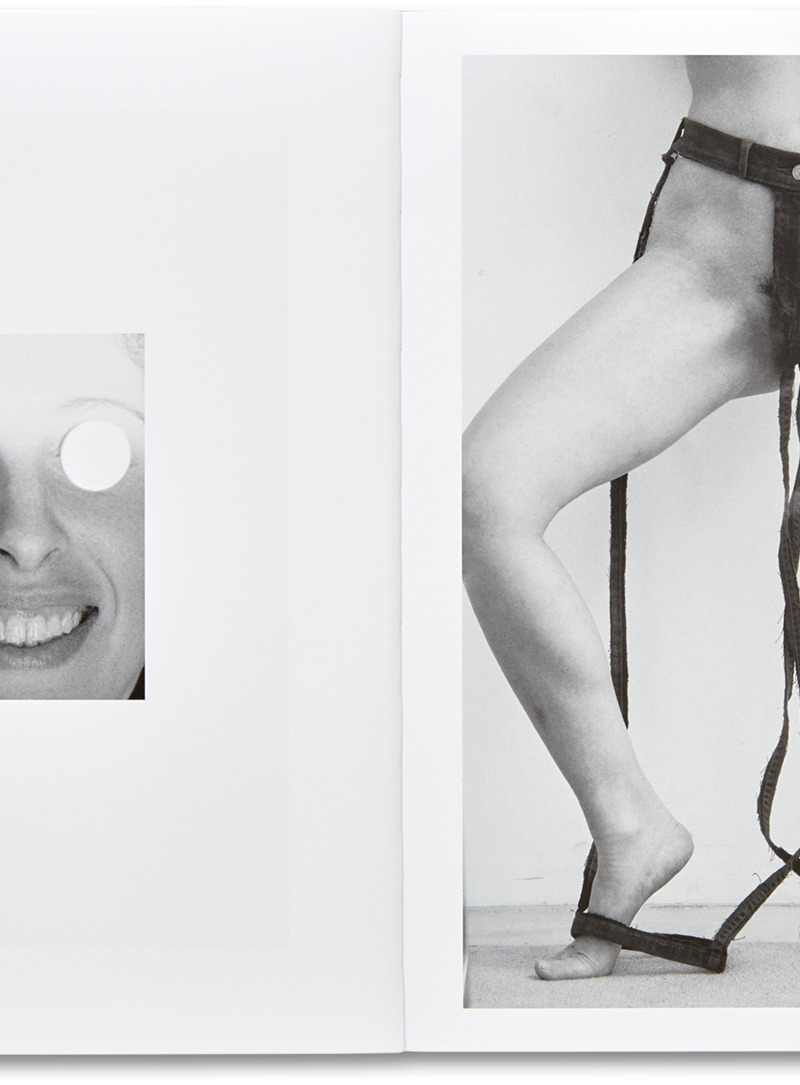

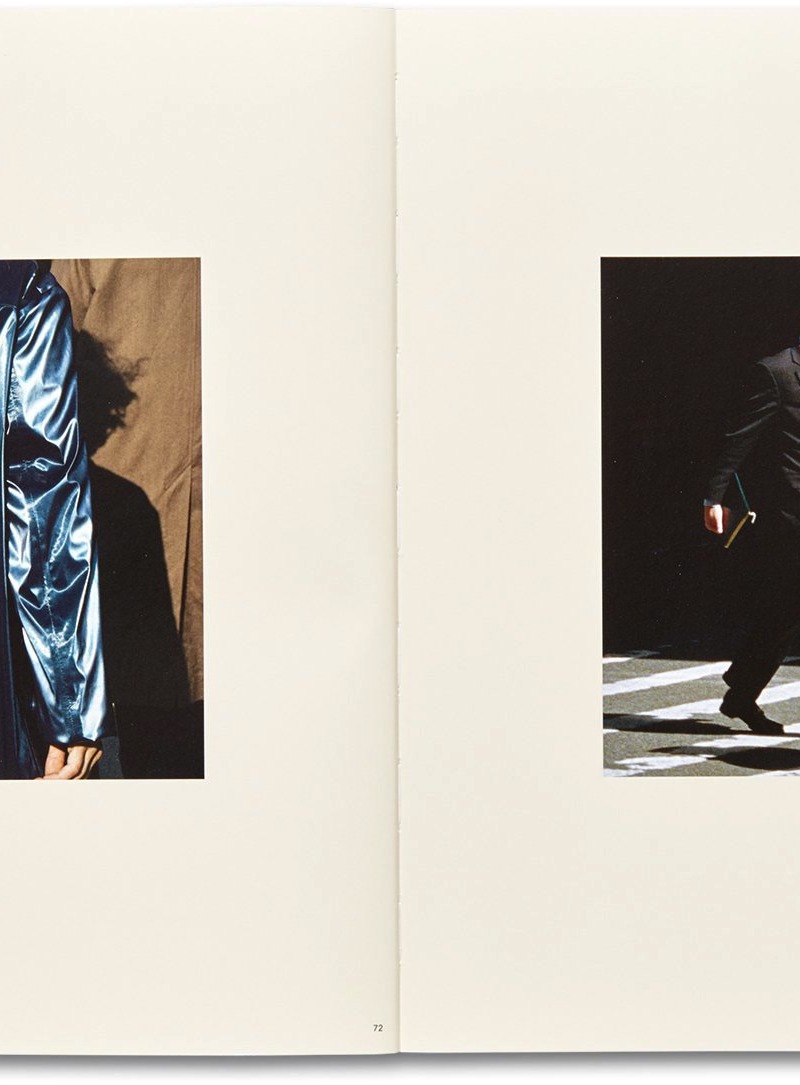

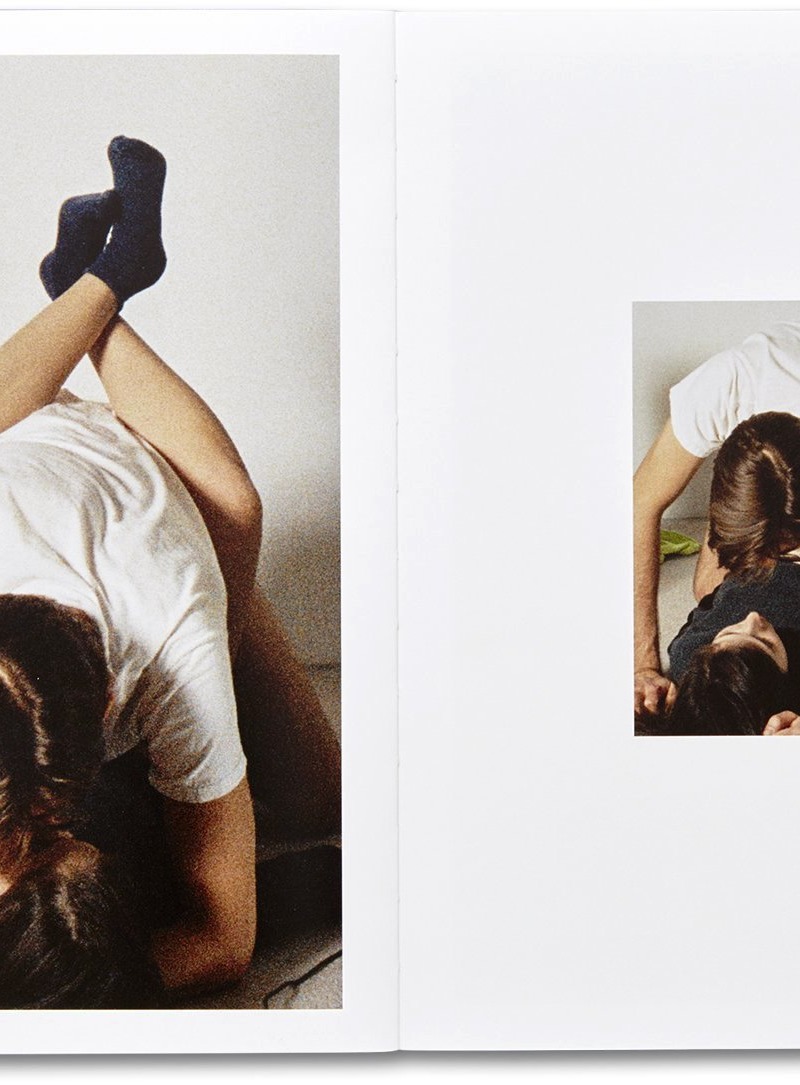

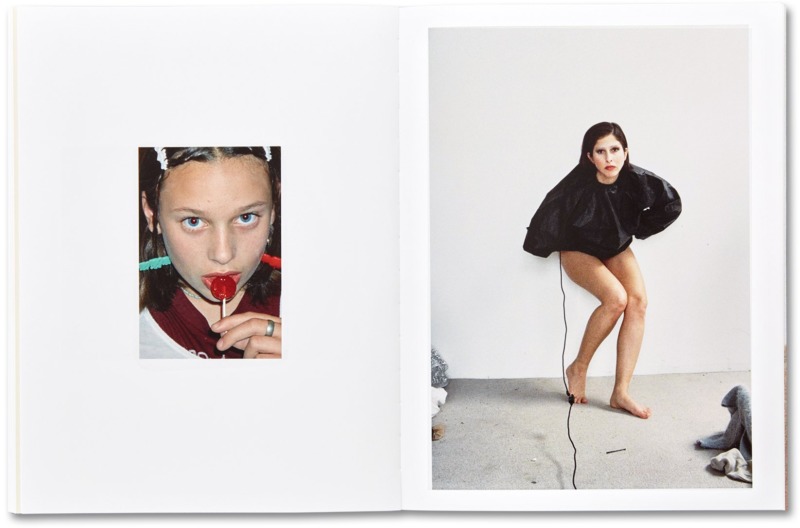

Chetrit seems to revel in these casual, vernacular uses of photography, particularly the self-portrait. Many of these pictures are clearly staged, while others suggest they have been found, appropriated, and incorporated into her body of work. The earliest pictures in the book show herself playing with the camera as a young teenager. Later the pictures take an erotic turn; she sits nude in the studio, she clothes herself in transparent PVC, indulges in exposure, standing naked in a field in the midst of sexual embrace. Between these she shows a voyeuristic tendency, photographing strangers through a long-lens camera through the window of a New York office tower. In others she plays the part of a bloodied murder victim, slumped, clutching her wounded stomach.

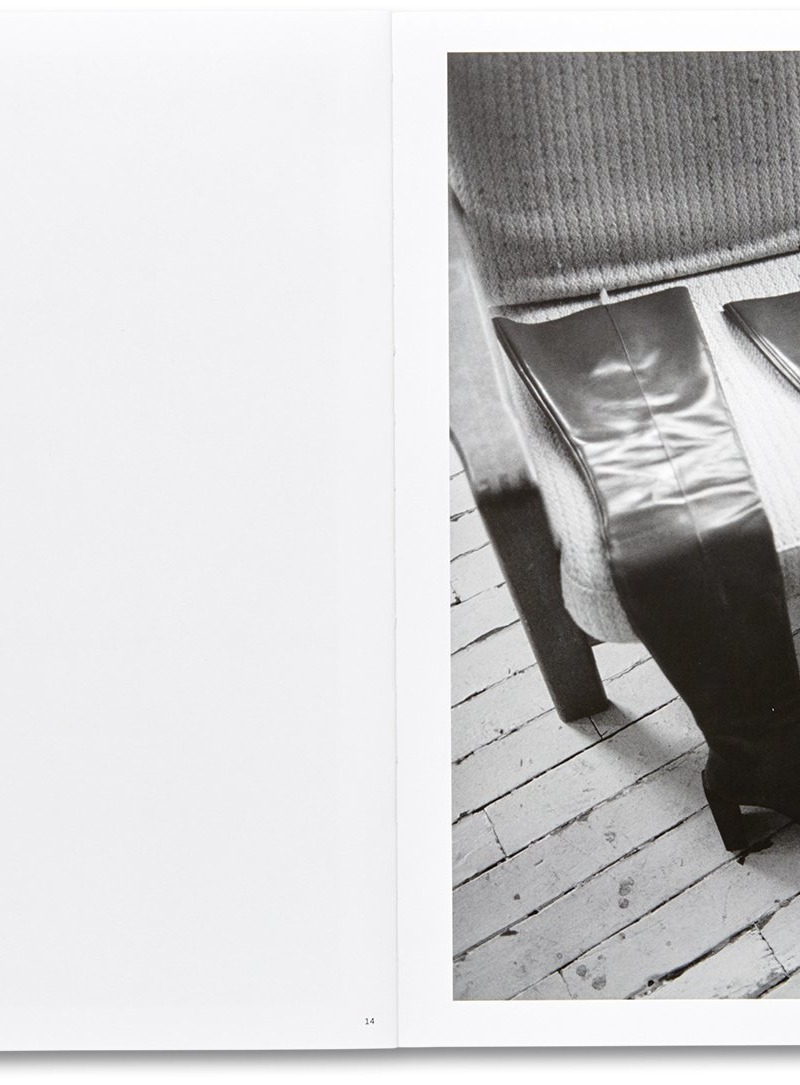

“Despite her self-exposure”, Motablebi writes, “Talia is obscenely hard to pin down on and off stage. Oddly ambivalent about being the focus of her work, it is not an invitation to know her, as the subject, per se. In fact, she knowingly refracts and disarticulates her own subjectivity, her face and voice, her very involvement in her photos and video works.” Throughout Showcaller, Chetrit’s body is rarely whole, more often cut by mirrors and surfaces that divide, reflect, and duplicate. Objects displace her – a bike seat, a vase, and thigh-high latex boots take their turns in front of the camera – cold parodies of her intimate self-portraits. In some pictures, the camera is taken out of her hands, the decisive moment of exposure given over to a partner who holds the shutter trigger. Every time I feel something approaching a person coalescing, every time I see a picture which could be used to say who Chetrit is, she becomes something else.

In a way, books present a similar incompleteness, they are nothing without a reader, but the act of reading provisionally alters the books. Reading isn’t the passive acceptance of information, it’s creative, it has to be. I have to fill in the gaps with imagination, drawing on references, experiences, and meaning outside of the text in front of me. I fall back on habits, gestures, rehearsed movements and sayings. Her nudes bring to mind L’Origine du monde, the photography of Nan Goldin and Janice Guy, or perhaps just a nameless ex. However it happens, memories of Chetrit’s photographs become scattered amongst these other memories. They rub up against one another, they pass things on. There’s no end to this process, reading and looking always implicate another.

Showcaller is a book that encourages imagination, it demands an attention to the details and references, but engages a mind able to wander. It’s a similar quality to the suspension of disbelief in theatre. In fact Showcaller takes its title from theatre – being named after the person whose role it is to manage the stage from the moment the curtains raise to the moment they drop – to keep the show running. It’s a book that keeps up a pretence. It takes on multiple historic roles of photographers while suggesting no sense of progression. It’s a retrospective book that doesn’t restrict itself to a chronology, theme, or style. It’s a book that, while it condenses a life’s work into a single document, doesn’t try to lock down a single, coherent identity.

I find Showcaller provokes and evades questions of Chetrit’s identity, but as I’ve reiterated, it is never limited to Chetrit; this is a book that points to people beyond its pages. Through her use of models, through her illusions, through references to known images and a wider set of photographic vernacular, the scope is broadened. This question of identity and intention goes further than a single artist, it calls in question the entire field of photography. When our identities aren’t our own, when we make them through images, putting them beyond our control, self-knowledge is limited. How can we know ourselves? These are the contradictory, unsatisfactory grounds on which we must make our names – at least, this is how I see it.

All spreads courtesy MACK, all images © Talia Chetrit