Tom Callemin – Index

There is, so we’re told, a seemingly endless proliferation of photographs in the world; less often mentioned, though, is the fact that many of these pictures appear to function in the same way. Most are used descriptively, that is, they point to the existence of events or objects in the world, showing them as they were at the moment in which the picture was made. There is, of course, nothing simple about how this translation from moment to picture occurs, but in terms of what the vast majority of photographs actually do, we seem content for the most part to take their ‘descriptive’ role at face-value. By contrast, Tom Callemin in his series Index, employs a stark, almost forensic style of picture-making that he nonetheless uses to upset the legibility of his subjects, so that the resulting images, although they are perhaps easy enough to ‘read,’ take on the lucid particularity of a bad dream.

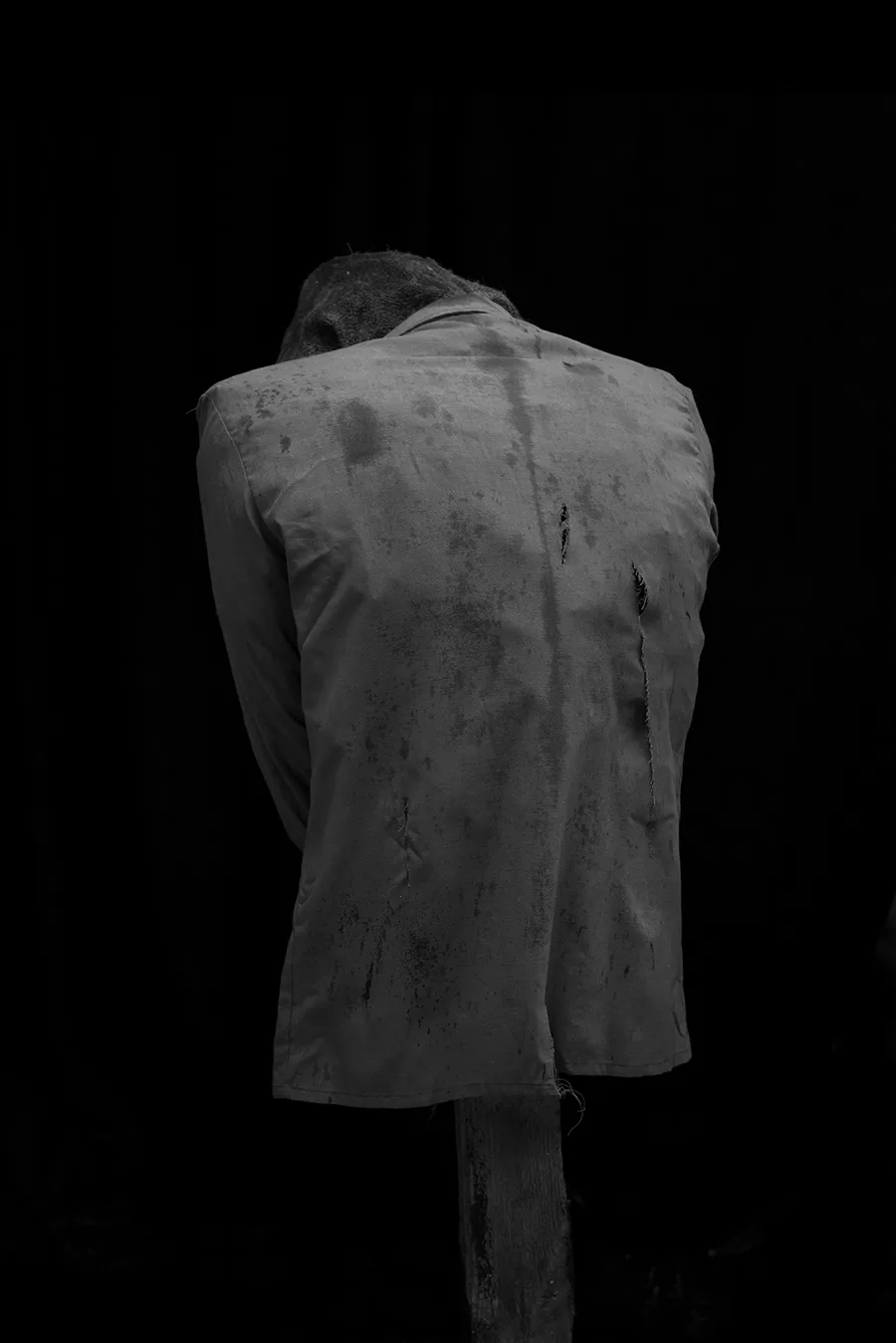

The vocabulary of the images is a familiar one, or at least seems so initially, coming from a whole range of photographic uses that tend to fall outside the arena of art photography as it is conventionally understood, but which actually makes up the bulk of photographic imagery in circulation. Such photographs exist for a definite purpose, they explain or demonstrate, functioning as diagrams, essentially, but with the added clarity and descriptive capacity of a photograph – consider, for example, the documentation of accidents and crime-scenes that Callemin’s work so effortlessly resembles. Drawing on this flotsam of informational picture-making, the kind that can readily be found in encyclopaedias, manuals, and numerous other sources, he has hit on a notable vehicle for both reflections on what certain kinds of imagery can do, and what the specific content of these pictures might reveal, suitably manipulated. It seems to have opened up a world of unsettling possibility, one that is all the more effective for being parsed in these familiar terms.

The pictures hint at more elaborate narratives, something that is happening just beyond the edge of frame, but won’t resolve exactly what that might be

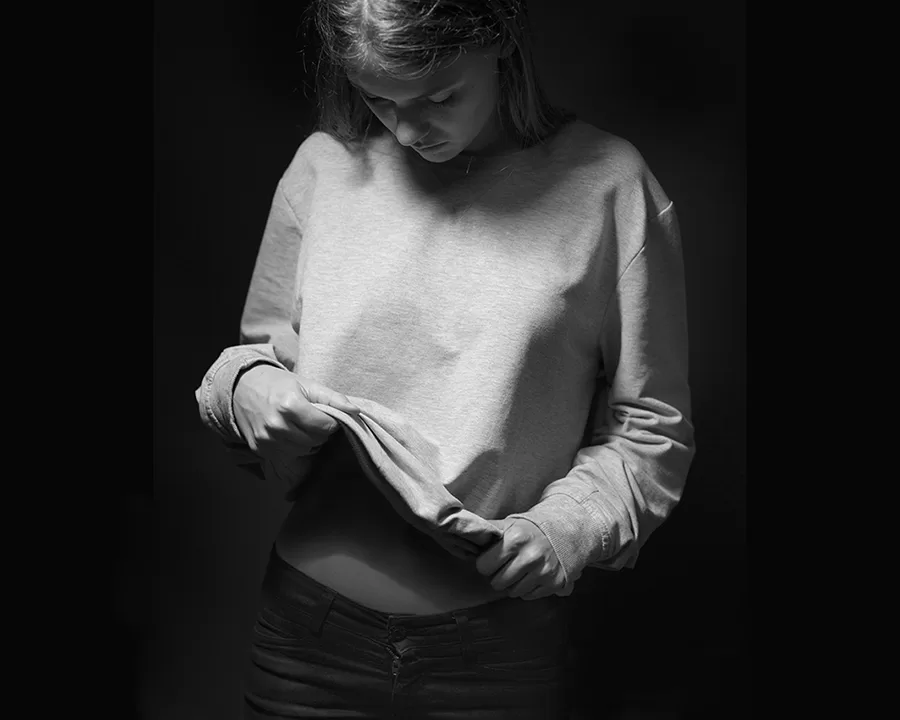

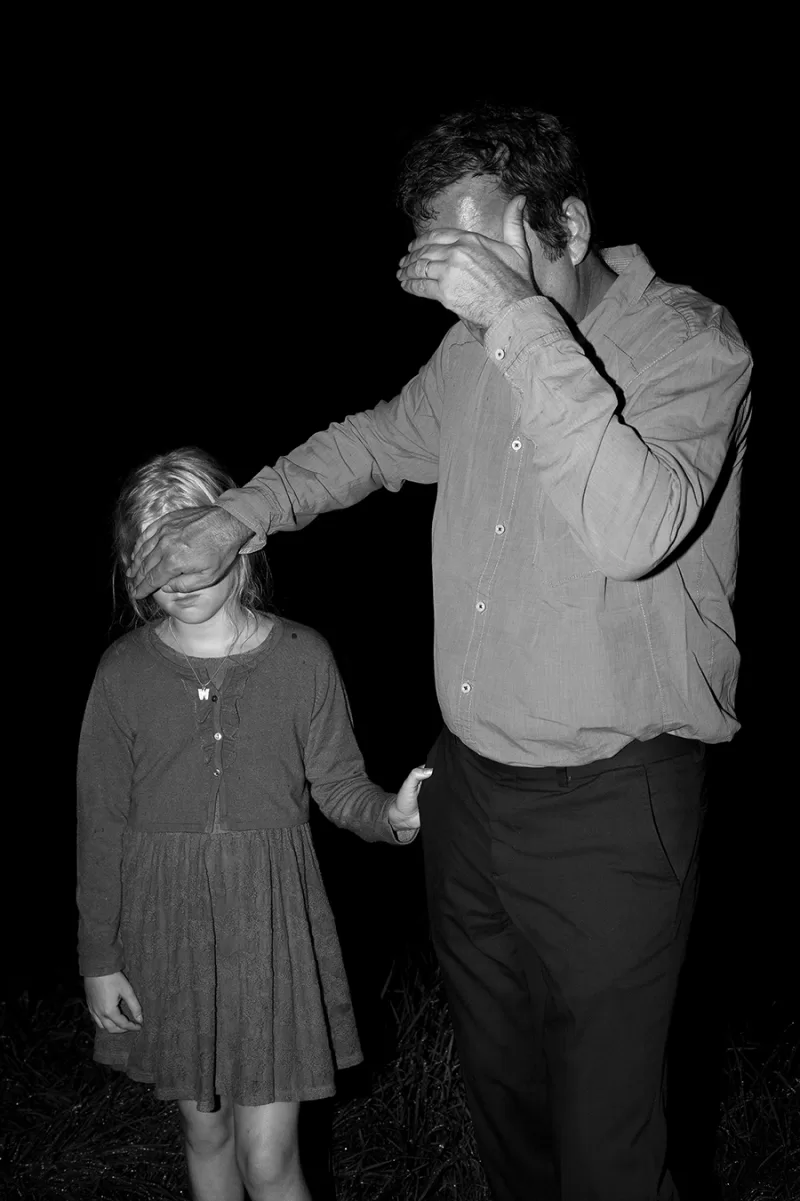

It is a notable property of photography as a medium, however, that when pushed to extremes its defining qualities tend to have an uncanny, alienating effect. Indeed, Callemin’s work is a good example of how photographic visibility is essentially a paradox: no matter how ‘transparent’ the picture, the subject isn’t really there, we are only seeing a trace of it in the picture – and a ‘constructed’ one at that. Callemin makes very telling use of the resulting play between presence and absence. The pictures hint at more elaborate narratives, something that is happening just beyond the edge of frame, but won’t resolve exactly what that might be, so the tension between what can be seen in the image and what can be understood from it is, essentially, the engine of this work, which rests, then, on a kind of productive refusal.

As a title, Index alludes to the idea that photographs are a particular kind of sign, a distinct product of the technology used to produce them; in short, it suggests that the photograph is a direct tracing of an object or moment, like something fossilised. At the same time, it brings us back to the notion of descriptive photography and its uses, an indexing of the visible, notionally to make it ordered and comprehensible, having some connection to the grand taxonomies of the 19th Century, such as natural history museums and collections of oddities. But the dual resonance of the word in this case also points to something ambiguous and unresolved in the duties that we assign to photography in its (supposed) capacity to make visible. By stripping these ostensibly functional images of any kind of contextual information, such as might be used to ground of their suggestive prompting, Callemin exposes the insufficiency of photography as a descriptive tool, while still using this putative shortcoming as a means of making images that convey a kind of double-edged meaning – or rather, potential meanings – that the viewer can explore.

Just as important is the kind of stilted, frozen atmosphere that the pictures evoke. All photographs are, of course, immobile, in some way; that is characteristic of the medium. But the sense of arrested motion that Callemin favours here, facilitated by the use of strong flash-lighting in most of the images, is of a different order again, being a far more self-conscious choice and one that calls our attention back to the machinery of the pictures, along with their origins in a particular stylistic vocabulary. It is more than a simple ‘effect,’ however. The rhetorical impact of this style and Callemin’s use of it here, making for an atmosphere of barely restrained, but unspecified menace, (taken, somewhat perversely, from the reassuringly ‘expert’ tone of informational photographic sources), suggests how even supposedly neutral forms of image-making are inflected with the concerns of the historical context in which they are made. It doesn’t take much of a shift to bring these latent energies to the surface and they are that much more powerful, precisely because of how they contrast with this sense of visual restraint.

If Callemin’s work is not so entirely specific as to be a compendium of present-day fears, it is at least mapping where they can (and do) emerge. He has been able to mine these fears and give them a distinct visual form, without being obliged to state exactly what they are.

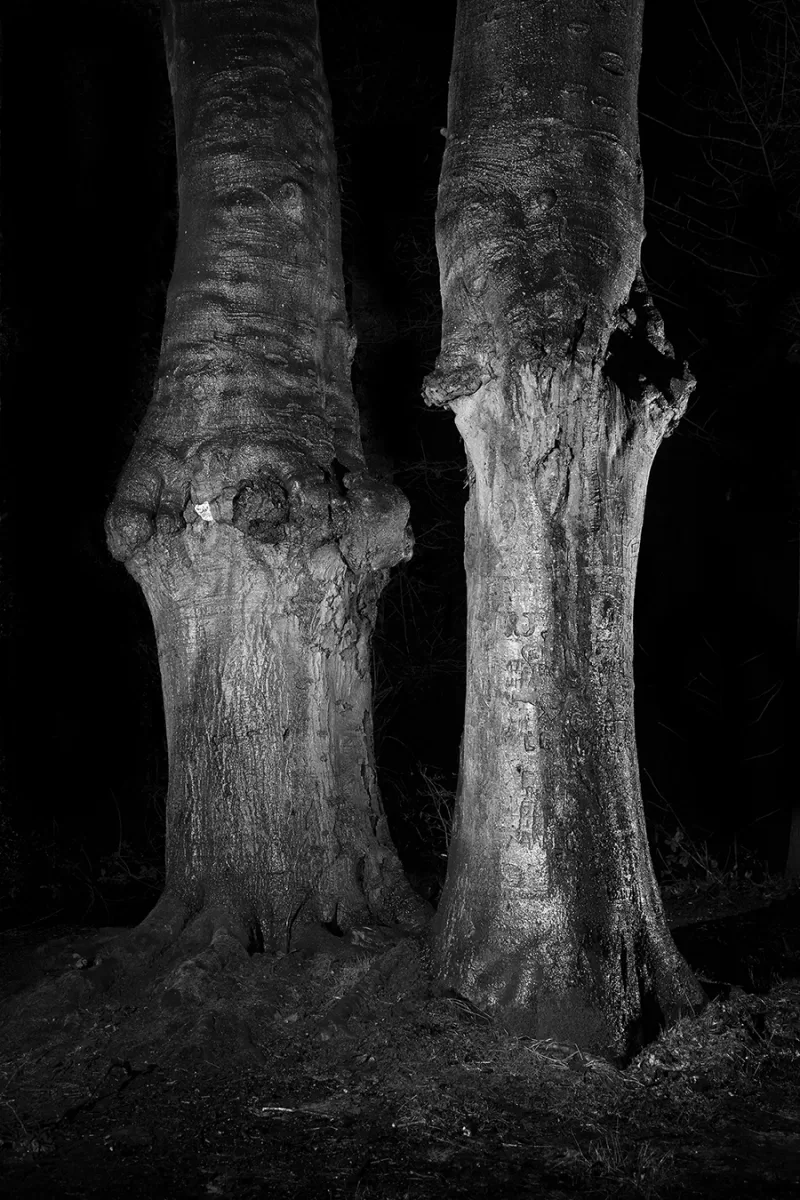

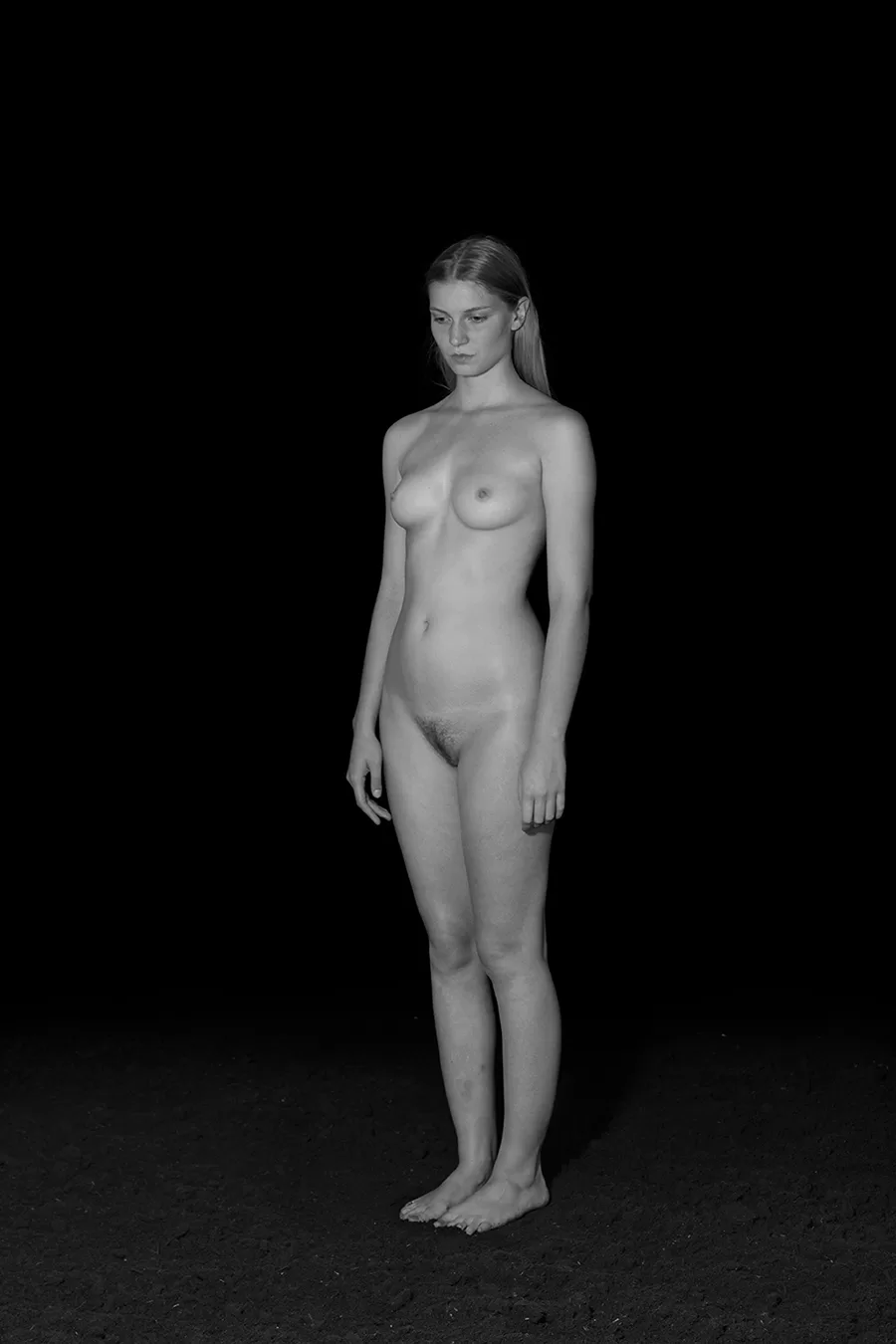

There is, equally, a sort of continuity to what the pictures are actually of, enough to make an argument for a thematic unity that isn’t a ‘narrative’ exactly (in many ways, this seems to have been deliberately removed from the pictures) but that is nonetheless sufficient to deduce an over-riding preoccupation with disaster, aggression and human frailty. In that respect the work takes on a kind of ‘science fiction’ aspect, though it is one that, in common with the most advanced examples of the genre, uses a demotic form to somewhat ruthlessly probe the deepest points of contemporary anxiety. We have, then, bulging tree trunks that suggest ecological catastrophe linked to destroyed or abandoned structures and a hazmat suit carefully stretched out in what looks very much like someone’s living room. Similarly, a female nude, nearly anonymous in its perfection, appears as a potential future subject of this brave new world – almost everyone else seems to avert their gaze, blinded or horrified by events just outside our field of vision.

The ‘future’ is often a projection of the unconscious or suppressed anxieties we are living with right now. If Callemin’s work is not so entirely specific as to be a compendium of present-day fears, it is at least mapping where they can (and do) emerge. He has been able to mine these fears and give them a distinct visual form, without being obliged to state exactly what they are. This is not at all distinct from the pictorial vocabulary that being employed, which tends to reinforce a particular reading of the images, despite appearing somehow beyond style itself. The mix of thematic intensity with a seemingly affectless telling, in which charged encounters rise spectre-like from the surrounding darkness, is a potent one. Taken together, these images add up to a world of illogic and displaced meaning that still seems entirely, if somewhat frighteningly, plausible.