Vytautas Kumza – Half empty half full

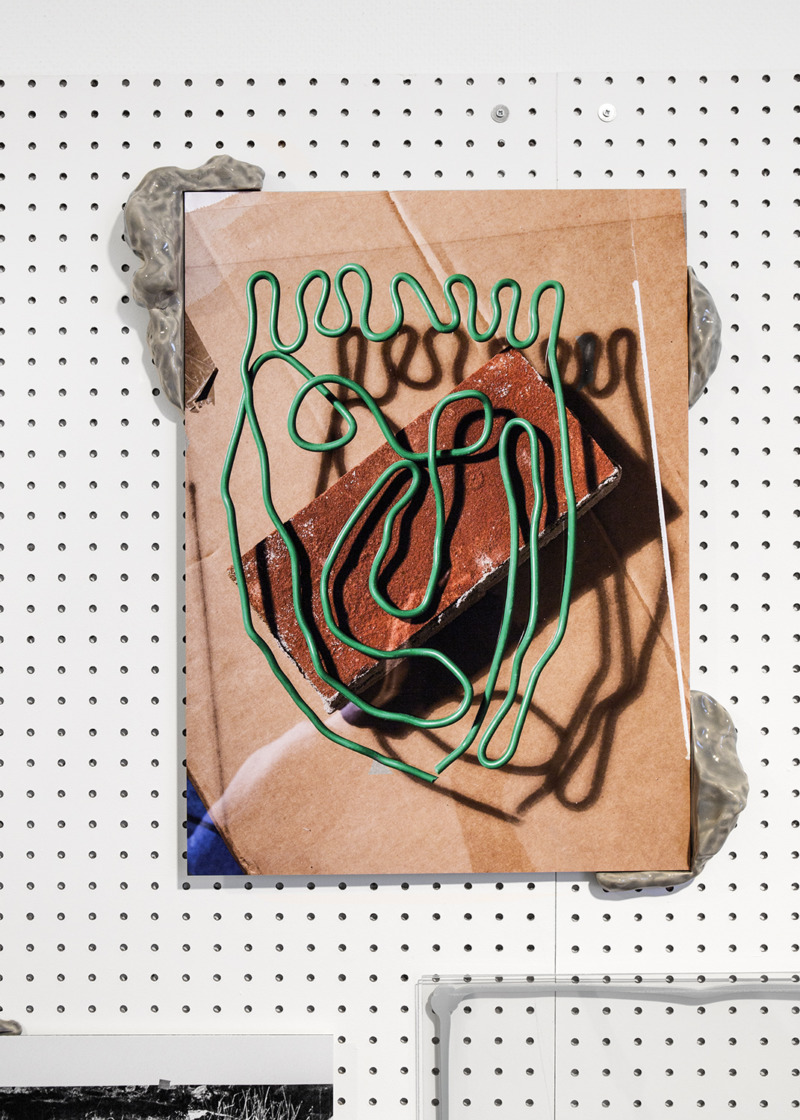

Deflated tennis balls, boiled eggs, azure blue ice cubes and warped pine green metal wires are just some of the materials that feature in Vytautas Kumza’s photographs. The Lithuanian-born, Amsterdam based artist swears by a laborious methodology. Scouring the assorted wares on sale of flea markets sellers, hardware stores and souvenir shops, he plans meticulously how each piece of his assorted bric-a-brac should fit into his expertly-designed images. Threading the fine line between trompe l’oeil and fine art photography, Kumza creates deceitful constructions that provoke and perplex; piles of pebble stones on a bright blue seashore, faces half-covered in a gossamer-thin plastic.

While his earlier works focused on spatial constructions – often incorporating elements of interior design – the 2019 Half empty half full marks a departure towards sculpture-oriented, three-dimensional works that challenge conventional art installation practices.

Could you describe the labour going into each piece? Do you work to a timeline, or is it a more spontaneous process?

For me it’s a very obsessive thing, I look for the right setting for objects by trying to activate them. With objects treated like people and people regarded as objects, the subjects in the photographs are approached with an obsessiveness that forces them to reveal their cards.

I constantly search for different materials that have the potential to perform for me in front of the camera. I collect different items from do-it-yourself, hardware, second hand and souvenir shops. I re-use some of them in my images, I like their metamorphosis, that they make the viewer feel as though they might have seen them somewhere else before.

While the thinking and collecting takes place constantly, the photography part is more scheduled. By then I’ll already have drawn up some sketches, to outline what kind of photographs I need for my displays.

What was the oddest object you considered using, the strangest invention you created?

I guess it was working with fire. Small doses of adrenaline, danger and not knowing how to control it, as well as the surprise of seeing images on the screen. I wanted to photograph a flame for my latest work We won’t fade into, which highlights the banality of commercial photography. I covered the paper background with inflammable fluid, threw a match onto it and ran to press the button on the camera while the flame of the fire was getting smaller. I’m surprised the smoke alarm didn’t go off.

In a 2017 article by Skandl, Nicholas Burman notes that you aim to avoid post-processing all together. Does this still apply? How many of your assemblages are created manually? And how do you know if a piece is finished?

Yes, I don’t use post-processing in my work and am not planning on using it in the future. I’m interested in constructing illusions, spatial constructs in the studio and have them exist only for the time of being photographed. I make noticeable mistakes indicating how they’re handmade.

We live an era when most photographs we see are manipulated. For me, it’s more interesting to make visual constructions that are altered deliberately. I’m placing a variety of obstacles in front of the viewer’s gaze to obscure, twist and blur the objects in the background. I feel that the image is finished when it tells the viewer, “Look. Yes, look again, and longer this time.” I want to invite the audience to decipher their meaning.

You capture the raw materiality of quotidian objects – green wires on a sandpaper-covered brick, a photograph of a soft hand juxtaposed with a windowpane – how do sculptural practices feed into your work? Can it be said that you use images as building blocks for larger-scale assemblages?

My pieces are classified as photography but they are constructed as an installation. I aim to create embodied experiences with the use of sculptural elements and presentation displays. The installations serve as an unfaithful encyclopedia or archive where the display shapes the photographs. My aim is to show how they were produced, and the references feeding into them. My installations operate as a vocabulary, as a collection of tricks. By using visual illusions, spatial constructs, inverted colours and exaggerated scales I try to re-constitute otherwise mundane and familiar objects. Within my displays, I arrange the images to highlight similarities between genres, and to point to structural parallels between outside and inside, organic and inanimate, natural and artificial.

We live an era when most photographs we see are manipulated. For me, it’s more interesting to make visual constructions that are altered deliberately. I’m placing a variety of obstacles in front of the viewer’s gaze to obscure, twist and blur the objects in the background.

On your website, you label some of your past shows as ‘photography based installation,’ and others as ‘series of photographs’. Have you settled on a label for your work yet, or would that contradict the aims of your artistic practice?

My artistic practice developed in a trans-disciplinary manner, combining my background in applied photography with my professional experience as a fashion photography assistant. During my studies at the Gerrit Rietveld Academie, my interests shifted from commercial photography to fine art. I believe this categorisation (on my website) helped me to realise that photography for me is not a single act, but more of a chain of decisions starting with the original idea and ending with the form of presentation, often exposing the craftsmanship behind each image. I started to treat photography more as installation rather than flat images displayed on a white wall.

How did you develop your style? What’s in your research folders at the moment?

I believe that my signature style is a clash of different styles and mixing different contexts. I merge aesthetics and lighting from commercial photography with backstage snapshots of my studio. I like to think of these as the documentation of the unusual processes unfolding within the studio space, as evidence of obscure experiments pushing the laws of physics and aesthetics.

I just gave a lecture at NIDA, a photography symposium that invites trans-disciplinary practitioners, encouraging discussions to take place between different generations of photographers. NIDA offered great opportunity to dig into the archives and get to know about long-forgotten artists. I was introduced to the work of artists pioneering staged photography–going against the humanistic approach prevailing in Lithuania in the ’70s and ’80s. At the moment, I’m very enthusiastic about the work of Violeta Bubelytė and Algirdas Šeskus. The latter was a camera man working at the Lithuanian National Radio and Television. Classified as an amateur, his works were only re-discovered at Documenta 14 in 2017.

I also collect vintage photography magazines. I like images made with strange camera angles, weird lighting, or in an obscure studio setting. They are very different to the works created today. I use this archive/library of tricks as the main source of inspiration.

Craftsmanship is becoming more and more relevant in contemporary discourses, especially in times where everything is digitised. For me, it marks a departure from the mass-production of photography.

In a post series published by Der Greif you named Tom Sachs, Bernard Voïta and Robert Cumming as your favourite artists. Have you always been interested in formalism, in exploring the material qualities of photography? Would you see your practice evolve further towards mixed-media installations in the upcoming years, or do you intend to further explore the restrictions inherent in communicating complex artistic visions via photography?

I only took up an interest in the material qualities of photography in the past few years. I want the presentation to emphasise the materiality of the original objects, to the point where they turn into sculptures. I see my practice slowly move towards mixed-media installations, with a strong base in photography.

I notice that Half empty half full had an elaborately-designed installation style–with some pictures shown on a piece of slightly-tilted, wooden pane, and others against a dotted, white background. You also used a chewing-gum-like, grey material to complement the framing, while some of the pictures were covered with a glass pane. Is this a method you will further develop in the future?

I’m more and more interested in developing my own framing and presentation displays. I feel that it’s easier to reclaim spaces with displays that don’t follow the conventions. In a white cube space, we’re too often presented with flat prints on a wall. I like using display systems or custom-made parts to give context to the works.

For Half empty half full I wanted to explore the role a studio plays in an artistic practice. Shown inside a white cube space, I installed my work station into the public realm of a museum. I used perforated wooden wall panels as the background to display the photographs on, and placed a window in the middle of a space. The resulting installation was like a toolbox of an artist’s trickery. I also used chewing gum-like grey corners to show some works, sealing others between two sheets of glass with silicone, to emphasise the three-dimensional nature of the works.

Where do you see the role of craft in contemporary practice? Do you regard photographers as artisans or artists?

Craftsmanship is becoming more and more relevant in contemporary discourses, especially in times where everything is digitised. For me, it marks a departure from the mass-production of photography. I prefer to customise works, adapting them for the space in which they’re shown. It also allows me to reflect on artistic labour, inviting viewers to re-consider how art objects are made.

What are you working on at the moment?

At the moment I’m experimenting with new ways of presenting photography, making handmade custom clay pieces to hold my images. I’m trying to find other unconventional ways to make photography more spatial without going too far from its roots. I’m also developing some “noise” on the display screens, which I think will give even more depth to my spatial constructions. I believe you’ll be able to see my results soon.