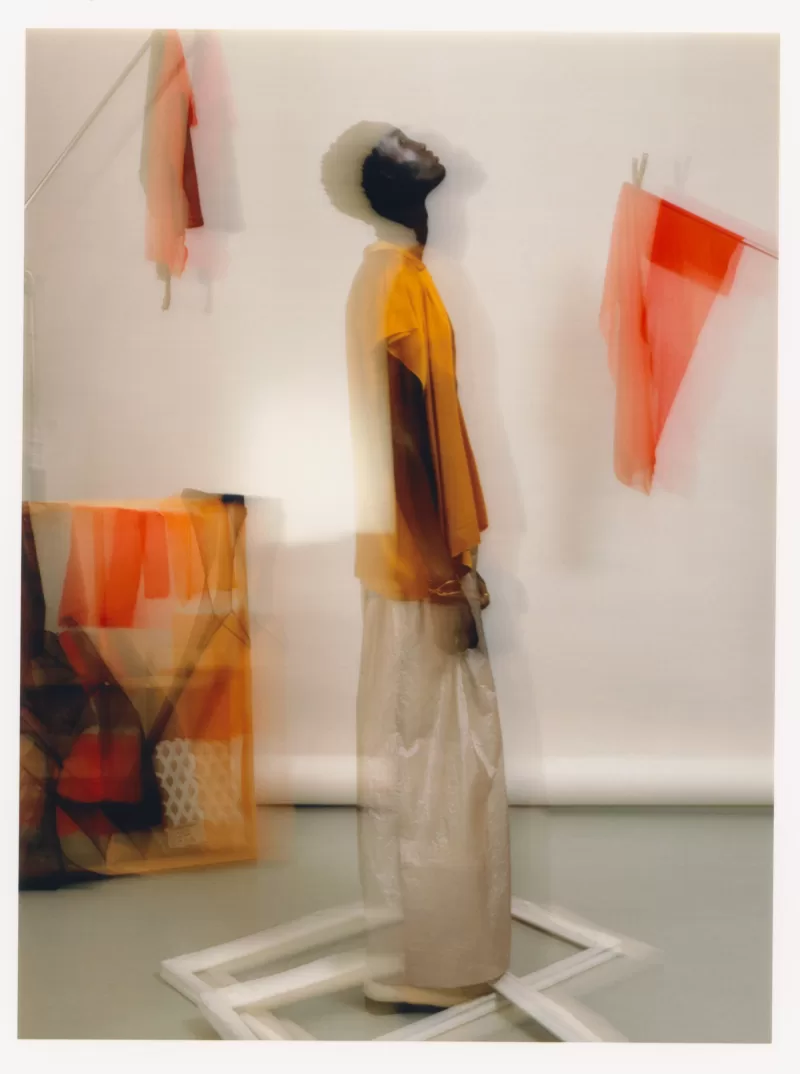

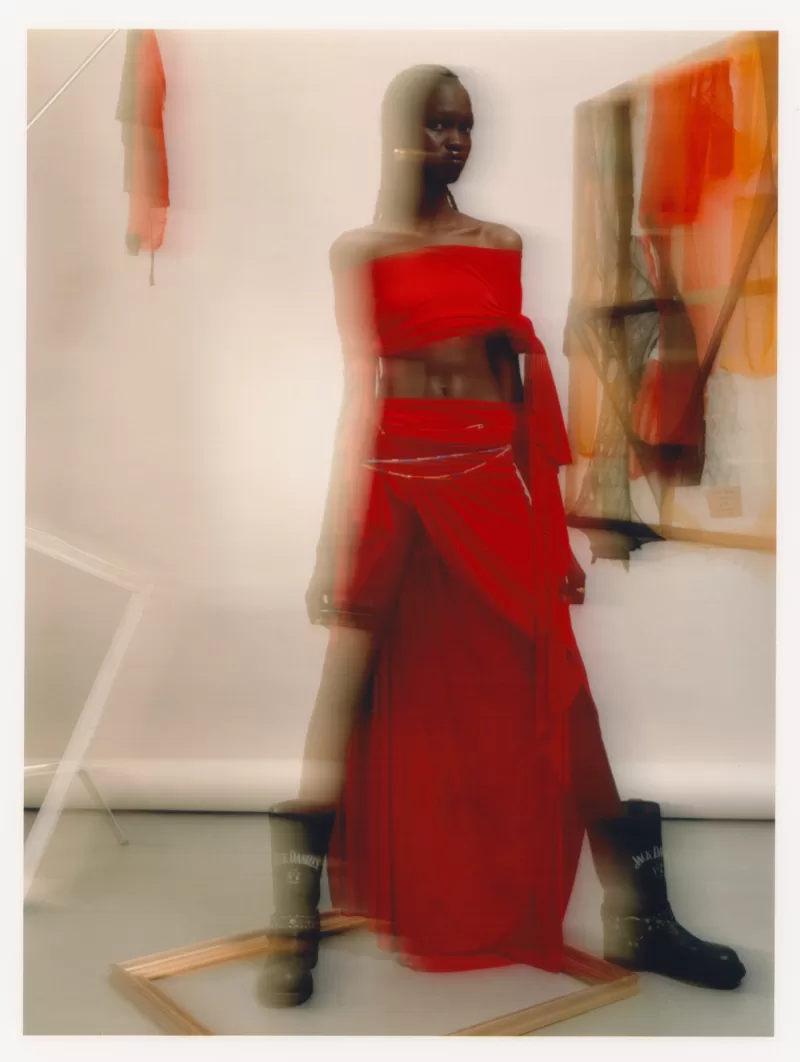

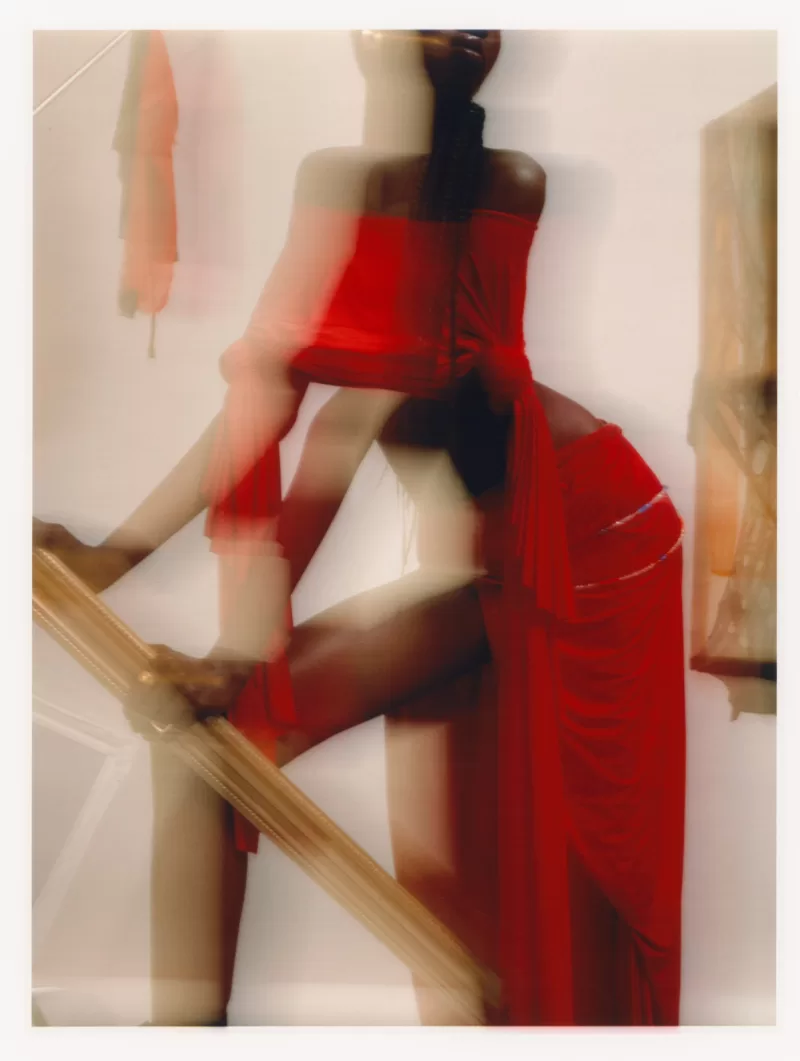

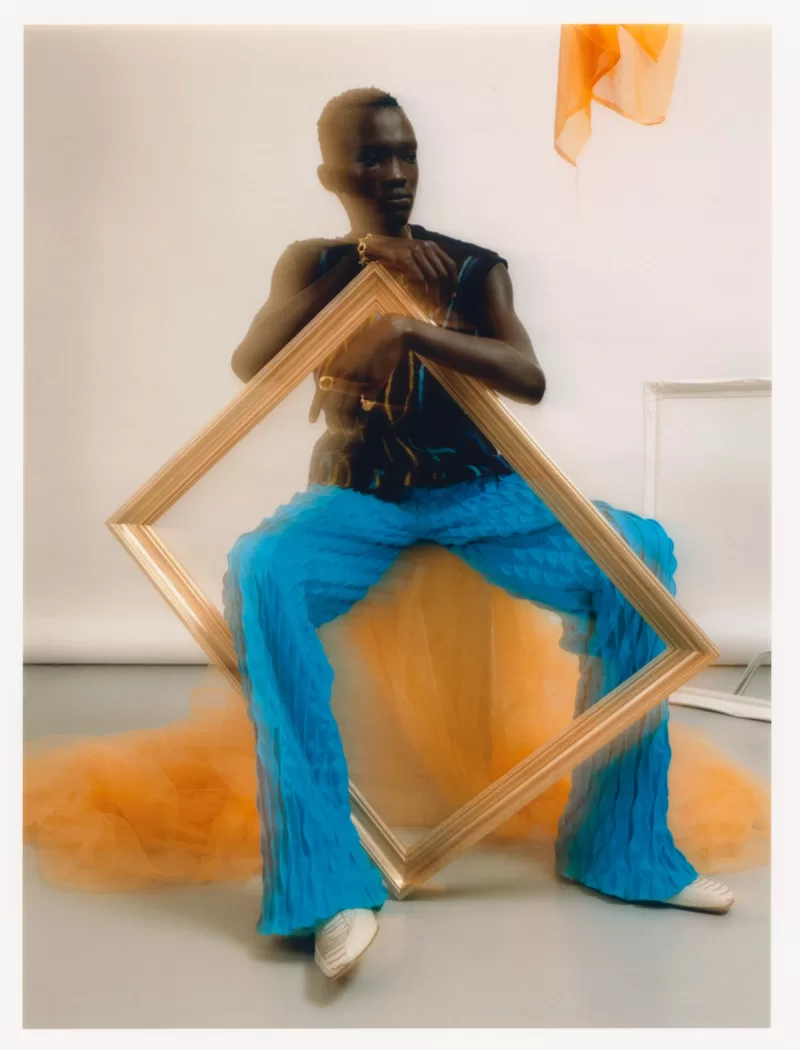

London Fashion Week SS22 – Ones to Watch

The events of the last few years have inspired a quietly turbulent reinvention in many of us. As we begin to return to our normal routines, the conversation about the many ways in which this period has affected us continues to evolve. Creatives are highly skilled at shape shifting in response to a cultural moment but what does that look like within an industry grappling with re-imaging its structures for much needed change?

For many brands and institutions this will be a return to the tried and tested but a new generation of designers are approaching their work in ways that feel less structured, embracing different genres, new technologies and delving into personal narratives to inform their design process.

The late designer Virgil Abloh left an insurmountable legacy within the fashion industry, that of the polymath on steroids. His approach to creativity has had a far reaching impact, giving freedom to a new kind of artist seeking to push the boundaries of fashion which feels relevant to this new era.

In the lead up to London Fashion Week SS22, Paper Journal highlights three designers we feel are exploring some of these practices Marie Lueder, Jawara Alleyne and Feben Vemmenby. They discuss their inspirations and the ideas that inspire their work.

Lueder

You have a background in bespoke tailoring. What made you want to initially pursue this specific field in design?

I imagined an apprenticeship to be the best preparation for stepping into design, especially coming from a family with an academic background. I wanted to learn the craft and everything about it in the best way possible, so I applied to the Hamburg State Opera. It was very difficult to get a spot there, but as I am very patient and love the art of making, touching, fibre chemistry and the theatre, I managed to get through the three years of intensive training.

How has your experience in tailoring influenced the way you choose to design clothing?

When I was making trousers and suit jackets for three years, I really studied the engineering of the garment in-depth and how it transforms from 2D to 3D to become a second skin, which then supports performance and confidence.

I wanted to explore my future wearer’s desire; to find out what they really want by listening and developing a fictional reality for them, understanding and starting again, not knowing where my journey would lead me to.

I love engineering my ready-to-wear garments through this journey with the focus to support the wearer, who should feel hugged and supported. I like to avoid any unnecessary volume of fabric and do a mix of flat pattern-making and draping for my patterns.

Creating an intimate relationship with your customers and offering a more sensitive, tailor-made design experience to them is something that seems to be central in your design practice. Where does this interest in pursuing this more intentional approach stem from?

Seeing as both my parents are care workers, I grew up with the desire to nurture and care for, which gives me meaning in creating.

How important do you believe fostering that relationship between the customer and the designer will be going forward in the future of fashion?

Very! As the consumers are more and more independent now from the retail system and have a stronger position in the market, they can and should change and impact on the world through their purchase.

You liken your designs to armour – is there a specific type of armour that inspires you the most?

I love medieval armour from all nations, those of insects as well as the mental armour people develop to survive everyday life.

Your June 2020 collection was a product of a collaboration with your models to customise and up-cycle pieces they already owned. What gave you the idea to take this creative direction for this collection?

I was missing my friends and peers and was trying to find a way to hang, think, dream and connect with them again. David, a friend and collaborator (who also then participated in the video) and I had catch ups on zoom or FaceTime where we styled feathers in our hair to look like Steve Taylor from Aerosmith, and he was also hand-stitching beautiful arm-warmers out of old skirts. I thought maybe he’d have some clothes he didn’t like anymore and that’s how it started; my budget for that project was £100.

The coronavirus pandemic served as a reset button, an opportunity to slow down, look around and be more mindful, whether that be through our consumption or how we choose to spend our time. How do you think the pandemic impacted your approach to design, especially as a budding brand at the time?

It made me use mainly what was already there and work with pre- consumer waste, dead-stock and to sample mainly in CLO-3D. So, it mostly slowed down consumption while still maintaining to craft newness somehow, and trying to be mindful with myself and my mental health. I still wanted to create shows as we were all anxious, bored and a bit lost at times. The focus in these shows was on trust and safety, and within that taking risks by entering a new territory or journey.

Your recent SS22 fashion film, gafa, was a way to blend your considerate approach to design with technology, which is often fast-paced. How do you see the two informing each other going forward?

The SS22 collection felt like a fictional-reality film where we used the city as a prop. The effects were actually quite IRL as we used green screen fabric and then added more footage into it in the post-production. This rapid set design idea by Tom Schneider was amazing and supported our idea of a surreal heist movie in the city of London, where the abstraction was just the reality of today. I wanted to display the mad times we are in and the electricity you can sometimes feel when not knowing what’s next. Milo, the director, captured that amazingly with his interesting way of blurring the digital and the real.

Otherwise, I work with my friend Holly on creatives for digital styling and a new collection, and like to be able to test the digital for its ability to create intimacy and emotions – not just convenience.

Would you like to continue pursuing fashion films? What is it about the medium that interests you?

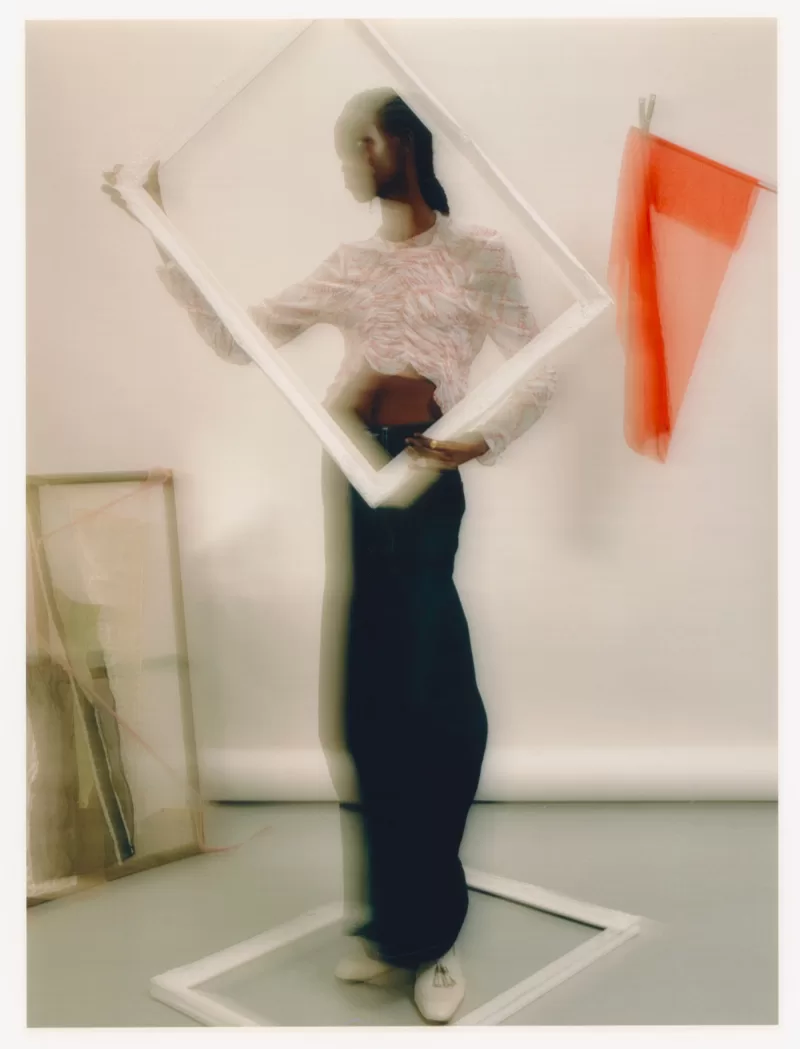

I like movement, and prefer to take a still from a video and use the ghost of a movement which is captured there. I have loved making films since high school and will always make them, to understand the world surrounding me and to press repeat.

Who is the Lueder man? What qualities does he have that inspire you?

I like thinking of masculinities. I can also feel masculine sometimes, and want to support a space where masculinity can feel vulnerable and we have the freedom to desire going on a journey which is unknown to us. I want to design the garments for that.

Getting remnant pieces of fabric from other designers to create your AW21 collection required a collective effort. Is there anyone specific you would like to collaborate with in the future?

I would like to collaborate with someone whom I find obscure, maybe even dangerous somehow in their madness; definitely Alejandro Jodorowsky, as well as a company who produces very specific technical materials for outdoor sports, for example, or a huge supplier for uniforms for amusement parks – I like entertainment.

Jawara Alleyne

You are not only a fashion designer, but also pursue other creative projects such as creating the Art Through Fashion Summer Programme and Art Residency for youths in the Cayman Islands, as well as being the co-founder of Nii modeling agency. Can you tell us a little more about these projects and how they all interact?

While I do fashion, I actually have a range of interests that drive me, as my background is not one-dimensional. My practice is rooted in design, but it took a long journey of doing a lot of other things to get to this. I always knew I wanted to do fashion – but the journey to launching my own brand and designing under my own name wasn’t a straight shot.

I grew up in Jamaica and the Cayman Islands. I was extremely diligent and driven, but it’s not easy being a creative kid in the Caribbean. I was continuously asked by society to not be me, to not do what I was clearly meant to do. The summer program is my way of giving back to the community by showing them that creativity isn’t a job. It’s an approach to life that enriches whatever you do, and needs to be nurtured and valued. I also really believe in sharing knowledge through collaborations and discourse, and I’ve learned a lot by having to be pushed into so many different situations.

Though all the projects I do might seem separate, I think that all have some lines of intersection as my research itself has a number of different stories that run alongside each other to inform and enrich the brand’s point of view. My interest in fashion really starts with people. I love anthropology and sociology and am fascinated with how people make the decisions they do. With this being my entry point into fashion and identity, it allows for conversations that can meander but always come back to our humanity playing out on the stages in front of us.

You initially went into womenswear at London College of Fashion, only to decide to switch over to menswear in your final year. What ideas influenced this change?

I actually have been doing fashion since I was a kid and did my first show at 16 in the Cayman Islands, but I always did womenswear because I started my interest in fashion by imagining my mother and drawing her. I think I came to London not only to learn more about the industry and about design, but also about myself. By the time I got to my final year of BA, I realised that I’d done what I needed to do in womenswear. On one hand, I lost interest; but really, I think after years of studying the female form I realised that that discourse at the time was not mine. I’m very introspective and reflective in the way that I work and I have a strong connection with my work – approaching it more like art rather than fashion. I came to the realisation that I don’t have a female form and I was actually quite removed from that discourse. At that point menswear was far more interesting because not only were there more boundaries to be pushed, but also, realistically, I actually had a stake in the game of redefining what contemporary menswear looked like because it’s something I could actually feel.

Being a black queer man growing up in the Caribbean, there was so much about my identity that hadn’t been discussed, so many things that we weren’t allowed to say, and I realised that through fashion I could delve a little deeper into what it meant to be me. I realised that I had no new perspective to offer to women, but also the choice to change was really a chance to reflect on my own identity and find the answers to some questions that I knew I was not the only one asking.

Does the Jawara Alleyne man have any characteristics that were found in the Jawara Alleyne woman? Do they cross over in any way, and do you see parts of yourself in them?

The Jawara Alleyne man and woman are opposing sides of the same coin, the faces changing with each flip. When I was a child I grew up in a really large family and further a community of men who weren’t afraid to show and share their feelings. Their sensitivity was so strong. On the other hand, the women around me were hardwired to be tough. They were like these Amazons who had to be in order to face the harshness of Jamaican society. I think the Jawara Alleyne man and woman equally represent parts of our masculinity and femininity that we’ve been told to hide, but now we know that we’re all sliding up and down the scale of the divine masculine and feminine. Re-centring and rebalancing in a way that allows for the presentation of a man that’s sensual and a woman that’s hardcore, but in a way that presents reality as it is – the men and women that we know exist, rather than sensationalising what the masculine and feminine could be.

How have your experiences growing up between Jamaica and the Cayman Islands influenced your views on masculinity?

Growing up in a family of a lot of strong women and men who were not afraid to show both their strength and their sensitivity, I think from a very young age I had this feeling that masculinity was not defined by your gender or sexuality. Growing up within a community of men who were all so different and filled with character was quite inspiring for me as that showed me how everyone’s expression of their sense of masculinity is so different.

I do, however, come from the place that basically put homophobia on the map – and we can’t skip over that fact – but being able to balance that experience alongside The Cayman Islands, which is also conservative but in different ways, showed me how subjective identity is and how the lives we end up living sometimes become a matter of perspectives imposed on you.

I think these experiences broadened my understanding of masculinity because I could see my reality not solely from my experience: I not only had people around me who also expressed their senses of masculinity in different ways, but I also had two different societies that enriched that understanding as well.

How have these experiences allowed you to explore and redefine the way you choose to express your own personal masculinity?

There’s a certain sense of just being myself that I can’t run away from. The older I get and the more I grapple with the concepts of what it means to be masculine, I keep coming back to the fact that we all have to be and express how we feel. Growing up in the Caribbean forced me to hide my sensuality and femininity, and as such when I moved to London I rejected my masculinity because it had been a place that I was forced to hide in. I think now I’ve learned to accept both sides of myself, and not to reject parts of myself that make me complete.

How has this played into your designs?

I don’t necessarily design for myself. However, having studied masculinity through the way we dress and broken this down over the years within my personal research, it’s allowed me to approach design for today’s man from a bit more of an honest point of view – not one that fetishises either side of ourselves, but instead focusing on presenting the reality of the complexity that each of us as individuals share.

You’ve mentioned in the past that Caribbean mythology is a prominent source of inspiration for your work. What particular aspects of these myths do you find yourself pulling from most?

Mythologies themselves come with a sense of mysticism and magic. What inspires me most about Caribbean mythologies is how they allowed me to dream. I was pulling elements from our (Caribbean) stories to paint a better picture for the Caribbean world I wanted to see, but not necessarily the one I grew up in. It’s the access to dreams, really, because in many ways we’re not allowed to dream. Creativity is looked down upon but it’s something that our society is built upon.

Caribbean mythologies are often passed down through oral culture, which makes the approach a lot more about feeling the stories rather than pinpointing the exact aspects that might have led to anything being anything.

Many of the pieces in your AW21 collection have elements of upcycling – why did you choose to take this approach when creating the clothes?

Growing up in the Caribbean, this approach to using, reusing, upcycling, revaluing, and repurposing objects has always existed across many different facets of (Caribbean?) society. It’s ingrained in the way we think about objects and life as objects take on a circular life. I didn’t choose to do up-cycling really, it just made sense. I always say that I’m not a sustainable designer, but I am a designer that thinks consciously about my approach to design, and to me this discourse of value has always made sense because that approach reflects my everyday.

You launched your debut collection during lockdown. What was that like for you? Has the pandemic changed the way you approach design?

That was a roller-coaster. I moved to London from the Caribbean to study fashion, and after years of being here I finally graduated from my MA right before lockdown. I was filled with so much passion and drive, and I had to direct that somewhere, so I didn’t stop. I kept myself busy over lockdown and that led to my debut. I was never the kind of person to sit still and wait for things to come my way, and for me the lockdown only served to enhance that because I was locked away with nothing but myself, and I really just wanted to create.

For me fashion is not a job, it’s an approach to life that gives me a perspective to root my inspirations in. I don’t think the pandemic changed the way that I approach design, but what it has done is affirmed the importance of taking risks within fashion, being bold, stepping out and trusting your gut and just taking the time you need to get better at your own practice. I think it actually has made me a better designer and filled me with even more drive.

In what direction do you see menswear heading into? Do you believe a constant redefinition of what’s considered masculine is the way forward?

We think we have to redefine masculinity but we don’t. Different types of men have always existed, it’s just that we rarely show these men as archetypes of masculinity and beauty. Our standards of what is considered masculine is quite rigid, despite meeting men everyday who don’t subscribe to that. I do think this is sad because it creates this identity crisis that men seem to have of not understanding how to be themselves, (because the examples of what’s masculine is so rigid?). I don’t think redefining masculinity is necessarily the way forward, but highlighting the different types of men that exist is. We’ve just come through an age of diversity in fashion, but diversity and representation doesn’t stop at the colour of your skin.

Your last collection was a continuation of your MA graduate collection entitled The Self-Made Man. What does the self-made man represent to you?

To me, the self-made-man of today is someone who has defined masculinity for themselves and lives within their truth – outside of what the world tells them to be.

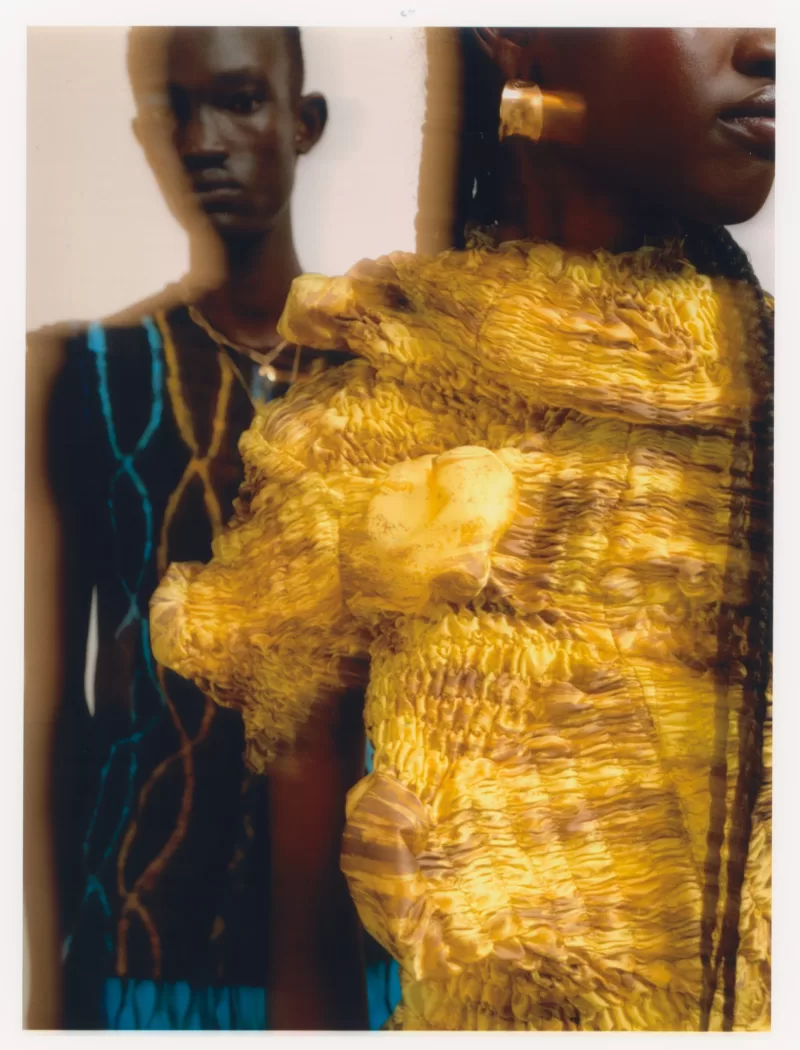

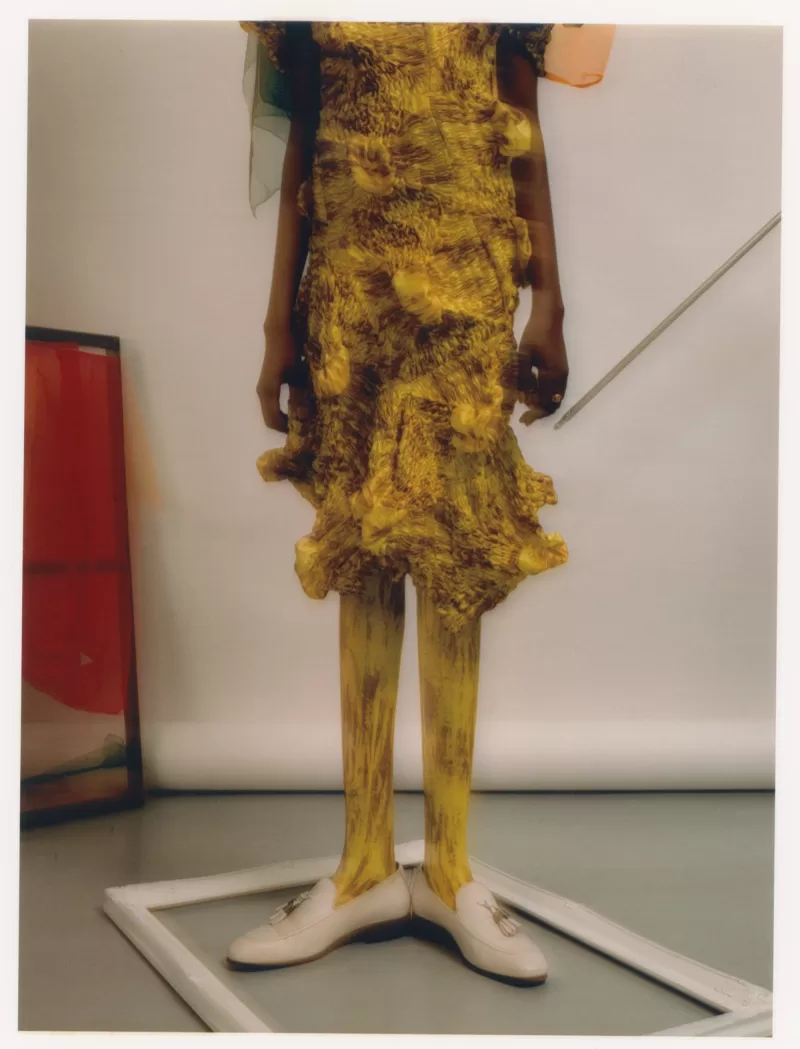

Feben

There is a strong commitment to amplifying black women through your work, including your mum who’s image has appeared on one of your bag designs. What are the qualities you find most inspiring about the women you’ve chosen to highlight within your collections?

I find strength and a personal language really inspiring, specifically strength by being raw and authentic. Anyone with a strong sense of self and character is a huge source of inspiration for me.

With this season’s collection you’re showcasing menswear for the first time. How does the process of designing menswear feature in your autobiographical process?

I don’t think my work is defined by gender to be honest. It’s about creating work that is within my vision and whoever would like to wear it.

You seem to be drawing on a wide range of references from Renaissance painting to pop-culture. Can you tell us a bit more about your research process?

My work is my identity: things I have grown up with and cultures I have been exposed to. I usually start from the beginning, like with photo albums. It’s personal, but in the end I want to express my initial mood.

You’ve spoken previously about a common experience of being one of very few people of colour studying on your MA course. What did you learn most from this experience?

I was the only black woman in my class; unfortunately that’s a reality for many people, and something I hope changes soon. It’s hard explaining truths and references to people who come from a different world. It’s important that you believe in yourself in moments like this. I will always value my time on the MA at Central Saint Martins, and am forever grateful for the Isabella Blow Foundation that gave me a scholarship to support my work. The masters gives you an opportunity to develop your work and push it to a different level.

You’ve also talked about how a designer’s work should reflect the times, ideas shared by the artist Nina Simone who featured on one of your dresses in your debut collection ‘It’s Not Right But It’s OK’. Has the lockdown and its constraints changed your approach to design and creativity?

No, but I think and hope it’s given people a bit more perspective on what’s important in life.

It seems that the real change in the industry is coming from emerging talent who seem to be cultivating a more contemplative and holistic approach to design. What do you think emerging brands can teach more established brands to bring about the change we need to see in the industry?

First of all, I think they need to question themselves if they want to be open to change, and take the conversation from there onwards. Putting new people on, real support and not ticking boxes for surface level reasons.

The term surrealist is often used when describing your work. Can you speak a little bit more about that?

I think it’s because of my approach to my work, it becomes surrealistic. The research and personal references I merge often have surrealistic outcomes.

You have spoken about being influenced by the Japanese philosophy wabi sabi. What is it about that philosophy that speaks to you and informs your work?

What I’m drawn to the most with wabi sabi, and what I use from it, is how I re-work fabrics to create 3D textures, by deconstructing them and making them into something new, something imperfect.

Collaboration seems to be something you enjoy and you seem to work across disciplines on different types of projects. Are you able to tell us more about these?

It’s super important to uplift each other whether it’s outside of work or not, to take care of your community. I think anything becomes better when working together; there’s so much we can learn from each other.

What’s next for Feben?

I will be showcasing AW22 with British Fashion Council NEWGEN.

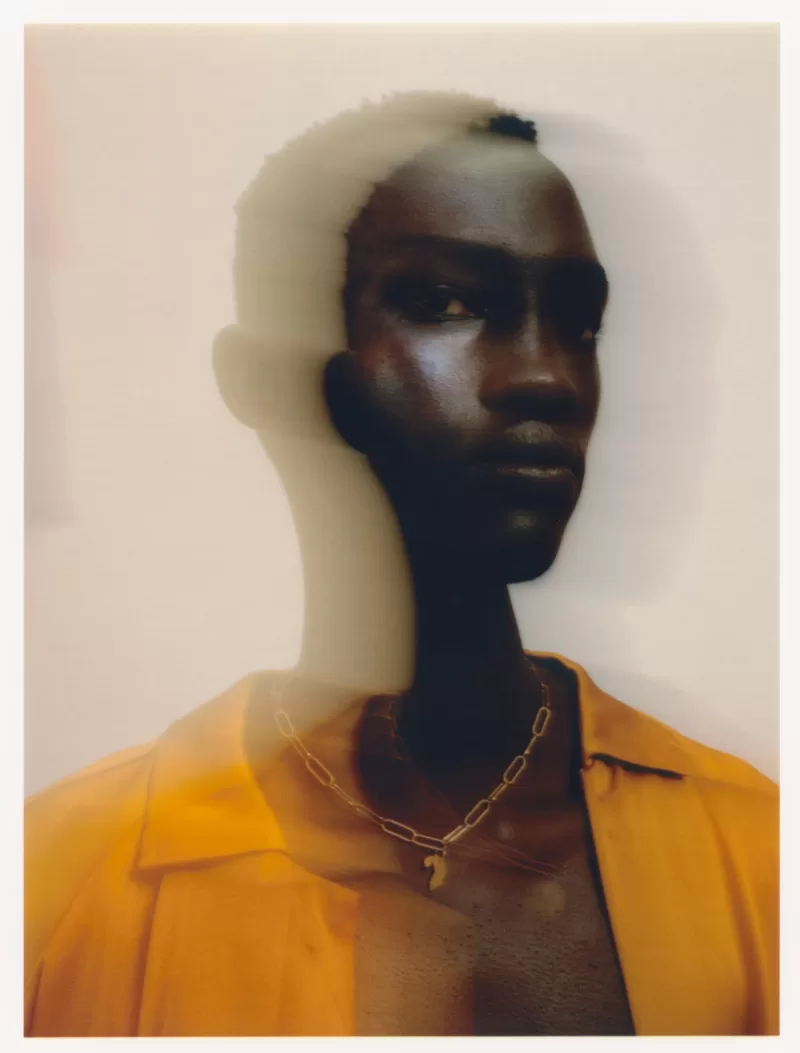

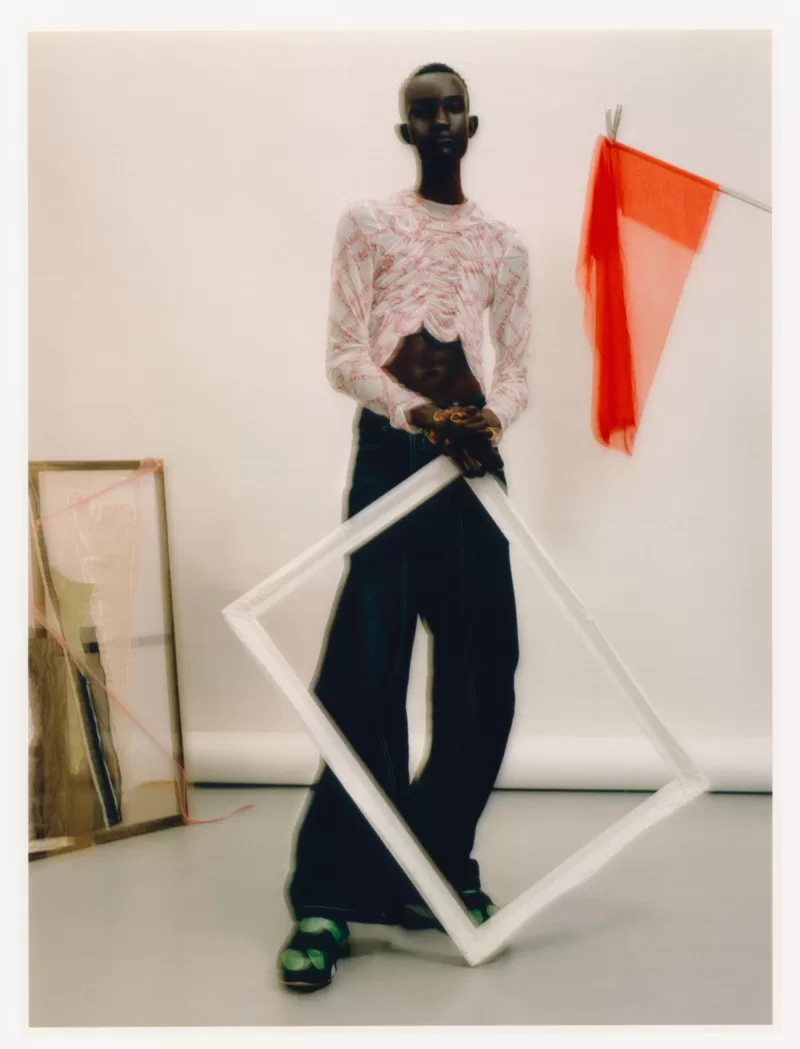

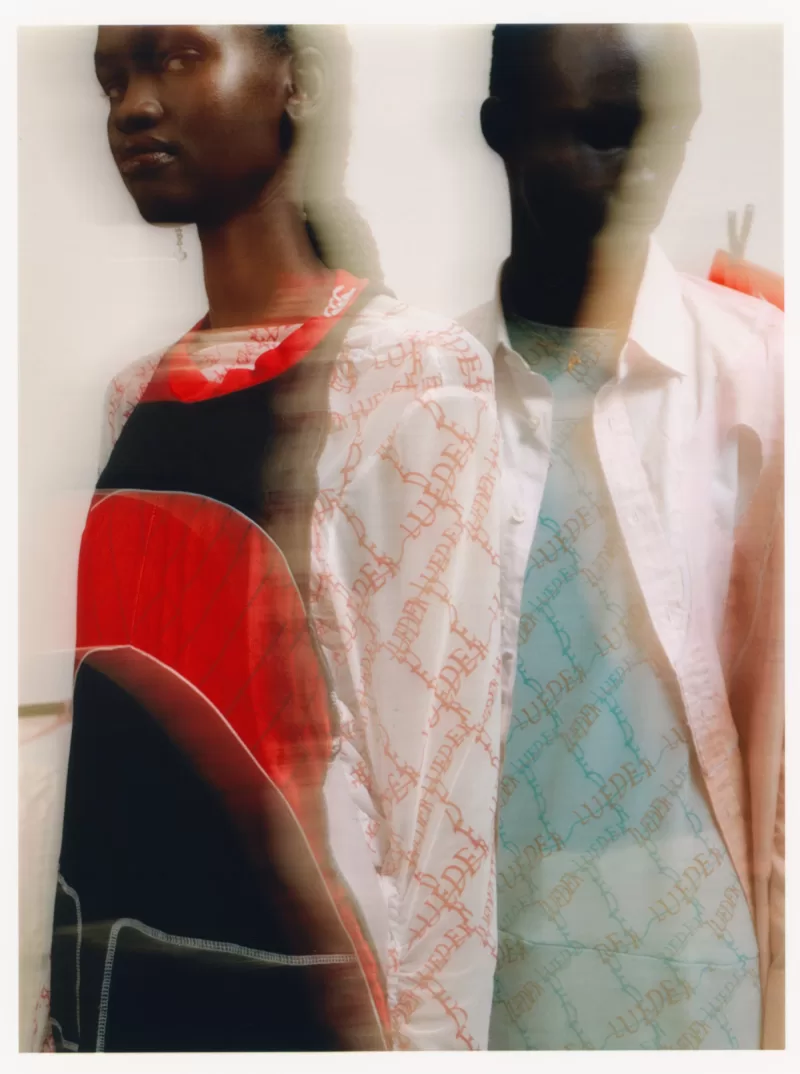

Photographer Kevin Voller

Stylist Shirley Amartey

Make up Emily Dhanjal

Model Diana and Goi @ PRM agency

Special thanks to Jody @ theeyecasting